The Popeye Specials

The Popeye Specials

There were 234 Popeye cartoons released to theatres between 1933 and 1957. Back then, you got them once a month, if that. Most of us that grew up with Popeye on television saw them in big dollops of an hour or more. That’s a minimum of six spinach helpings and goodness knows how many fistic exchanges between Popeye and Bluto. Some stations would play them on a kind of endless loop where it felt as though you were watching a single, never-ending cartoon. Even as a youngster, I would sometimes find myself yelling out to the hapless sailor, "Eat your damn spinach, and let’s get on with it!" Ship doors opening and closing in the credits meant a good one --- anything else, watch out. Those with King Features titles were to be avoided. Original Paramount logos were unheard of. For all we knew, these were made by "AAP", just like pre-48 Warner cartoons (or at the very least, they participated). The idea of a two-reel "Popeye Special" was quite unheard of when our stations played the package. Being 16-17 minutes in length, these three odd specimens were sometimes shelved altogether by stations disinclined to amend schedules accustomed to the conventional running time of six to seven minutes for cartoons. I once knew a UHF program director who purchased the complete Popeye group, only to extract Sindbad, Ali Baba, and Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp --- consigning them to a remote shelf where viewers would never see them. Indifference toward these remarkable subjects extended even to the owner’s failure to renew copyrights, and all three wound up in the public domain. Who at Paramount during the 1930’s would have dreamed these prestigious, and immensely popular, cartoon specials would come to such an ignominious finish?

There were 234 Popeye cartoons released to theatres between 1933 and 1957. Back then, you got them once a month, if that. Most of us that grew up with Popeye on television saw them in big dollops of an hour or more. That’s a minimum of six spinach helpings and goodness knows how many fistic exchanges between Popeye and Bluto. Some stations would play them on a kind of endless loop where it felt as though you were watching a single, never-ending cartoon. Even as a youngster, I would sometimes find myself yelling out to the hapless sailor, "Eat your damn spinach, and let’s get on with it!" Ship doors opening and closing in the credits meant a good one --- anything else, watch out. Those with King Features titles were to be avoided. Original Paramount logos were unheard of. For all we knew, these were made by "AAP", just like pre-48 Warner cartoons (or at the very least, they participated). The idea of a two-reel "Popeye Special" was quite unheard of when our stations played the package. Being 16-17 minutes in length, these three odd specimens were sometimes shelved altogether by stations disinclined to amend schedules accustomed to the conventional running time of six to seven minutes for cartoons. I once knew a UHF program director who purchased the complete Popeye group, only to extract Sindbad, Ali Baba, and Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp --- consigning them to a remote shelf where viewers would never see them. Indifference toward these remarkable subjects extended even to the owner’s failure to renew copyrights, and all three wound up in the public domain. Who at Paramount during the 1930’s would have dreamed these prestigious, and immensely popular, cartoon specials would come to such an ignominious finish?

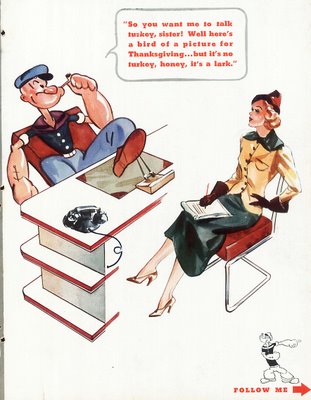

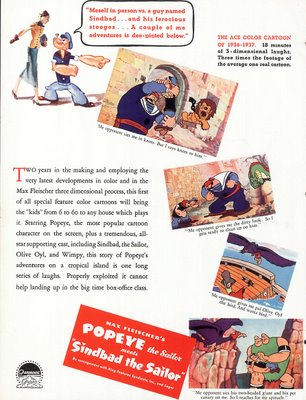

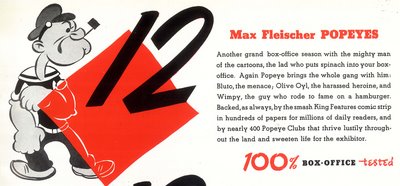

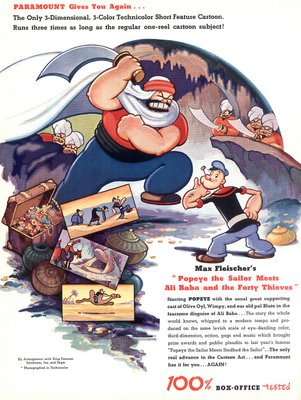

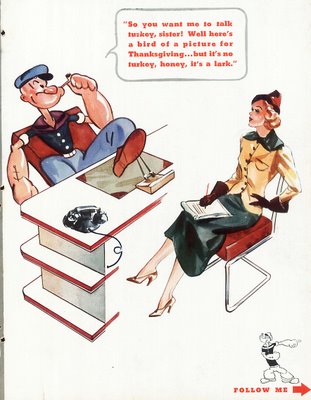

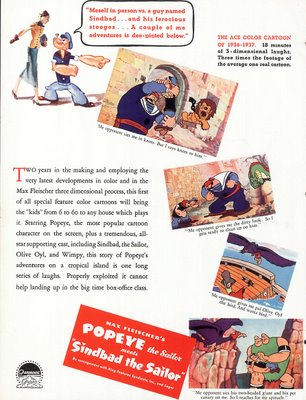

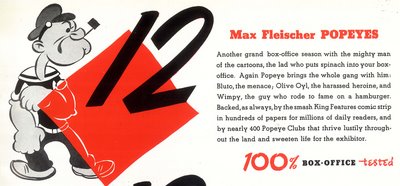

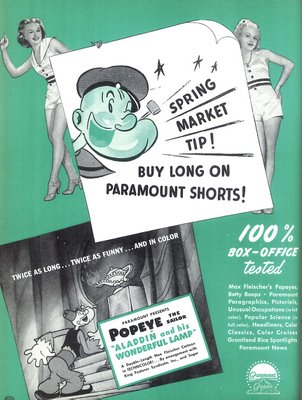

This theatre marquee will give you an idea of Popeye’s considerable following during that first decade after his introduction in 1933. He was a pure sensation from the moment of entering the scene with that soon-to-be-heard-in-every-schoolyard theme song, and the proliferation of Saturday morning "Popeye Clubs" in movie houses across the nation would confirm his almost deified status. Not since Mickey Mouse had a cartoon character done this. Exhibitors were beginning to express a preference for the Paramount series over Disney's beloved mouse as Popeye-crazed kids stormed the boxoffice for each new subject. This was beyond a mere fad, as adults loved him too. Even Disney had never attempted an extended length cartoon, but in 1936, Max Fleischer would. The creator of Popeye had invented a three-dimensional platform with a patented turntable process that would allow you to shoot cartoons in ways suggesting depth and detail unheard of in animation (the device shown here). While foreground characters moved, objects behind them occupied multiple levels of placement that made you feel as though the cartoon itself were being projected in 3-D. Fleischer used his process with black-and-white shorts for a couple of years, but it was the 1936 special, Popeye Meets Sindbad The Sailor, that really blew audiences away. Clocking in at sixteen plus minutes, Sindbad also featured a peppy score, more than lavish Technicolor animation (Popeye’s first in color), and customary wit that made these subjects a crowd favorite. Paramount expressed its confidence with elaborate trade ads seldom bestowed upon short subjects, and Sindbad was to be regarded in every way as something very special.

This theatre marquee will give you an idea of Popeye’s considerable following during that first decade after his introduction in 1933. He was a pure sensation from the moment of entering the scene with that soon-to-be-heard-in-every-schoolyard theme song, and the proliferation of Saturday morning "Popeye Clubs" in movie houses across the nation would confirm his almost deified status. Not since Mickey Mouse had a cartoon character done this. Exhibitors were beginning to express a preference for the Paramount series over Disney's beloved mouse as Popeye-crazed kids stormed the boxoffice for each new subject. This was beyond a mere fad, as adults loved him too. Even Disney had never attempted an extended length cartoon, but in 1936, Max Fleischer would. The creator of Popeye had invented a three-dimensional platform with a patented turntable process that would allow you to shoot cartoons in ways suggesting depth and detail unheard of in animation (the device shown here). While foreground characters moved, objects behind them occupied multiple levels of placement that made you feel as though the cartoon itself were being projected in 3-D. Fleischer used his process with black-and-white shorts for a couple of years, but it was the 1936 special, Popeye Meets Sindbad The Sailor, that really blew audiences away. Clocking in at sixteen plus minutes, Sindbad also featured a peppy score, more than lavish Technicolor animation (Popeye’s first in color), and customary wit that made these subjects a crowd favorite. Paramount expressed its confidence with elaborate trade ads seldom bestowed upon short subjects, and Sindbad was to be regarded in every way as something very special.

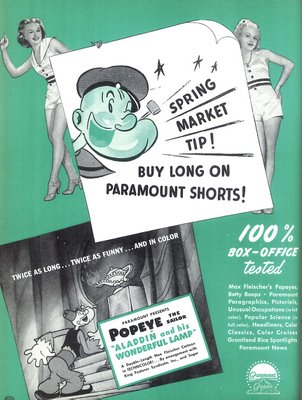

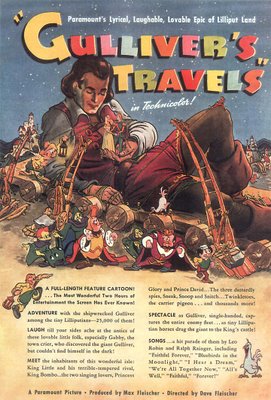

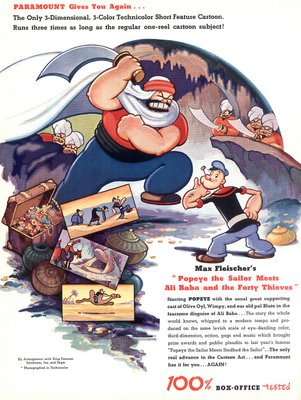

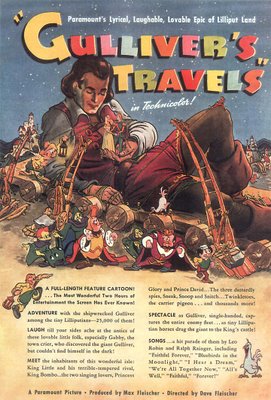

Max Fleischer was producing the Popeyes at a studio facility in New York. A lot of animation historians credit that setting with the gritty "street" feel these rough-and-tumble cartoons share. There's a nice grungy flavor about NY Popeyes you can’t help but notice when you watch a string of them. Anyway, the rough-and-tumble intruded upon Max by way of serious union trouble that threatened to shut down the whole operation, so Fleischer decamped to sunny Florida where unions were discouraged and slave wages were the order of the day. Much of the quality now suffered by a combination of Disney’s continued pillaging of Max’s best animators, and an overall dearth of talented artists. The relocated studio (its comfortable digs shown here) was forced to hire local art students, who got a crash course in cartooning when years of careful training was ongoing order of the day at rival Disney’s. Was it any wonder Max’s stuff suffered so in comparison to Walt’s? The second two-reel special, Popeye Meets Ali Baba, was another bell-ringer with the public (check out these exhibitor announcements), but the third and last of them, Aladdin’s Wonderful Lamp, was a step down, having been done on Floridian premises. The amazing success of Disney’s Snow White and The Seven Dwarfs inspired a flurry of Paramount memos directing Max Fleischer to quick- manufacture a facsimile of same, and Gulliver’s Travels was the unhappy result. Even if Fleischer hadn’t set out so brazenly to copy the Disney model, he’d still have run them a hopeless second in terms of technical proficiency, thanks to that largely amateur staff he’d been forced to utilize. A Gulliver’s Travels at 65 or so minutes with Popeye in the lead might have been fun, if the two-reelers were any indication, but Paramount wanted prestige first-run bookings, and their directives to Fleischer were non-negotiable. Sad to say, there would be no more Popeye specials. Indeed, Paramount would take over the animation unit altogether within a couple more years, and the Fleischers would be out. They’d never see a dime of residuals from all the cartoons they’d sweated to make.

Max Fleischer was producing the Popeyes at a studio facility in New York. A lot of animation historians credit that setting with the gritty "street" feel these rough-and-tumble cartoons share. There's a nice grungy flavor about NY Popeyes you can’t help but notice when you watch a string of them. Anyway, the rough-and-tumble intruded upon Max by way of serious union trouble that threatened to shut down the whole operation, so Fleischer decamped to sunny Florida where unions were discouraged and slave wages were the order of the day. Much of the quality now suffered by a combination of Disney’s continued pillaging of Max’s best animators, and an overall dearth of talented artists. The relocated studio (its comfortable digs shown here) was forced to hire local art students, who got a crash course in cartooning when years of careful training was ongoing order of the day at rival Disney’s. Was it any wonder Max’s stuff suffered so in comparison to Walt’s? The second two-reel special, Popeye Meets Ali Baba, was another bell-ringer with the public (check out these exhibitor announcements), but the third and last of them, Aladdin’s Wonderful Lamp, was a step down, having been done on Floridian premises. The amazing success of Disney’s Snow White and The Seven Dwarfs inspired a flurry of Paramount memos directing Max Fleischer to quick- manufacture a facsimile of same, and Gulliver’s Travels was the unhappy result. Even if Fleischer hadn’t set out so brazenly to copy the Disney model, he’d still have run them a hopeless second in terms of technical proficiency, thanks to that largely amateur staff he’d been forced to utilize. A Gulliver’s Travels at 65 or so minutes with Popeye in the lead might have been fun, if the two-reelers were any indication, but Paramount wanted prestige first-run bookings, and their directives to Fleischer were non-negotiable. Sad to say, there would be no more Popeye specials. Indeed, Paramount would take over the animation unit altogether within a couple more years, and the Fleischers would be out. They’d never see a dime of residuals from all the cartoons they’d sweated to make.

You can’t really see those three Popeye specials in anything like their original beauty nowadays. The usual ownership turf wars have put them all neatly on ice --- something about a squawk between Warners and King Features. If you just want to look at and hear these subjects, it’s easy enough to do that, and at no charge, on any one of a dozen free internet downloads where dreadful P.D. prints have been stored for an uncertain posterity. VCI has a nice DVD double-disc of public domain Popeye cartoons, including the three specials. They look as good there as I’ve ever seen them. Jerry Beck reported on Cartoon Brew the other day that MOMA was running Aladdin’s Lamp in a brand-new Warners restoration that promised to be wonderful. Too bad WB can’t get all of the Popeyes out in their own box set. As good as these things are, it’s a shame that the business of restoring and presenting them has to fall to private collectors and enthusiasts when all those original elements (or what’s left of them) are just evaporating on studio shelves. Bravo to VCI and others who have made the effort of preserving and sharing those Popeyes that have fallen into the public domain (and a surprising number of them have).

Update: Well, here's an old posting now happily obsolete as to unavailability of quality Popeye on DVD. Since May 18, 2006 when I wrote this, we've seen all the early Popeye shorts, including the color specials, released by Warners, with the promise of more to come.

You can’t really see those three Popeye specials in anything like their original beauty nowadays. The usual ownership turf wars have put them all neatly on ice --- something about a squawk between Warners and King Features. If you just want to look at and hear these subjects, it’s easy enough to do that, and at no charge, on any one of a dozen free internet downloads where dreadful P.D. prints have been stored for an uncertain posterity. VCI has a nice DVD double-disc of public domain Popeye cartoons, including the three specials. They look as good there as I’ve ever seen them. Jerry Beck reported on Cartoon Brew the other day that MOMA was running Aladdin’s Lamp in a brand-new Warners restoration that promised to be wonderful. Too bad WB can’t get all of the Popeyes out in their own box set. As good as these things are, it’s a shame that the business of restoring and presenting them has to fall to private collectors and enthusiasts when all those original elements (or what’s left of them) are just evaporating on studio shelves. Bravo to VCI and others who have made the effort of preserving and sharing those Popeyes that have fallen into the public domain (and a surprising number of them have).

Update: Well, here's an old posting now happily obsolete as to unavailability of quality Popeye on DVD. Since May 18, 2006 when I wrote this, we've seen all the early Popeye shorts, including the color specials, released by Warners, with the promise of more to come.

The Popeye Specials

The Popeye Specials There were 234 Popeye cartoons released to theatres between 1933 and 1957. Back then, you got them once a month, if that. Most of us that grew up with Popeye on television saw them in big dollops of an hour or more. That’s a minimum of six spinach helpings and goodness knows how many fistic exchanges between Popeye and Bluto. Some stations would play them on a kind of endless loop where it felt as though you were watching a single, never-ending cartoon. Even as a youngster, I would sometimes find myself yelling out to the hapless sailor, "Eat your damn spinach, and let’s get on with it!" Ship doors opening and closing in the credits meant a good one --- anything else, watch out. Those with King Features titles were to be avoided. Original Paramount logos were unheard of. For all we knew, these were made by "AAP", just like pre-48 Warner cartoons (or at the very least, they participated). The idea of a two-reel "Popeye Special" was quite unheard of when our stations played the package. Being 16-17 minutes in length, these three odd specimens were sometimes shelved altogether by stations disinclined to amend schedules accustomed to the conventional running time of six to seven minutes for cartoons. I once knew a UHF program director who purchased the complete Popeye group, only to extract Sindbad, Ali Baba, and Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp --- consigning them to a remote shelf where viewers would never see them. Indifference toward these remarkable subjects extended even to the owner’s failure to renew copyrights, and all three wound up in the public domain. Who at Paramount during the 1930’s would have dreamed these prestigious, and immensely popular, cartoon specials would come to such an ignominious finish?

There were 234 Popeye cartoons released to theatres between 1933 and 1957. Back then, you got them once a month, if that. Most of us that grew up with Popeye on television saw them in big dollops of an hour or more. That’s a minimum of six spinach helpings and goodness knows how many fistic exchanges between Popeye and Bluto. Some stations would play them on a kind of endless loop where it felt as though you were watching a single, never-ending cartoon. Even as a youngster, I would sometimes find myself yelling out to the hapless sailor, "Eat your damn spinach, and let’s get on with it!" Ship doors opening and closing in the credits meant a good one --- anything else, watch out. Those with King Features titles were to be avoided. Original Paramount logos were unheard of. For all we knew, these were made by "AAP", just like pre-48 Warner cartoons (or at the very least, they participated). The idea of a two-reel "Popeye Special" was quite unheard of when our stations played the package. Being 16-17 minutes in length, these three odd specimens were sometimes shelved altogether by stations disinclined to amend schedules accustomed to the conventional running time of six to seven minutes for cartoons. I once knew a UHF program director who purchased the complete Popeye group, only to extract Sindbad, Ali Baba, and Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp --- consigning them to a remote shelf where viewers would never see them. Indifference toward these remarkable subjects extended even to the owner’s failure to renew copyrights, and all three wound up in the public domain. Who at Paramount during the 1930’s would have dreamed these prestigious, and immensely popular, cartoon specials would come to such an ignominious finish?

This theatre marquee will give you an idea of Popeye’s considerable following during that first decade after his introduction in 1933. He was a pure sensation from the moment of entering the scene with that soon-to-be-heard-in-every-schoolyard theme song, and the proliferation of Saturday morning "Popeye Clubs" in movie houses across the nation would confirm his almost deified status. Not since Mickey Mouse had a cartoon character done this. Exhibitors were beginning to express a preference for the Paramount series over Disney's beloved mouse as Popeye-crazed kids stormed the boxoffice for each new subject. This was beyond a mere fad, as adults loved him too. Even Disney had never attempted an extended length cartoon, but in 1936, Max Fleischer would. The creator of Popeye had invented a three-dimensional platform with a patented turntable process that would allow you to shoot cartoons in ways suggesting depth and detail unheard of in animation (the device shown here). While foreground characters moved, objects behind them occupied multiple levels of placement that made you feel as though the cartoon itself were being projected in 3-D. Fleischer used his process with black-and-white shorts for a couple of years, but it was the 1936 special, Popeye Meets Sindbad The Sailor, that really blew audiences away. Clocking in at sixteen plus minutes, Sindbad also featured a peppy score, more than lavish Technicolor animation (Popeye’s first in color), and customary wit that made these subjects a crowd favorite. Paramount expressed its confidence with elaborate trade ads seldom bestowed upon short subjects, and Sindbad was to be regarded in every way as something very special.

This theatre marquee will give you an idea of Popeye’s considerable following during that first decade after his introduction in 1933. He was a pure sensation from the moment of entering the scene with that soon-to-be-heard-in-every-schoolyard theme song, and the proliferation of Saturday morning "Popeye Clubs" in movie houses across the nation would confirm his almost deified status. Not since Mickey Mouse had a cartoon character done this. Exhibitors were beginning to express a preference for the Paramount series over Disney's beloved mouse as Popeye-crazed kids stormed the boxoffice for each new subject. This was beyond a mere fad, as adults loved him too. Even Disney had never attempted an extended length cartoon, but in 1936, Max Fleischer would. The creator of Popeye had invented a three-dimensional platform with a patented turntable process that would allow you to shoot cartoons in ways suggesting depth and detail unheard of in animation (the device shown here). While foreground characters moved, objects behind them occupied multiple levels of placement that made you feel as though the cartoon itself were being projected in 3-D. Fleischer used his process with black-and-white shorts for a couple of years, but it was the 1936 special, Popeye Meets Sindbad The Sailor, that really blew audiences away. Clocking in at sixteen plus minutes, Sindbad also featured a peppy score, more than lavish Technicolor animation (Popeye’s first in color), and customary wit that made these subjects a crowd favorite. Paramount expressed its confidence with elaborate trade ads seldom bestowed upon short subjects, and Sindbad was to be regarded in every way as something very special.

Max Fleischer was producing the Popeyes at a studio facility in New York. A lot of animation historians credit that setting with the gritty "street" feel these rough-and-tumble cartoons share. There's a nice grungy flavor about NY Popeyes you can’t help but notice when you watch a string of them. Anyway, the rough-and-tumble intruded upon Max by way of serious union trouble that threatened to shut down the whole operation, so Fleischer decamped to sunny Florida where unions were discouraged and slave wages were the order of the day. Much of the quality now suffered by a combination of Disney’s continued pillaging of Max’s best animators, and an overall dearth of talented artists. The relocated studio (its comfortable digs shown here) was forced to hire local art students, who got a crash course in cartooning when years of careful training was ongoing order of the day at rival Disney’s. Was it any wonder Max’s stuff suffered so in comparison to Walt’s? The second two-reel special, Popeye Meets Ali Baba, was another bell-ringer with the public (check out these exhibitor announcements), but the third and last of them, Aladdin’s Wonderful Lamp, was a step down, having been done on Floridian premises. The amazing success of Disney’s Snow White and The Seven Dwarfs inspired a flurry of Paramount memos directing Max Fleischer to quick- manufacture a facsimile of same, and Gulliver’s Travels was the unhappy result. Even if Fleischer hadn’t set out so brazenly to copy the Disney model, he’d still have run them a hopeless second in terms of technical proficiency, thanks to that largely amateur staff he’d been forced to utilize. A Gulliver’s Travels at 65 or so minutes with Popeye in the lead might have been fun, if the two-reelers were any indication, but Paramount wanted prestige first-run bookings, and their directives to Fleischer were non-negotiable. Sad to say, there would be no more Popeye specials. Indeed, Paramount would take over the animation unit altogether within a couple more years, and the Fleischers would be out. They’d never see a dime of residuals from all the cartoons they’d sweated to make.

Max Fleischer was producing the Popeyes at a studio facility in New York. A lot of animation historians credit that setting with the gritty "street" feel these rough-and-tumble cartoons share. There's a nice grungy flavor about NY Popeyes you can’t help but notice when you watch a string of them. Anyway, the rough-and-tumble intruded upon Max by way of serious union trouble that threatened to shut down the whole operation, so Fleischer decamped to sunny Florida where unions were discouraged and slave wages were the order of the day. Much of the quality now suffered by a combination of Disney’s continued pillaging of Max’s best animators, and an overall dearth of talented artists. The relocated studio (its comfortable digs shown here) was forced to hire local art students, who got a crash course in cartooning when years of careful training was ongoing order of the day at rival Disney’s. Was it any wonder Max’s stuff suffered so in comparison to Walt’s? The second two-reel special, Popeye Meets Ali Baba, was another bell-ringer with the public (check out these exhibitor announcements), but the third and last of them, Aladdin’s Wonderful Lamp, was a step down, having been done on Floridian premises. The amazing success of Disney’s Snow White and The Seven Dwarfs inspired a flurry of Paramount memos directing Max Fleischer to quick- manufacture a facsimile of same, and Gulliver’s Travels was the unhappy result. Even if Fleischer hadn’t set out so brazenly to copy the Disney model, he’d still have run them a hopeless second in terms of technical proficiency, thanks to that largely amateur staff he’d been forced to utilize. A Gulliver’s Travels at 65 or so minutes with Popeye in the lead might have been fun, if the two-reelers were any indication, but Paramount wanted prestige first-run bookings, and their directives to Fleischer were non-negotiable. Sad to say, there would be no more Popeye specials. Indeed, Paramount would take over the animation unit altogether within a couple more years, and the Fleischers would be out. They’d never see a dime of residuals from all the cartoons they’d sweated to make.

You can’t really see those three Popeye specials in anything like their original beauty nowadays. The usual ownership turf wars have put them all neatly on ice --- something about a squawk between Warners and King Features. If you just want to look at and hear these subjects, it’s easy enough to do that, and at no charge, on any one of a dozen free internet downloads where dreadful P.D. prints have been stored for an uncertain posterity. VCI has a nice DVD double-disc of public domain Popeye cartoons, including the three specials. They look as good there as I’ve ever seen them. Jerry Beck reported on Cartoon Brew the other day that MOMA was running Aladdin’s Lamp in a brand-new Warners restoration that promised to be wonderful. Too bad WB can’t get all of the Popeyes out in their own box set. As good as these things are, it’s a shame that the business of restoring and presenting them has to fall to private collectors and enthusiasts when all those original elements (or what’s left of them) are just evaporating on studio shelves. Bravo to VCI and others who have made the effort of preserving and sharing those Popeyes that have fallen into the public domain (and a surprising number of them have).

Update: Well, here's an old posting now happily obsolete as to unavailability of quality Popeye on DVD. Since May 18, 2006 when I wrote this, we've seen all the early Popeye shorts, including the color specials, released by Warners, with the promise of more to come.

You can’t really see those three Popeye specials in anything like their original beauty nowadays. The usual ownership turf wars have put them all neatly on ice --- something about a squawk between Warners and King Features. If you just want to look at and hear these subjects, it’s easy enough to do that, and at no charge, on any one of a dozen free internet downloads where dreadful P.D. prints have been stored for an uncertain posterity. VCI has a nice DVD double-disc of public domain Popeye cartoons, including the three specials. They look as good there as I’ve ever seen them. Jerry Beck reported on Cartoon Brew the other day that MOMA was running Aladdin’s Lamp in a brand-new Warners restoration that promised to be wonderful. Too bad WB can’t get all of the Popeyes out in their own box set. As good as these things are, it’s a shame that the business of restoring and presenting them has to fall to private collectors and enthusiasts when all those original elements (or what’s left of them) are just evaporating on studio shelves. Bravo to VCI and others who have made the effort of preserving and sharing those Popeyes that have fallen into the public domain (and a surprising number of them have).

Update: Well, here's an old posting now happily obsolete as to unavailability of quality Popeye on DVD. Since May 18, 2006 when I wrote this, we've seen all the early Popeye shorts, including the color specials, released by Warners, with the promise of more to come.

I learn so much reading your articles!

ReplyDeleteI laughed when I read, "For all we knew, these were made by 'AAP', just like the Warner cartoons (or at the very least, they participated)."

For the longest time I thought all the RKO films were made by MCA (which I must admit, had an impressive animated logo, with its slowly turning panels and stentorian Warner's-like music). Them or C & C Soda.

Thanks for yet another informative post! You always seem to manage to put together a quality combination of words and pictures.

ReplyDeleteRegarding the two-reel special Popeye shorts, there is at least one DVD that features good-quality transfers including real Paramount logos:

Popeye: Original Classics from the Fleischer Studio

I own this DVD and can report that the transfers of the color shorts are very good indeed.

Dave

Thank you for another great cartoon post!

ReplyDeleteWPIX-11 used to air the Popeye cartoons in NYC. You'd never see the "specials" during the Monday-Friday show, but they'd turn up now and then on Sunday mornings - counterprogramming to WNEW's Wonderama. Apart from the lousy a.a.p. opening and closing (with music that never matched), the "specials" were always a joy. I even liked Aladdin better than Ali Baba, but that may have been due to a poor soundtrack on the latter film. (It seemed to me that most of Popeye's mumbling got drowned out by the orchestra score.)

I, too, own the DVD mentioned by theinscrutableone; it was produced by Thunderbean and it's HIGHLY recommended, even more than the VCI package (Jerry Beck might agree). The restorations are gorgeous considering they were done from prints (albeit good ones), the Paramount logos are a real treat, and as for the extras... "well, blow me down!"