Do They Like You Best When You Play Yourself?

|

| That's Hal Wallis Hovering Over Eddie and Paul |

Personality The Cake, Versatility The Icing

Under head of disliking someone who has too much in common with you comes Edward G. Robinson and Paul Muni, two peas in a Warner pod who had strong personalities plus versatility, but could not abide one another, as stated flat in Robinson’s memoir, “I disliked Muni and Muni detested me.” Being “versatile” saw Robinson/Muni engage strikingly different parts, never so hemmed in as many of peers. Tough customers at a start, bound by that profile you’d think, but these two itched to go beyond brute man mode, Muni early declaring himself done with it, Robinson keeping avenue open should career flux oblige him to again snarl and wield a gat (it would, and often). Theirs in the day was adjudged to be “acting” in a sense of no role beyond either, exaggeration on its face that Robinson/Muni sensed better than critics draping them in laurel.

|

| Joseph Jefferson as Rip Van Winkle |

|

| Maude Adams ... Writers Claim She Was Not a Beauty ... Sez Them! |

Wrangle between performance bound by “personality,” as opposed to “can-do-anything,” (and should) fed debate and discussion among actors from a thesping start, consensus no nearer now than in the nineteenth century when braver voices (some prominent) lauded players who put aspects of themselves into whatever part they took, audiences not only appreciative, but insistent that they do so. A so-called “cult of personality” arrived with greater realism the stage would embrace, actors becoming more like us as individuals rather than representatives for the American spirit. Versatility could still be admired, but loyalty, in fact love, was a performer’s reward for choosing those parts that fit best. Joseph Jefferson could do, had done, a mosaic of roles over a long career, but it was as Rip Van Winkle that he would gain immortality. Maude Adams, basking in warmth her Peter Pan generated, knew too well, and from humbling experience, that Shakespeare was ice flow to be avoided, at least for her elfin type. The list went on: James O’Neill a nonpareil Count of Monte Carlo, even if trapped by the role, Edwin Booth a Hamlet or Richelieu for the ages (above right), but wise enough to duck Othello. People came less to see Hamlet than Booth as Hamlet, his singular impersonation their value for money. So never imagine the movies introduced a star system. It was well in place before first flickers lighted a screen.

|

| William Gillette Shows Off The Personal Railroad At His Connecticut Estate |

Most prosperous of artists knew their strength, and limits. Each acclaimed great, their public responded to favorites playing a character as much or more than the character being played, each role but variation on what the actor or actress had offered before. Critics said this was valuing outward appearance rather than proven acting skill. Aged in wood from birth in 1858, and a thousand parts played since, Otis Skinner spoke for an old guard raised on the road or in stock companies, “Acting has changed. Versatility, once the choicest possession of the player, is being bred out of the stock. Actors are no longer chosen for their ability to express every and any character, but for their physical and temperamental approximation to one particular character.” So how was this a bad thing, answered others, among them William Gillette, who wrote his own best vehicles, and was legendary as Sherlock Holmes. Gillette spoke to personality as any actor’s defining asset. Citing a “plain fact” to the New York Times, he claimed “personality as the most important thing in really great acting,” this a quote from 1914 as applied to stage artists, a star system in movies still emerging at the time. Gillette challenged a consensus. Stock companies throughout the country had after all prided themselves on membership that could do it all, and did. Veterans from “palmy days” longed for a lost era when to act was to act whatever needed acting. Was this not the truest measure of a professional’s skill? Gillette thought not, pointing out that times, and audience expectation, had changed. Realistic acting required a closer identity between part and player. “Personality is the most singularly important factor for infusing the Life-Illusion into modern stage creations that is known to man,” said Gillette. Actors “playing themselves” need not apologize for doing so.

Movies took this many steps further as stars created by screens made the audience-artist identification far more intense than anyone could have imagined. Old-timers saw this and were threatened by it. How could a comparative beginner who made a specialty for him/herself rise overnight to fame no stage artist dreamt of? Yet it happened, and repeatedly. Close-ups were a factor, in fact the determining one. Suddenly we were near enough to feel nuance and expression as our own, a level of intimacy not attainable no matter how close one sat to a stage. The meteoric rise of a Chaplin or Mary Pickford went beyond anyone’s experience, but if electric lights and motor cars were possible, then peace must be made with this, even as many a grey eminence resisted (see Tully Marshall kick traces in early 30’s interviewing). These of a passing generation kept faith that to act was to enact whatever was put before them. Maybe this would do for character and small parts, but stars weren’t born by such route, and most actors, after all, longed to be stars.

Edward G. Robinson and Paul Muni were character stars. Romantic leads sat uneasily with them, both the better for that, as options widened to include youth-to-elder sagas (Muni with The World Changes, Robinson and Silver Dollar), social-driven themes (much of Muni), and show-offness of dual roles to offer wide range for one ticket. Having shown capacity to startle, Robinson with Little Caesar, Muni with Scarface and Fugitive, both could show amplitude to a public safely aware of dynamism they had in reserve. Throughout years to follow, we sensed the killer instinct behind whiskers Robinson and Muni often wore. Our knowing they could return to basics made variances tolerable. Fun was when restraint was served in a same frame with hard cases we liked Robinson or Muni to play. Humble-in-extreme The Man With Two Faces (72 minutes) has Robinson being “himself” for a first half (an actor of forceful E.G. mien), then showing up bearded as a timid scholar (mere disguise… he’s committed murder and is hiding behind the muff). His next feature had Robinson, meek again as a bookkeeper and butt of office jokes, met by a snarling “Caesar” doppelganger (also Eddie) on the lam. This was The Whole Town’s Talking in 1935, which by then saw a whole town talking about Robinson as one who could do most, if not all, of what dramatists devised.

Paul Muni’s was a more distinct about-face, maybe too much considering legacy he left and how we remember him. No longer would Muni be an ordinary Joe at a reporter desk (Hi, Nellie!), a sort of part to invite comparison with livelier wires Cagney, Lee Tracy, others more at home in city rooms. The Story of Louis Pasteur was his own radical idea, at least going forward with it, a departure from what Muni played to then. Warners resisted, so far as the star flattered himself in recalling (practically “snuck” it past them, he said). Pasteur then was the plunge, his Academy statue the reward, “Mr. Muni” addressee for Warner memos composed from kneed position in deference to status now his. Rugged up to then in Bordertown and Black Fury, mitigated only to extent of ethnic tilt laced with accent, Muni’s unadorned face was still there to look at, till Pasteur and Zola belled the cat, heavy beard and bent posture under weight of an industry's esteem. Wallis saw threat of Muni forsaking “Paul Muni,” a charismatic brand with life left in it. Trouble was Muni wanting no part of things he had done before, thus firm and final no to High Sierra, being a gangster part, him foresworn not to be that again. The Sea Wolf was also offered, Muni in something akin to energy and aggression of old, but again he’d pass, Edward G. Robinson doing Wolf Larson and thriving (Wallis: “Muni … was extremely critical of the roles offered him, and turned down part after part”). Muni eventually left Warners by mutual consent after a last few for them went into red, the star blamed in part for overruns on Juarez. A vogue for historicals seemed over, and maybe Muni with them.

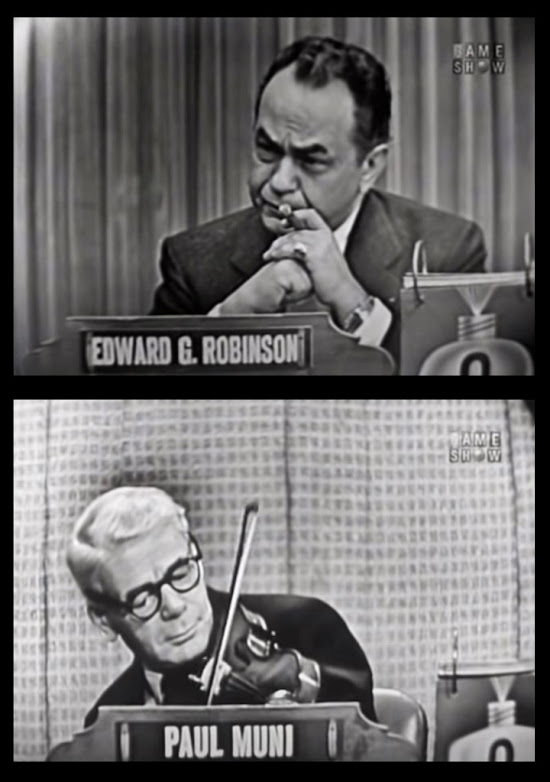

Robinson had gone a similar route and knew it, referring later to Muni as “my most potent competition. He played Pasteur and Zola; I could have. I played Ehrlich and Reuter; he could have. The Brothers Warner regarded us as two sides of a coin and did not hesitate to exploit the situation.” Robinson was flexible where Muni had not been, E.G. mixing character tries with what his mob expected from “Edward G. Robinson,” investing in safe stock to keep taut a lifeline (Ehrlich and Reuter both lost money). The 40’s saw Robinson broadening his brand further, triumphs in Double Indemnity (a support role, but the picture could not have done without him), Scarlet Street (a milquetoast, but murderous where pushed), ganging it up for laughs (Larceny, Inc.) or being hardest bark (Key Largo). HUAC weight and domestic collapse put Robinson in what he’d call “B’s,” but how he elevated them … Vice Squad, Black Tuesday, even a trifle like Big Leaguer. Paul Muni opted mostly for the stage, did a welcome reprise on gangsterism for half of dual role he had in Angel On My Shoulder, which in 1946 showed what might have been had Muni played ball with genre formula. Like virtually all of past/present Hollywood in the 50’s, Robinson and Muni guested (separately) on What’s My Line, Eddie brisk and chatty, Muni reserved and giving answers via awkward device of playing “Yes, We Have No Bananas” on a violin he brought, a gesture to counter those who claimed he had no sense of humor. There are books on Robinson, one by himself, and excellent. Michael Druxman wrote on the life and films of Muni, revised and reprinted by Bear Manor in 2016.

4 Comments:

Muni was usually pretty stagey (maybe hammy) in movies, while Robinson knew exactly how to act for the camera. I watch Muni movies just to see what he's like, but Robinson because I know he'll deliver a great performance.

Muni's appearance on "What's My Line" could have been interesting, but is irritating to no end, like Harpo Marx on "Person to Person". Just talk, for God's sakes!

Angela Lansbury once talked about preparing to do "Murder She Wrote". She was advised to play the character as close to herself as possible, because if the show lasted several seasons it was going to be punishing enough without the extra concentration. Maybe the same thinking guided studio contract stars.

In recent years, superhero franchises have become refuges for aging leading men. They sign on as mentors and villains, providing star power when the actual heroes -- even the ones with impressive resumes -- tend to be unknown to mass audiences (and more willing to sign multi-picture contracts). When Robert Redford turns up as an idealistic politician or Jack Nicholson as the Joker, they deliver not just a star turn but all the heft of their career personas.

Aging leading ladies have it tougher, as always. As Yvonne De Carlo's character sang in "Follies": "First you're another sloe-eyed vamp. Then someone's mother. Then you're camp." These days they tend to score juicier roles in smaller projects: plays, indie films, and television.

Once again....

"Who's Paul Muni?" "Get me Paul Muni!" "Get me a young Paul Muni." "Who's Paul Muni?"

-- the robot

By all accounts I’ve read (or heard; Louise Rainer in a TCM interview was VERY clear) it seems NOBODY liked working with Mr. Muni.

But to my point, who’s in the header photo? Buster Crabbe and Betty Grable?

Post a Comment

<< Home