Canon Fire #3 (Part Two)

Among the One-Hundred: The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) --- Part Two

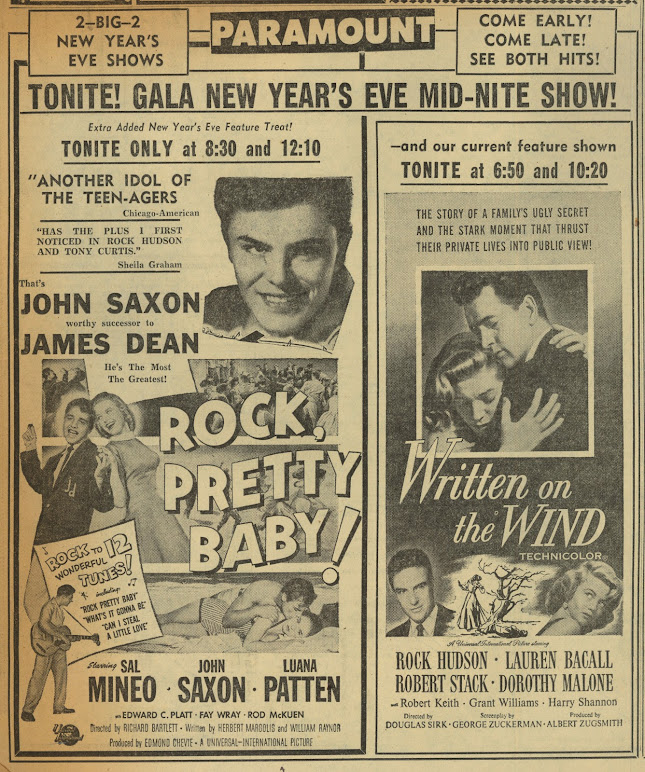

Fred stops by Bullard’s Drug Store, Midway Drugs a chain lately in possession. Too many grab at bargains from overdressed shelves, the war having put money in pockets and ways to waste it. Fred wants no part of this but pays respect to old man Bullard (Erskine Sanford), friend and mentor who has sold out but stays on to fill prescriptions. “Clarence (Sticky) Murkle” who once assisted Fred is now pit boss for Midway but hasn’t grown character, nor tendered war service. Too young? Doesn’t look it, so we assume another slacker or happy-to-be-so 4-F. Clarence observes “Nobody’s job is safe with all these servicemen crowding in,” to an attractive woman who reacts with silent contempt toward this runt presuming to be Fred’s equal. In fact, most of women and girls at Bullard’s/Midway stare after Fred with frank appreciation, there still being nothing like a man in uniform. Rat-faced store manager “Thorpe” (Howland Chamberlain) makes plain right away that Midway is under no legal obligation to give Fred back his job, but should they do so, the pay would be $32.50 a week. Thorpe is snide, dismissive, another who resents men like Fred who under proper circumstance would be his master. Little moments of humiliation are where The Best Years of Our Lives best captures reality of return to civilian life. So many soldiers were suddenly back, with too few jobs to distribute among them, Fred’s dilemma not unlike what Cagney’s “Eddie Bartlett” in The Roaring Twenties experienced home from trenches, seeking his old garage spot and being told they can no longer use him.

Al is wanted at the “Cornbelt Trust Company,” former boss “Mr. Milton” (Ray Collins), whom Al never calls by any other name, bearing gift of a personalized briefcase and big raise to commemorate Al’s return. Mr. Milton’s anxiety to have latter back on the job is almost unseemly, Al’s increased value based to degree on war service that depositors know about and trust Cornbelt the more for having this veteran among firm assets. Al will earn good, in fact better, money, his family secure in a lavish apartment, but he’ll also stay beneath Mr. Milton, the older man’s intentions good if unctuous toward a returned warrior he regards like a “younger brother.” We know Al saw frequent combat. He didn’t come by the sword and Japanese flag in a crap game. Al even warns Fred at one point that he knows plenty of tricks and how to “fight dirty.” Fredric March was forty-nine when The Best Years of Our Lives was released and looks it. We could wonder why Al never got past sergeant stripes as he seems like officer material. In fact, he could have sat this war out altogether and suffered no reprisal, same as March himself did. Latter had served as an artillery lieutenant in the first war (and interestingly, began his post-WWI career as a banker). Al has least of issues rehabilitating, being mature and a seasoned family man, but we worry about his drinking to excess and wonder if Milly might have increased problems over that, Myrna Loy well cast given such circumstance. Best Years could be the Nora Charles story followed to point where Nick’s indulge must be seriously addressed. Would veteran services at the time have offered rehab options?

Homer’s drama is unsettling enough as to see less of him than Al and Fred. Permanent handicap or disability touched family or at least acquaintance of so many that saw The Best Years of Our Lives during 1946-47, none complacent after this conflict. Homer is damaged to where he wants to be left alone, us to wonder if marriage to Wilma will really help. Any happy ending for Homer will be qualified, for unlike Al or Fred, his handicap won’t be fixed. I say Al and Fred, but who can assure Fred’s nightmares would go away, or that Al’s problem drinking will abate? Ritual of Homer undressing for bed is done on quietly realistic and understated terms. When Dad helps, we see Homer close up, mechanics of harness and hooks withheld for greater impact when Wilma later assists, this the moment where the couple will bond, and Homer resolves finally to marry Wilma. Their going upstairs to Homer’s bedroom was among most intimate moments between two plain people that anyone watching might identify with. Here we see Homer for a first and only time without hands, no hardware to soften impact. A “shock” for audiences seeing such limitation on graphic terms, this was a talked-about, if not most talked-about, segment in The Best Years of Our Lives, fairly aching with emotion, a must-see moment in truest sense of the hackneyed term, and recognition of new maturity for films now that war was done. The Best Years of Our Lives signaled movies to grow up in accord with expectation even of youngest people who thanks to a last four years understood wrinkles in life Hollywood had by policy ducked, but now was obliged to confront more directly.

Fred’s marriage goes awry as expected, Marie offering no sympathy for his running out of combat cash and bent now to workaday grind. She also keeps their apartment like a rathole. Marie is every loused-up thing Peggy is not. We may safely assume she came of rough beginnings, but so undoubtedly did “Hortense,” married to Fred’s done-in and alcoholic father, but Hortense is kindly, her background Best Years proof that books need not be judged by covers. Fred will fall for Peggy as she has with him. Their attraction is as credible as it is intense, what splendid writing and direction achieve where each come together. Peggy admits to her parents that she wants Fred and will fight to have him. To her lights, Al and Milly don’t understand what it is to know such passion, cue for Best Years speech many would cleave to in moments where marital commitment was under siege. Milly relates times, many, where she no longer cared for her husband and believed it in her heart, that they had to fall in love all over ... and over ... again. Pins dropping, or popcorn kernels touching floors were heard during this I bet, audience couples pondering if they'd give their relationship one more try, to fall in love “all over again.” Were it possible for movies to have constructive outcome for viewership, here was it, but then The Best Years of Our Lives is filled with such nuggets as this.

Could anything like a boss or co-worker frighten men like Al or Fred after what war dealt them? Al approves a loan to farmer “Novak,” the man's character sufficient collateral. Sourpuss toady “Prew” (Charles Halton) reports this to Mr. Milton and Al is called on Cornbelt carpet. He’ll not come off his judgment however, sooner the job be chucked than bend to bank will on this occasion. Same with Fred at the drug store. Being close to life-death wall left Fred-Al aware that “danger” perceived in working life amounts to none by comparison. Did this make stands upon principle more common among their generation? Did fighting men come from respective brinks determined to live on their own terms? I grew up among authority figures who shrank not from pressures their offspring cowered before. So many seemingly bigger than life men were what peers and I imagined to be permanent fixtures, except they sadly were not. Once gone, there really was no one to assume their place. Fred punches out a big mouth at Midway Drugs and takes the fall for it, a complex exchange for us that maybe (or not) read simpler in 1946-47. Did then-viewers figure Mr. Mollett/Ray Teal for simply a bad guy who needed his block knocked off? Mollett says we were pushed into war “by a lot of Limeys and Reds,” a point Homer challenges by attacking the man with his hooks, a confrontation Fred breaks up when he slugs Mollett. But who’s really to blame for the melee?

Much of Best Years goes beyond black-and-white, though type casting of support players might suggest otherwise. Ray Teal was less established at this point for a louse, so did he really have severest reproof coming from Homer? Mollett/Teal is reading a front-page banner, “Senator Warns of New War.” How great a concern was this in 1946? We know new war didn’t come so soon as this, so are not concerned as surely some were in 1946. Mollett has a service pin, so why discount his opinion so readily? Maybe because he was Ray Teal, who like Charles Halton, Steve Cochran, and Howland Chamberlain, had faces we are predisposed to distrust, this the bane for actors whose presence implies ill conduct. Mollett does not strike back when Homer aggresses, shields himself rather than strikes. It is Homer who initiates the physical exchange by tearing Mollett’s pin from his lapel, sum of which incident loses Fred the Midway job for intervening. Does Homer have anger issues beyond physical disability we see? He broke a garage window earlier when children peeped in. Maybe Wilma is letting herself on for larger problems than she realizes. As with Al’s over-drinking, The Best Years of Our Lives hints happy endings we get may not stay altogether that way. The Mollett exchange is third-act crisis that will propel us toward surface resolution for all concerned, but to get there, each must surmount highest climbs, the stuff of best drama, if not of life itself.

Fred returns home jobless to find Marie entertaining “old friend” Cliff Scully (Steve Cochran), whom we glimpsed earlier during a club night out the Derrys do not enjoy with Peggy and her erstwhile escort. Cliff wears a service pin too, can’t understand Fred, “a guy like that with all this money lying around and he can’t get into it.” Cliff has been a star boarder with Marie, calls her “Sugar,” and figures to keep the lease on her bed. We concede at least one point to Cliff, who finds readjustment “easy, if you just take everything in your stride.” Cliff will thrive in postwar if he can stay out of trouble with police, him being Steve Cochran after all. Marie has developed a low opinion of Fred (“he’s not very bright”). A wall of mirrors she shares with Peggy during a powder room chat tips the resolution for both Fred and “Woody Merrill,” the boyfriend Peggy will soon discharge. Marie isn’t a bad consort for Cliff’s sort of guy. They are peas of a self-interested pod. Peggy is on the other hand ideal for Fred, but does she pamper him too much? We hope Fred will make a go of the junk business, for it does seem a last chance for him to “re-adjust.” His walk through a cemetery of bombers to swelling music is a last occasion for Fred living in troubled past, but will nightmares persist? Marie complained plenty about them, so yes, they wait upon Peggy to cope with, just as in offscreen movie life, Wanda Hendrix had finally to quit Audie Murphy, their marriage wrecked by his nocturnal torments. The Best Years of Our Lives even with a rapturous finish offers no pat answers, and that among many aspects is what makes and keeps it great.