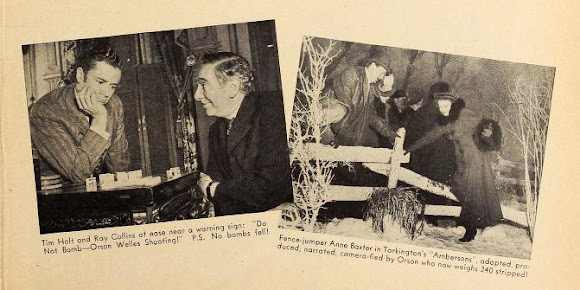

Happy Ambersons Thanksgiving

The Spell Welles Still Casts

Watching The Magnificent Ambersons led me again to ponder what-ifs as to fate of Orson Welles' second feature for RKO, and how fate dealt us, and him, something very different from what was intended. I looked back to see when The Magnificent Ambersons came first into collecting life. Record shows it was June 1978, an “original” 16mm print gotten from Canada for $200. Such a thing was rare as a hen’s tooth in those days. I “taught” the Ambersons for a Community College course a few years later, ran the print on their old “Jan” military surplus projector, then described for the class all of lost scenes as enumerated in Charles Higham’s book, The Films of Orson Welles. My course was called “The Great Romantic Films,” into which I shoehorned the Ambersons, for even then, I was hung up on what was had, then lost, from Welles’ work, upshot being I can never come to this film without getting all misty over what happened to it, a situation persistent since that Canadian print limped through the door in 1978.

Among questions that arise during an umpteenth view of The Magnificent Ambersons: Why didn’t Aunt Fanny invest her inheritance with Eugene Morgan instead of the headlight company? Eugene’s had to have been a safer bet, based on the factory visit he hosted where Fanny was present. He also would move heaven and earth to protect her investment, out of affection for the family if nothing else. He might even have married Fanny someday, once the estate and George’s future was sorted out. The film’s ending, what I refer to as Freddie Fleck’s The Magnificent Ambersons, suggests that Eugene will take charge of the family’s welfare, what is left of it.

Toward scratch of itch that is the Ambersons came 2/2018 dredge of '42 ads where I could find them, wanting to know who/when played it … search continuing for mythical occasion where Welles ran as a second feature to Mexican Spitfire Sees a Ghost. Historians assure us it did --- but I say, show me. Also there was Pomona dive to better comprehend The Fleet’s In that pleased more those wretched gum-poppers who would not embrace the Ambersons as we so wisely do.

Every existing foot of Ambersons rouses a same question, might the whole thing still exist?, a topic well-flogged at Greenbriar and elsewhere (see reader comments from a 2010 post). Assuming Ambersons was not shipped back to RKO along with elements for It’s All True (and destroyed upon receipt in California), might it have been rescued by a South American collector, or archive? There was testimony from those who claimed to have seen Ambersons during the 50’s or 60’s, in stored cans if not on Brazilian screens. As to evidence that RKO sent instruction for the film to be disposed of on site, that order carried out … or not, I would cite TV stations duly signing a “Certificate of Destruction” for 16mm feature packages, at times containing hundreds of titles, then back-dooring the lot to collectors. Believe me, this happened plenty. To have burned all that asset would be a same as century notes put to a dried leaf bonfire. How many low paid station employees turned down cash (always cash) for stuff nobody cared about? 16mm was all a more useless once video transmission got hold, stations the happier to free up shelf space, so no questions asked when pallets of film went missing (other than perhaps, where’s my rake-off?). Bet south-of-border RKO staffers in 1942 were as pliable. Here’s luck to the young man who plans yet to fly down and investigate possibilities, these to include interviewing families of one-time collectors (good idea). That Ambersons could still exist in this circumstance is no mere flight of fancy.

Favorites work all a better where seen through hopefully matured eyes. When it’s The Magnificent Ambersons, potential for fresh insight is immense. My sympathy was always with the family, even George, especially George. Seems to me Eugene made a wrong move from the moment he was introduced, Remember you very well indeed an admitted rote politeness from George, to which Eugene, putting on a little much to impress lost love Isabel, replies George, you never saw me before in your life, but from now on, you’re going to see a lot of me, George annoyed by a stranger behaving so familiar toward his mother, Joseph Cotten the more intimidating as he is taller than either. For Eugene to enter this house, after so many years, as though it were to an extent his because of a prior, and long past, relationship with the Ambersons … well, I don’t blame George for being immediately put off by him (George: He certainly seems to feel awfully at home here, the way he was dancing with Mother and Aunt Fanny). Worse is Eugene letting it be clear that Isobel would have been his wife but for a mishap with the viola for his botched serenade. Older Ambersons tease him over this, but realize that indeed, but for his trip-and-fall, Eugene might have become putative head of the family. And what would he have done given that license? I suspect the Ambersons would have held on to their fortune, built now upon automobiles rather than downtown properties, but would Eugene have replaced their lovely hardwood flooring with tile?

There is an amazing site dedicated to The Magnificent Ambersons, overseen by writer and historian Joseph Egan. Among other things, he has reconstructed the film as it would have played at 131 minutes, using a cutting continuity found in RKO archives, plus existing images from footage otherwise removed prior to Ambersons’ spring 1942 release at 88 minutes. I find myself almost pathetically eager to embrace The Magnificent Ambersons as it is presently constituted, a way to cope, I suppose, with sad fact we will not likely see the whole of it again. What invariably happens is, I watch the movie, then exhaust myself for two-three days reading yet again what became of it --- the Pomona preview, desperate communiques back-forth with Welles in Brazil, RKO staff trying to adjust Ambersons to conventional fit. Robert Wise, a more than capable editor, was obliged to speed the pace, “lighten” mood if possible (Ambersons having been declared a hopeless downer by panicked execs), to trim fat from bone that was narrative. This of course was not the movie Orson Welles set forth to make, but was Wise, and concerned others, altogether misguided? Those who subscribe to Welles Against The World say yes, but I’m not as sure.

Consider The Magnificent Ambersons running 131 minutes. That’s a mighty lot of aristocracy crumbling. There are some scenes editor Wise wisely took out. Welles from long distance agreed on a number of trims, and I don’t think that was altogether because he felt pressured to do so. He knew Ambersons needed tightening. Had Welles come home in time to save it, would he and Wise have left The Magnificent Ambersons at 131 minutes, Welles insisting it stay at that length? I think the only point he might have been intractable on was the ending at the boarding house, which to Welles was the entire point of Ambersons, or so he said over years to come. Everyone else seems to have viewed that finish as finish for the movie, poisonous to public acceptance. Were they right? It reads heavy at Joseph Egan’s site. He even found the old vaudeville song that backgrounds dialogue between Joseph Cotten and Agnes Moorehead, and gives us a recording to listen to as we peruse their dialogue. Welles was too far away to realize how serious his Ambersons problem was. Had he gotten back, I’d like to think The Magnificent Ambersons would have resolved at 105 or so minutes. Notwithstanding changes RKO made to the third act, I say Robert Wise did a fine job of editing given incredibly stressed circumstances (eighteen-hour days, every day, to meet scheduled release). Welles said later that Ambersons was “his” movie up to Major Amberson dying. There have been more hope-than-reality moments where I’ve thought Wise’s version was as good, maybe better, than a “complete” Ambersons would have been. Again, that’s avoidance of truth that even Wise acknowledged, in fact emphasized. He knew this was a great picture he was obliged, for the sake of his livelihood, to deface. Still, I believe there would be risk in finding The Magnificent Ambersons at 131 minutes. Would we like it more, even as much, as what we have now?

5 Comments:

Maybe I wouldn't like it more, but I'd want to see it.

Peter Bogdonavich tells a story about how he was flipping through the tv channels and came across "Ambersons". Welles, his houseguest, refused to watch. But, while standing in the doorway, simply cried at what could have been.

This and Erich Von Stroheim's GREED and perhaps FOOLISH WIVES.

I'd love to see a director's cut of Richard Williams's "Cobbler and the Thief", but even in the mutilated version it's clear Williams intended the two lead characters to be mute with long sequences free of dialogue -- maybe a hard sell for modern audiences. The released version has both characters providing relentless voiceovers, with the hero talking in new scenes by other hands.

In Billy Wilder's "Private Life of Sherlock Holmes", what we have is still a solid, superior movie. Only one missing sequence really makes a difference: the flashback to Holmes's college days, which adds resonance to the main plot (a few lines during a train ride offer an alternative narrative). Other scenes, reconstructed on the DVD, are entertaining but don't leave visible holes.

Coppola had a neat idea in rebuilding the first two Godfather films into a television serial. Surprised nobody has thought to do the same with the Harry Potter movies, which evidently made plentiful cuts purely for length. A public that has embraced binge watching would welcome a few extra hours.

Dan Mercer considers THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS:

“The Magnificent Ambersons” is such a superb film, even in its present “defaced” state, that it almost seems churlish to mourn it for what might have been. There are few other films that meld human character and ideas and social dynamics so seamlessly and so true to life. That it could have been even greater, and that this greatness was so close to being realized, is heartbreaking.

I do not know that Booth Tarkington was familiar with the thoughts of the economist Henry George, but I imagine that he was. Most intelligent Americans then were, even though George has become as obscure today as Tarkington is. His big idea was that land is the source of all wealth. Prosperity, then, is land plus ideas. The Ambersons had become rich as landlords, providing the means that other men would use in producing wealth. That model was becoming outmoded, especially as new ways of transportation took people away from the downtown where their property was concentrated. Eugene Morgan had a better idea, the automobile, and this not only made him wealthy, but accelerated the destruction of the Amberson’s wealth.

Aunt Fanny would have been wise to have placed her money with Eugene, for just the reasons you say. He would have safeguarded it and the success of his business would have become hers. I cannot help but believe, however, that he would have been the last person she would have turned to in that way. She was in love with him, and he loved someone else. As much as George, she did not want Eugene to enjoy happiness with Isobel, though her methods were less direct. Hers were little cuts, deftly made, though in the end, the wounds inflicted were upon herself.

George Minafer is the central character and the great weakness of the film as it was released. He is the grandson of Major Bennett, the most magnificent of the Ambersons, and a most unpleasant individual: selfish, overly indulged, and lacking in kindness. His willfulness is the axis around which the story turns, everyone either bending to it or going their own ways, apart from him and his family. Even as the family’s fortunes are eroding, he cruelly destroys his mother’s possible happiness with the unworthy Eugene Morgan, which happiness, incidentally, would have become the family’s as well. In the novel and, I believe, in the film as intended, he would find redemption in hard work and newly assumed responsibility. In a way, this does come to pass. The new ending of the film prepared in Welles’ absence, is still substantially the same. What has changed are the incidents leading up to it. All the subtlety and nuance that characterizes the first two thirds of the film are largely absent, so the possibility of redemption and transcendence is not fully realized. It is more like a coda to a piece that is largely at odds with what preceded it.

I understand that Tod Browning’s “The Unknown” was for a time considered a lost film, until a print was discovered in a French archive. Its title as translated, “L’Inconnu,” had caused it to be stored with cannisters in a section marked “Inconnu,” containing unidentified reels of film. Possibly somewhere, the portions of film Orson Welles had worked on are still in existence, misidentified, and waiting for the time in which someone will chance upon them. There have been too many discoveries to allow for any certainty that nitrate film invariably disintegrates, and I have lived long enough to know that nothing occurs entirely by chance. We can hope then that “The Magnificent Ambersons” will one day appear in the form that was intended. In the meantime, in its present form, it is indeed a superb film.

John, I note that you've been trying to find evidence that THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS played under MEXICAN SPITFIRE SEES A GHOST. All the ads I've seen have the Spitfire as the second feature, when they played together at all -- usually AMBERSONS played above something else, and not always an RKO picture.

Another possible Spitfire connection: I remember reading somewhere that a Welles soundstage was shut down by RKO because the Mexican Spitfire unit was scheduled to use it next. I bow to the Welles scholars to confirm or dismiss this one.

Post a Comment

<< Home