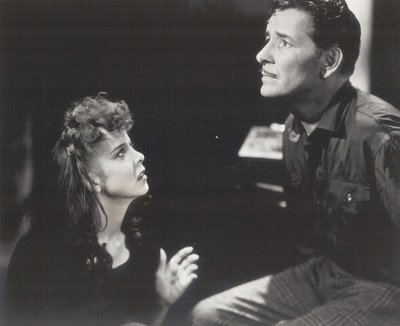

Monday Glamour Starter --- Ida Lupino

Ida Lupino might have enjoyed a glorious old age had luck held out a little longer, her mantle buckling beneath the weight of awards she would have collected for pioneering efforts as a director in a notoriously male dominated industry. The women’s studies industry was also too late to Ida’s door for interviews and inspiration. It’s not that she died too soon. That didn’t happen until 1995, but for at least ten years previous, she kept silence behind closed gates and allowed few to enter. The little red devils she had alluded to often were back in to stay, a personality tormented by dark moods and melancholy living in anything but splendid isolation. Artistic personalities are often troubled, serenity not among gifts they are born to. Ida Lupino was high-strung to a point of caricature. Servicemen encountering her at the Hollywood Canteen would request that she scream. Guests at parties would come up and say, Ida, go crazy, as if this were some parlor trick she could switch on and off like Jimmy Durante doing Umbriago. She had a way of exploding on camera, and off as well. A breakdown she staged in They Drive By Night convinced the town she was as cracked in private life. Like Bette Davis, Ida's was a line in high-octane melodrama, public taste for that diminishing after the war. Like other actresses who during conflict had the field largely to themselves, Lupino would have to retrench in order to survive. Directing was borne as much of necessity as inclination, and though she would continue to act into the 70's, it was really behind the camera that Ida Lupino found a greater satisfaction.

There were seven generations of Lupinos in show business. Ida said late in life that she only got into it to please her father and uphold tradition, but judging by her temperament and appetite for flamboyance, I’d say the fruit fell pretty near the tree. Histrionics were part of her daily routine. As a child in England, she went door to door telling the neighbors of beatings and starvation at home, just to see how they’d react. No truth in that at all, but it did initiate a lifelong habit of embroidering the truth for the sake of impact and showmanship, things she knew all about. There were psychic powers she inherited, and hanged if there might have been something to that, for she managed to anticipate a number of deaths and disasters among friends and family in years to come. Stage and (limited) film work in the UK got her noticed at Paramount, and they brought her over ostensibly to test for 1933’s Alice In Wonderland, but she didn’t want the lead (!), and loudly voiced a desire to play mature parts instead. Being yet a teenager, she did manage to get into adult fare without the encumbrance of ingenue work, but a bout with polio nearly put the whole career aground within months of her US arrival. Interviewers found Lupino charmingly arrogant --- I cannot tolerate fools! --- but much of this was immaturity blossoming in the face of newfound celebrity. The Light That Failed was a 1939 hit with Ronald Colman that really put her over. Edgy, dangerous types became her stock in trade. Warners came calling at $2000 a week, though she reserved the right to do outside pictures at Fox. Rebellion and suspensions at WB were inevitable. She turned down Juke Girl, King’s Row, and Captains of the Clouds . Among ones she did were High Sierra (excellent), The Hard Way (also good), and The Man I Love (which had, has, a following). Ida Lupino was arresting in the right kind of picture, but luckless in other ways, being accident-prone and out sick a lot. Having Bette Davis around the place didn’t help either, since best parts at Warners always went by we-know-who first.

Her WB pact ended on a sour note in 1947, Ida Lupino forced now to gamble. Second husband Collier Young teamed with her in setting up an independent unit called The Filmmakers --- not an unsound venture to go it alone outside collapsing studio walls, and Lupino had name enough to find backing for innovative subject matter she wanted to film. Not Wanted was a profitable beginning --- a story of unwed motherhood with Ida often filling in for credited director Elmer Clifton --- followed by Outrage, the title of which refers to a rape, and Never Fear, which dealt with polio. In wake of these, Lupino was a talk of the town, Filmmakers setting up shop at RKO. That boded well but for wily Howard Hughes taking advantage of Collier Young’s negotiating weakness, locking the pair into a no-win contract, for which Lupino never forgave her husband. Now even money pictures brought nothing back to Filmmakers, Hughes skimming gravy before the Youngs could dip their bread. Greater revenue for Ida came not from features she directed, but melodramas in which she performed, such as Beware, My Lovely and On Dangerous Ground. Young got the idea Filmmakers should distribute as well as produce. Ida knew that would come a cropper. They tried to recoup by accepting product placement in their movies. Coca-Cola, United Airlines, and Cadillac kicked in for The Bigamist, and Ida had to emote in parts of Private Hell 36 with an enormous Pabst Blue Ribbon beer bottle display looming over her shoulder. Independent production was a real salvage operation in those days, like prying a quarter off wet cement after the truck’s run over it. Crews opted for location whenever they could. Stage rentals were an unnecessary expense. A noir like Private Hell 36 really benefited from streets, bars, and trailer parks where it was shot. Those who could survive a 50’s indie race were well equipped to conquer early television as well. At a time when feature prospects were fast rotting on the vine, Ida Lupino made her smart move in that direction.

It was Dick Powell who paved the way of transition for the actress and director, luring her to his Four Star umbrella and valuable experience in rough-and-tumble ways of video production. By now, she had divorced Collier Young and married actor Howard Duff. Together they had a hit series called Mr. Adams and Eve, which got back some measure of on-screen fame Lupino lost during the interim. Series directing became steady work. Richard Boone used her in a group of Have Gun – Will Travels, and an aptitude for suspense programs got her work on Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Thriller, and The Twilight Zone. She was known as the most tactful of directors --- her chair canvas read Mother. All of this carried her through the 60's. She even called Action for some Gilligan’s Island episodes. On the personal front, Dick Powell called when he found out he had cancer and requested she spend the final months with him (June Allyson was seeking a divorce at the time). They got together until the last few weeks when June came back. This was something I did not know until reading a splendid Ida Lupino biography by William Donati. According to Donati, who spent lots of time with Lupino during her sad final years, the actress/director pretty much withdrew after memory lapses made it difficult to retain dialogue. There was a Charlie’s Angels appearance she barely got through, then retreat to the quiet of home. She should have received a special Academy Award for all she accomplished. Filmmakers output she directed has been combined for Blu-Ray release, these doing much to establish Lupino as a pioneer both behind, and in front of, cameras.

1 Comments:

'...as if this were some parlor trick she could switch on and off like Jimmy Durante doing Umbriago."

Few others on the blogosphere can write so well, or make a reference both arcane and laugh-out loud funny. Where were you when I needed a comrade in high school?

Post a Comment

<< Home