Talking Back at Movies

Is The Audience What Understands Pictures Best?

Been reading of movie audiences then-and-then by Manny Farber (40’s) and James Harvey (50’s). What is said to have begun in dutiful silence became more and more free-for-alls, verbal exchange between viewership and projected image that could not talk back. Farber says it got worse in the war. Harvey remembered college age "wise-asses" making "jeering expeditions" to movies they did not respect, which by the fifties was pretty near all movies. May we assume Farber and Harvey’s experiences reflected filmgoing as a whole? I spoke to Conrad Lane, who was in theatres from 1933 on. What he saw/heard differed somewhat from their accounts, but then, couldn’t any of us come up with anecdotes unique to individual experience, not shared by these or anyone else that went to movies? Conrad says patronage in better theatres were always well-behaved, a “quality” audience, but also admitted crowds were “progressively unruly” as years went on. There was always child clatter at matinees, Conrad recalling a girl in his party yelling out during a chapter of The Miracle Rider for Tom Mix to “Be Careful!” as he entered a doorway, an outburst he attributed less to the child being disruptive than inability to separate screen fantasy from her own delicate reality.

How did surrounding viewers comport themselves as we sat spellbound through films? My first exposure to sci-fi, if not horror, was Konga in 1961. I went with cousins, maybe a sibling or two. Anyhow there were at least four of us in the group. Being age seven at the time got me into the Liberty for a dime. I was prepared by the posters for an intense exchange, Konga after all a gorilla that grows to unnatural size. What I did not expect was sarcasm among my crew that greeted his arrival on screen. And they expressed it … out loud and for anyone to hear. After a while, I got into the mocking spirit. No monster movie could scare me! A third-act crisis found Konga engulfed in laboratory flames and hurling a player thereto, latter ID’ed as unsympathetic and having it coming. I compared (aloud) Konga’s gesture with roasting of marshmallows and drew laughter from companions all older than me. Resolved then: I had “resisted” the intent of Konga to frighten us, had in fact embraced the raw material of cinema to express my own alternative postwar modernism. Well, that’s at least what academics would tell me. Truth is, I felt like Tootie after she threw flour in Mr. Braukoff’s face, having like her conquered all fears. Afterward I overdid my inclination to rewrite what was said on screens, enough so to be pointedly excluded from neighborhood expedition to see Morgan the Pirate a couple months later. Why attend movies if your goal is to ridicule them? A bunch of us fourth graders were rowdy enough to be nearly thrown out of King Kong vs. Godzilla in autumn 1963, only this time I felt less proud and more a follower behind boys who had not looked so forward to KK vs. G, certainly not enough to paste Winston-Salem Journal ads for the film on their school desktops as I did.

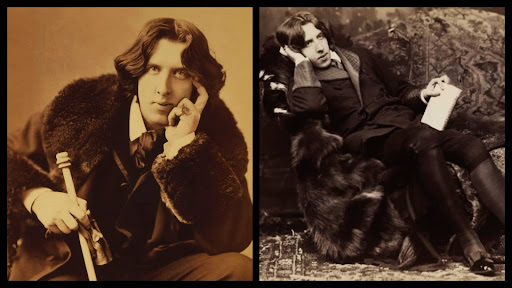

Everybody’s a critic, so it was said, the more so when cult and camp gnawed ways into public consciousness. It was OK, even desirable, for audiences to yap back at films. Truth to Power as it were. Conrad remembers when crowds sat polite and did not interrupt drama's unfolding. Yes, they were restless with Limelight at San Francisco’s United Artists Theatre in 1952, but courteous enough to go the course. Soon, however, it was expected for us to seize the lectern, turn the tables, and bend moviegoing to suit ourselves. The nineteenth century had seen this coming via vaudeville viewers rowdy and demonstrative till management organized to shut them up, a success through applied and organized effort. Writers who came before argued for “creative engagement with text,” Oscar Wilde in 1890 calling his critical work a “starting point for a new creation,” the goal “not to explicate meanings inscribed in a text by the artist, but to record (our) own intensely personal impressions of the work.”

Once a thing of art was finished, it belonged to us to do with as we pleased. Other writers of a late nineteenth century saw change coming. For Thomas Hardy, “intensive power of the reader’s own imagination” would find values in his novels “which … was never inserted by the author, never foreseen, never contemplated.” Wilde and Hardy knew writings, theirs and anybody’s, would land in the lap of gods that were their readership, latter to apply whatever meaning such creations would acquire. What an engaged movie audience did was less personal, them among a crowd after all, so why not share their response with others who might view the thing a same way? Theatres would again be debate societies, only now viewers got the last word, provided no one sitting alongside challenged them. Things could get tense, however. I was at a campus screening (early 2005) of Northwest Passage, a childhood favorite of the instructor who obliged his class to attend. It was a laser disc, thus a bit bleary when projected on a too-large-to-wrestle-pixels screen. The thing played to dead silence for fifteen or so minutes till a lone voice cried THIS SUCKS. From there to the end, another two hours, was march to Calvary.

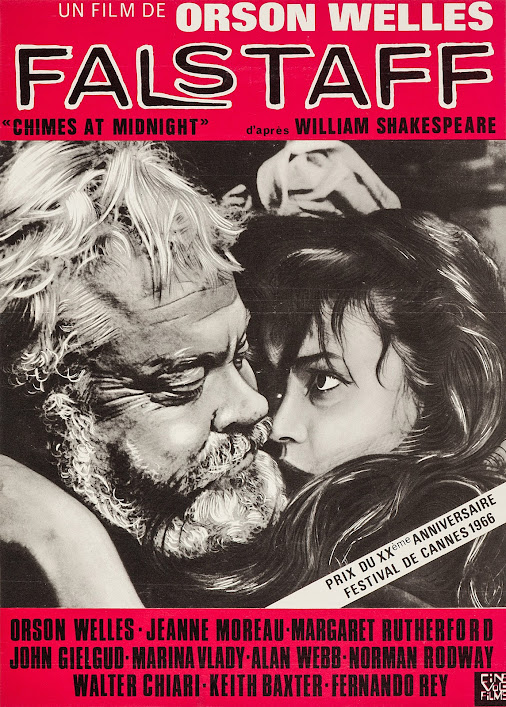

Audiences could be plain mean, especially ones at light side of maturity. Peter Bogdanovich taught filmmaking and cinema history at the North Carolina School of the Arts in Winston-Salem from 2010 to 2015. Less than an hour from me, the trip was worth it to sit in on classes, permission to do so graciously given by UNCSA and Mr. Bogdanovich. Here was opportunity to see/hear the famed director and writer interact with students, after which I'd get to chat with him myself. Classes were held in a theatre/teaching auditorium. Opening hours saw the day’s feature, followed by discussion. I usually showed up near the end of each movie, wanting mainly to hear group reaction and Bogdanovich’s remarks. Size of the room allowed students to spread way out … two here … one over there … three or so far in the back, not unlike theatre going of present day. Bogdanovich regularly had to herd them closer to the table where he sat so they could see and hear one another. None lit up at prospect of Chimes at Midnight or His Girl Friday, carping nearly always when Bogdanovich asked what they thought. One day he had enough, lighting into the bunch for not having anything “constructive” to say, his selections never good enough to suit them. Here was once where the screen (or screener) talked back on no uncertain terms to the audience, Bogdanovich as engaged for that moment as ever I observed him through what must have seemed a career low (though UNCSA is considered a world class school, it’s still 3000 miles from Hollywood).

We’re talking degrees of rudeness. Mine at Konga was no less annoying to whoever sat back of us, unless they were enchanted by snide remarks from a seven-year-old. I'd later grow into rapt attention and lack of patience for ones less considerate. By 1963 and The Haunted Palace, our Liberty was my sanctuary wherein worship of Vincent Price must be conducted in silence. I had gone from boisterous to priggish. Others still sought fun from movies, especially those meant to scare. Ann used to watch Shock Theatre with her brother on Channel 8, Saturday nights. He would boil hot dogs in water that turned a sick pink as they settled into Godzilla vs. The Thing, The Brain That Wouldn’t Die, or Gamera the Invincible. “It was always American-International pictures!” she recalls, as if that were a bad thing. Here then was “text” that invited its consumer to find his/her own meaning, be it regard or disdain. I developed hearty distaste for “camp,” thinking it was mostly peer pressure that caused others to laugh at things I held dear. There was hesitation at sharing favorites with a group. First semester at college saw Channel 36-Charlotte broadcasting the first three Frankensteins on a Friday night. I invited the hall to come in and watch, at least ten showing up, the small room filled. Which way would they tilt? To my delighted surprise, the group sat entranced. All had seen these before and respected them. A moment’s levity came of reaction when Valerie Hobson threw herself across Colin Clive lying prostrate on a bed in The Bride of Frankenstein, one boy's an indelicate observation I’ll not share for propriety’s sake. Suffice to say, the interruption was OK because his remark was really funny.

“Creative criticism” was something I tried applying to reviews wrote in 1968-69 for our local bugler, most Liberty fare too weak to inspire fun-poking. Audience response was minimal because at weekday matinees, there was virtually no audience. This was dawn upon day when small town theatres were going to evening and weekend only policy. After I got done reviewing, new movies held faint fascination. I went but occasional and usually saw cause to regret it. Straw Dogs was a film that might be read a variety of ways by an intelligent audience, but the Liberty's crowd marched out like from Jeffrey Cordova’s Modern Faust in The Bandwagon. Whooping it up at the movies seemed all done by the seventies. Had a moviegoing public been intellectualized into obedient silence? Too much perusal of Pauline Kael perhaps, but then there were “midnight movies” the dump ground for stuff no exhibitor wanted to use during the week. I didn’t go unless they were revivals, and even then, it was hell staying awake in a theatre where The Cocoanuts and Duck Soup didn't let out till 2 AM. Always it returned to a same question: How much did anyone care about movies one way or the other? Sure there was “film culture” in Manhattan, but I never saw much of it down here. Maybe at UNC in Chapel Hill, plus Wake Forest had a terrific program (Doug Lemza in charge), but my little shows, at a little college, played for most part to sparse groups, less there to engage with the movie than satisfy mildest curiosity and pass idle hours. I’d like knowing percentage of my age group that fully embraced films, let alone interacted “creatively” with them.

Do most people simply watch and walk away, better off for doing so? Why strangulate on analysis? I know a man whose job is handywork, in other words practical things. We spoke recently of a Netflix offering, Hell or High Water. “Real good” he said. Then I mentioned a tense scene near the end that Jeff Bridges played with Chris Pine. My guy, who watches films casual-like, made with perspicacity to send Kael begging, were she here to compare screening notes. Point is the people we think are barely seeing films are often seeing them deeper than any basket of connoisseurs, deeper even than folks that made the films. Oscar Wilde and Thomas Hardy knew what they wrote was often received on more sophisticated terms than they dreamed of. How many get beyond a tenth of what a good book or movie offers? Not me, and I really do try. We jabber over what makes a picture great, then some or other listener bats an insight over all heads and proves again that anyone who writes about film or whatever art should stay humble. Just like in any walk of life, no matter how adept you think you are, there is always someone who's better. I get the hint often from comments to Greenbriar, each an alert to dig deeper next time.