A Voice To Break Out Of The Wilderness

Deems Taylor Makes Classical Music For Millions

Do any of us still evangelize for old film? Not me. Whatever civilian disdains my Devil Bat can eat cake, or dab on Doctor Carruthers’ shave lotion. There is forlornness to people who preach for any art, as it seems always a hopeless cause. I’ve done it on behalf of what some call “classics,” but you all know what work that can be, and how seldom it is rewarded. List of those paid to do what they love is short as a boxer dog’s tail. One who did cash checks for spreading joy of music past was Deems Taylor. He spent much of a twentieth century making the case for classical, on radio, in person, as Fantasia spokesman. He also wrote books, opera, symphonies of his own. Taylor was of sort not born anymore, or else our world is no longer such place as will accommodate a Deems Taylor, or anyone of renaissance bent like he had. This all-round intellect who sat at the Algonquin Table composed music good as any of latter-day who tried, Taylor blessed by one-of-us quality that made him easy to listen to and laugh with, secret to his mainstream success being humor to break barriers between long hair music and crewcuts that chose generally to ignore it. Taylor took away intimidation factor that kept Great Music on margins of public acceptance. If we had him out there on behalf of classic film, there’d be a lot more average Joes and Janes in thrall of what is vintage. So has movie fandom had a Deems Taylor to gather flocks? Robert Osborne was close, if confined to TCM. Taylor got seen/heard everywhere. And he made the case for movies too, having wrote a first Pictorial History (in 1943) to cover beginnings, and forward, to then-present. Revisions, enlargements, were constant. A Pictorial History of the Movies was one, if not the, key volume to set generations upon path to picture love.

There were at least six printings that I know about, my copy from 1950 once owned by Josephine Dillon, the first Mrs. Clark Gable. Got it at nominal cost, had no idea it had been hers before opening to the flyleaf. But never mind, the discovery here is Deems Taylor, and how his outreach for music parallels effort others have tried in support of film. Movies were obviously of interest to Taylor, but not his priority as was music. Three books he wrote, Of Men and Music (1937), The Well-Tempered Listener (1940), and Music To My Ears (1949), summarize the author’s philosophy as to what makes classical music special, and how all should appreciate and enjoy it. Each volume derived from intermission talks he gave during symphonies broadcast between 1936 and 1943, his peak of exposure to a mass audience (ten million listeners weekly). Some of chapters came of columns he did for newspapers or popular magazines. His prose was aimed at an average reader, those not necessarily disposed toward classical music, but open-minded enough to trust Deems Taylor and let him guide listening choices. Of Men and Music and The Well-Tempered Listener stayed popular through the war, Armed Service Editions adapted from both, compact enough to fit in uniform pockets. The thing I discovered about these books is how easily content could plug in to arguments we would make for past film, proselytizing in many ways for a same cause, for what really is the difference between any of arts, so long as you’re committed to wider spreading of them? Deems Taylor spent a lifetime shaping his contention, using wit and relaxed style to make syrup go down smooth. Proponents for film can learn lots from this man.

|

| Deems Taylor and Date Turn Out for RKO Palace Premiere of Citizen Kane |

Taylor warned in the introduction to his first book “that many a potential music lover is frightened away by the solemnity of music’s devotees. They would make more converts if they would rise from their knees.” Amen to that insight, and yes, my knees buckle for spoilage of a Searchers or Vertigo, wings pulled off butterflies by shovel-dug solemnity. They once entertained, but now? Had I read present analysis of The Searchers, then seen it my first time in 1975, chances are good I would not have sat three hours at George Ashwell’s house trying to reason him out of a 16mm IB his confederate waltzed out of Warner Bros. Film Gallery. As to Vertigo, never mind. Was it ever worse off than when appointed Best, Finest, whatever? And who were those critics that so contaminated it with their votes? Nobody asked me to pick a best, though chances are I would have put Devil Bat on the ballot just to rock boats. Deems Taylor was always for staying out of deep dishes, those a ruin to joy for music much as film suffers from same. He fought snobbery wherever it raised an ugly puss. Someone laid a light diss on John Philip Sousa (“While it can hardly be said that John Philip Sousa was a great musician ---"), and on went Taylor gloves. He had been a fan from youth (with Sousa above at left), was chummy with the venerable bandsman: “For me, a great musician, like any other great artist, is one whose name identifies his work,” and Sousa certainly achieved that … still does. Many a past filmmaker is largely ignored, but with champions to keep at least a flicker of flame lit. "Ripe For Rediscovery" is a lead seen lots, applied to, say, William Witney (who made better program westerns?), Charley Chase (funny, or funnier, than the Big Three, or is it Big Four?), Ida Lupino as director, no, auteur. The list could go on. What is it about film fans that make a seeming one, or precious few, carry flags for the otherwise forgotten? Typical of movie “buffs” (hate that word) to identify with the marginalized. Did Deems Taylor see himself as a Sousa not properly applauded because he was too d---ed entertaining?

|

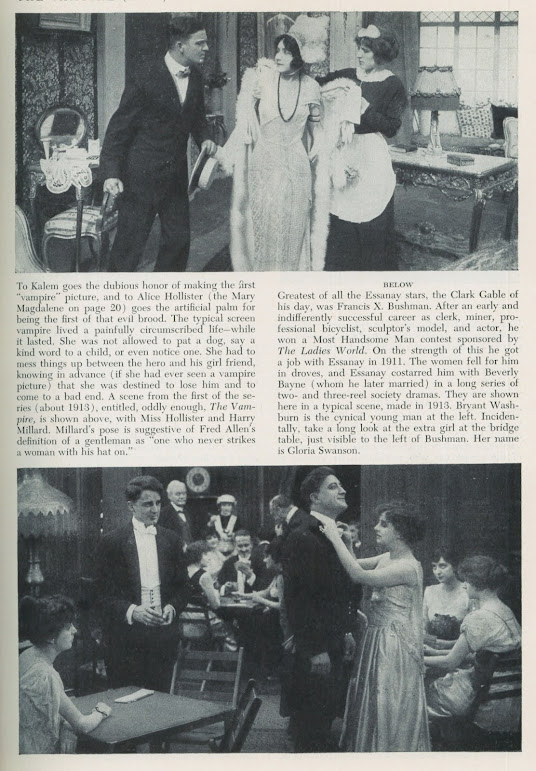

| This and Samples Below: Taylor Captions for A Pictorial History of the Movies |

Taylor alerted us more than once to fact music had not always played so well as for symphony broadcasts he hosted. Most did not dream (me neither), that “up to the very third quarter of the nineteenth century, a composer not only had to struggle to get his ideas down on paper, but then had to worry about getting a decent performance.” Organs for instance, electric by the 30’s and doing what players deigned, were once “blunderboxes,” as Billy Gilbert might call them, seldom sounding the way composers intended. Bach and Mozart created music for keyboards that, in their day, produced tone that was “pale, characterless tinkle.” Grand pianos were generations off, proper rendering of compositions heard only in the imagination of those who wrote them. Wind instruments were worse. Just getting it loud was a job called done. Eighteenth-century listeners “had no possible conception” of how Beethoven’s music should register. Taylor wanted modern audiences to appreciate how good they had it, what with instruments to realize all of values classical composers intended, but in their lifetimes never heard. Has digital raised presentation of film to a same acme? Apparati we now use could not have been imagined in analog circumstance, strides so considerable as to beggar belief. Having argued for/against “purity” of celluloid, I still side with what is newest (how long until 4K becomes a quaint past thing?). Had we been shown, twenty years ago, what is now possible to view in our homes, on top of access so ready, would we have called it a dream unattainable? How often have we said, It Can’t Get Better, then along comes something to prove, oh yes it can. Taylor’s telling of progress in music, at least improved means of performing it, harks by over eighty years to what we see now in delivery and consumption of movies.

|

| Two Who Tickled a Mainstream with Classics: Deems Taylor with Leopard Stokowski |

Radio was unique opportunity to popularize classical music, a best the country so far had. In 1937, four networks together averaged thirteen hours a week of live symphonic recital. These were for most part “sustaining” programs, meaning no sponsors, but broadcasters felt, at least claimed to feel, a “responsibility” in bringing culture to their nationwide listeners. Music begat prestige, and eventually corporations wanted in, thus General Motors Concerts (they had their own orchestra), with Ford close behind. CBS arranged with the New York Philharmonic to present Sunday performances, their midway intermission filled by Deems Taylor and entertaining background he supplied for selections offered. Half-point chats had been tried with others, none a click until Taylor took over (11/8/36), him seasoned at selling music to masses, having hosted the Chase and Sanborn Opera Guild (1934), getting six minutes as guest on Rudy Vallee’s Fleischmann Yeast Hour to “describe the evolution of different orchestral instruments” (Deems Taylor: A Biography, by James A. Pegolotti). Taylor as on-air emcee had style and wit, shared scoop on colorful long-ago composers all too human despite genius they were better known for. Taylor was an engaging TCM host before there was TCM. Folks on farms, far-flung midland outposts, discovered classical music and how Deems Taylor could help them enjoy it. No longer exclusive province of a metropolitan elite, now everyone could get cultivated. Some critics called Taylor “middlebrow.” Possibly they felt threatened by him. Not everyone was for democratizing the arts, particularly those who sought to keep finer things solely for themselves. Taylor shared facts few knew, like how greatest of composers were panned in their lifetimes by a critical establishment. Who would guess Mozart and Beethoven took licks, or realize Richard Wagner was a “Monster,” Taylor’s term to describe this most anti-social of creators.

Deems Taylor held strong opinions. He did not try pleasing everyone. Herewith an eye-opener from Of Men and Music: “The proportion of rubbish to great music that is being written today is what it has always been: about ninety percent.” This takes me aback. I could believe it’s true for now, but in the 30’s, let alone in Beethoven or Mozart’s time? But then that is my idea, or ideal, of varied Golden Eras. Taylor was no such enchanted. He would put most, if not all, of jazz among the ninety percent, it being “an epoch … out of which we are passing,” this as of the late 30’s when “its monotonous, reiterated underlying beat” was fast headed to obsolescence, or so Taylor thought. “Another romantic age of music is not far off,” the days of Weber and Schumann and Wagner “about to dawn again” (dream on, Deems). Taylor saw jazz as aberrant offspring of the Great War, “fear and grief” making us want to “get away from our emotions.” It is easy to read such as this and think only of how wrongheaded he was. Taylor lived long enough to realize as much for himself (d. 1966). But we would be wrong to assume that everyone except him embraced jazz and variants of it to come. There were cycles and fads to rise in my lifetime that I rejected then, and now. Am I mistaken just for being outnumbered? Taylor states his case, and much of it makes sense. And what if he is right about the ninety percent? Pass music a moment and ask yourself if 90% of movies, then or today, are rubbish. Check a list of every feature released in 1936 (at least 700). I would be almost afraid to, knowing I’d tote up a dozen or so Monograms and say, “Hey, what’s so bad about these? I think they're swell!” Chances are my 90% estimate would reverse the rubbish/good ones ratio. Watched yesterday, for example, Boris Karloff in The Man Who Changed His Mind. Would most put it among ninety percent? Very well. Line them up, I’ll fight ‘em one at a time.

Deems Taylor was not the first crusader for mass (good) music acceptance. There was Theodore Thomas of the previous century. He hailed from Germany, US-arrived at age ten, set forth early upon civilizing savages we were. His orchestra started east from New England to San Francisco, back again, then again, and again. Tours were exhausting, but he got known, extraordinarily loved, by a nation not yet overwhelmed by media. They literally hung off trees to hear Thomas play (his many outdoor events). It is safe to say, in fact many did say, that lives were changed by Thomas introducing them to beauty of sound they did not know existed. You could say that he gave America its culture, at least a first real opportunity to experience culture. Thomas said that “a man who did not know Shakespeare was to be pitied, but a man who did not understand Beethoven has not half lived his life.” Theodore Thomas’ mission was to put worthwhile concerts within reach of all people. His setting forth upon that goal just after close of the Civil War made for higher hills to climb, what with audiences given to beer, tobacco, and lively chat as accompany for music. They also liked polkas or a jig to wash down weight of classics, but at least they were exposed, and over time, took to Great Music mightily. In the end, however, Thomas realized that “neither children nor what are called ‘wage-workers’ were sufficiently advanced intellectually to be able to appreciate the class of music which was his specialty,” this as summed up by Mrs. Thomas when an older/wiser husband quit the road to form Chicago’s Symphony Orchestra, wealthy sponsors agreeing that quality music was appreciated best by “the most cultivated persons.”

|

| Deems Taylor and Daughter at Home in Stamford, Connecticut |

Deems Taylor called one of his chapters “Catching Them Young.” It deals with children as introduced to music very early in life, as in six months old. Saddest of grown folk are those who missed out during crucial window that was youth. I wish it meant something to me, they would tell Deems later. A popular tune I can understand and enjoy. But serious music --- anything you fellows would approve of --- sounds too mysterious and complicated to be any fun. Reminds me of an answer I'd get for offering to show someone a black-and-white movie, or worse, a silent movie. It is too late because chances are they were never exposed to such things before. Taylor thought you could raise any child to enjoy fine music. It worked with his daughter. I’m not convinced, however, that such devise would succeed using classic film. I more and more suspect that children grow to love movies only for discovering them on their own. The how might be as close as You Tube or a myriad of streaming services. Taylor said his little girl was hooked by age three, this after concerted effort on his part to expose her to his idea of outstanding music. Not sure I would have enjoyed being his kid. Had someone tried indoctrinating me to classic films, would I have run in another direction? I tend to go badly against the grain as it is. Maybe a reason I so embraced old movies was that nobody endorsed or recommended them to me. Query to readership: Did you come by your interest through someone’s tutelage, or was embrace of films a result of chance, sheer inadvertence?

Finally, Taylor’s crusade to bring American audiences to Grand Opera. Here was reach at stars seemingly beyond his or anyone’s grasp. First were language barriers insurmountable. Operas not being in English made them inaccessible to overwhelming most. Taylor was a realist and friend to common men, latter which could not be expected to sit three hours for a pageant they understood not a syllable of. He pointed out (“What’s Wrong With Opera” chapter in Of Men and Music) that in Europe, they freely translate operas to regional languages, thus Italian originals performed in German for German audiences, and vice versa, habit observed since opera began. Why not over here, Taylor asks? He guesses at reason … we don’t have the resources or wherewithal to do it right, and purists would not tolerate outcome if we did. Meanwhile, we continue to fall asleep or walk out on operas to this day (is this still the case eighty-five years after Taylor spoke his piece?). Hard to fake enjoyment of something you can’t make sense of. Remember in San Francisco when “Blackie Norton” goes to the “Tivoli Opera House” to shut down “Mary Blake’s” singing debut? Blackie watches a few minutes of the recital and is captivated. Even thickhead Harold Huber converts (Gee boss, she’s great), upshot being they back off to let the show go on. Was anyone in real life won over so sudden by opera? If yes, MGM would have done more than just excerpts with Jeanette MacDonald, but then of course they sort of did with her “Operetta” series co-starring Nelson Eddy.

Deems Taylor does not mention movie operettas at all in his books. Did he regard them as bastard offshoots of legitimate opera? Yet it is snobs and highbrows he targets in much of text, so surely Taylor saw operettas as an overall good thing, movies bringing us closest as a group to an opera format we would never accept other than distilled. I confess to having seen but three operas, one each with Lon Chaney, Claude Rains, and Herbert Lom. Some joke … but Deems Taylor might sympathize with a dunce like me. It would be Grand to like Opera if we truly knew what was going on. Taylor struggles with this issue, wishes things could be different, strived to make it so, but like Theodore Thomas in the end, knowing it was not to be, at least in his lifetime. Under heading of Believe It Or Not, he was hired in 1934 by Paramount (pal William LeBaron) to help produce a Grand Opera for film, not a novelty short, a full feature. Never came to fruition, but fact it was even floated was anomaly enough. Speaking of lifetimes, Taylor’s and our own, I looked to see if New York’s Metropolitan Opera House is still there and operational. Relax all, as answer is yes (albeit in a new location since 1966). But here’s what stunned me: There are 125 opera houses in the United States right now. Deems Taylor would not have believed it, as only two were extant (“permanent producing opera companies,” as he put it) during the 30’s, the Metropolitan in Gotham, and the Chicago Civic Opera. I’m resigned enough to us going downhill culturally for a thing like 125 to be all kinds of unexpected, so much so as to pledge being there opening night when northwest North Carolina gets a first Grand site all its own (how about they retrofit the Liberty?).

18 Comments:

Query to readership: Did you come by your interest through someone’s tutelage, or was embrace of films a result of chance, sheer inadvertence?

Sheer inadvertence. Local television was running Our Gang and Three Stooges shorts, and I enjoyed seeing the old cars. This got me reading the copyright notices on the credits, to find out how old the pictures (and the cars) were. This of course was well before anyone could find filmographies of these shorts, so all I could do at a very young age was to try to find the evidence on the films themselves. Continued exposure to old movies made me a fan. (By age 14 I was working at an antique-auto museum as the film librarian, so I had the best of both worlds.)

I think the major barrier keeping old movies from the American public is that local stations no longer maintain their own film libraries. Most stations are now affiliated with cable networks, which dictate the programming and the scheduling. How many hundreds of old theatrical features and shorts were abandoned when these stations shut down their film rooms? I don't know how many TV stations are still self-sufficient, but I applaud their independence. (I understand that one station still runs C & C Television prints from the 1950s!)

My current interest in film can be ascribed to the rise of home cinema; I started purchasing movies on VHS tape as soon as the prices for those became less than what was being charged for a CD of music, around 1990 or so. I figured two hours of A-list Hollywood for 20 bucks was a better deal, giving me more bang for my entertainment buck, than 70 minutes of music. Back then, I couldn't understand how a manufactured, pre-recorded VHS tape with all of its moving parts could be cheaper to buy than a CD disc of recorded audio material stamped or burned in a press - it turns out the CD guys back then were price-fixing, but that's another story.

Going to the movies was never a regular activity in my childhood, so whatever exposure to film I had then would have been from B&W TV, the titles watched being strongly influenced or entirely determined by what my older siblings wanted to watch - I dimly remember scary movies hosted by a "Sir Ghastly" or some such on Saturday afternoons; but I was also exposed to movies insofar as photography was an early hobby of mine and, via the photo club in junior high, I learned all about the tech of photography, including film tech - though I rather disliked working with the latter as I couldn't develop the shot film myself in the darkroom we were using.

That camera activity did get me involved with those who would (and did ) stage dramas for the film camera, so the whole experience did give me a glimpse or taste of what went into the technical side of film production; this led to me, some years later, taking a film course as a "spare" in college, which turned me on to some specific older movies and names of the people who made them; and that, some years later, gave me something to base my VHS purchases on. I suppose my early experiences with the technology of the camera grounds my lifelong love of the use of special photographic effects in movies.

I guess you could say that I came to the movies through the camera, not through the lobby or the stage door.

DT was not the first to hold to a certain percentage.

Interviewer: "Isn't it true that 90% of science fiction is mediocre?"

Ted Sturgeon: "Yes, but 90% of EVERYTHING is mediocre."

I think kids are collectors by nature. If something is part of a series -- a comic, a trading card, a toy accessory, a series book -- a kid will want to Collect Them All, either by experience or ownership. Often the trait endures, in adults who binge watch a complete TV series, snap up every volume by a genre author (or in extreme cases, whole genres), or purchase kitsch explicitly framed as Collectibles.

I think my gateway was series films. I wanted to see ALL the Universal monsters, ALL the Stooges shorts, even ALL the Shirley Temples. The franchise mentality now drives the industry. Everybody is trying for the next Harry Potter or Marvel, playing on your instinct to Collect Them All rather than consider each new one-of-a-kind movie. Today I'm a near-completist, filling shelves not only with popcorn classics but piles of second feature sets (Jungle Jim six pack!), cartoon compilations and pretty much all the short subjects I can find.

I got into silent comedy as a kid because you could find it in 8mm at the library, or even buy it from Blackhawk Films. There were a few outlets on TV, such as "The Toy That Grew Up" and Robert Youngson features. There was also the feeling that these were made by people and not mysterious technicians in big complicated studios using grownup secrets. You could see the hand-made mechanics of staging, performing, editing, etc. You were tempted to take the 8mm camera and make one yourself, usually ending up with a trick film of goofy friends appearing and disappearing in the driveway.

Lately my fantasy is to set up a digital projector in the patio and lure grown-up neighbors over for two-reelers. With proper appetizers and beverages I think I can ease them into silents more easily than children.

Cameras which use actual film stock and produce negative images as an intermediate step in the production of images, of the type which first interested me in motion pictures, have become as obsolete as Saturday afternoon monster movie TV programming along with their costumed hosts; and while I was listening to some opera lately on my good old stereo ( and I'm not really an opera fan, but I do consciously try to "expand my horizons" from time to time), I was told that opera is "an obsolete form of entertainment". I have to agree - fresh and popular operas are rare indeed, while I think in the USA today the Broadway show has become the true 21st Century social analog of what the opera was to 19th Century Europe.

Perhaps the number of active opera houses in the US is explainable partly by people wanting to experience something different when they get out and about for an evening ( or an afternoon ) since the movie-going experience has become affordably and entirely replicable in the privacy of people's homes. Maybe it's like restaurant meals - when people go out they want something different from what they can get at home.

Some decades ago I was a season ticket holder for Opera San Jose for a few seasons. Back then it was a scrappy offshoot of a college program, shepherded by a retired Metropolitan star and drawing national attention for showcasing new talents. Today its home is the California Theatre, a vaudeville house that became a movie palace. I saw "101 Dalmatians" there when it was called the Fox Theater.

They had supertitles roughly translating the lyrics, a bit like a stock ticker over the stage. Still, you were urged to read the program synopsis and/or English libretto beforehand, which to my mind knocked much of the drama out of it. What was left was a very theatrical concert, and sometimes that was enough, but I was (and am) too attached to the notion of following characters through a plot.

I recall "La Boheme", staged in the compact Montgomery Theater which also hosted straight plays, children's musicals, and lectures. The publicity emphasized that this was a rare chance to see the starving students played by young, svelte singers. Also, the garret set was only slightly larger than an actual garret. Being a philistine, my favorite was "The Merry Widow". Strictly speaking, it was operetta -- there was clever spoken dialogue and the lyrics were in English. Also, a very pretty soprano not only sang but led a can can.

I drifted away, sticking to regular theater (mostly musicals) and the local Gilbert & Sullivan society. G&S operettas are highly accessible, because surprisingly little of the comedy dates. The movie "Pirates of Penzance" with Kevin Kline and Linda Rondstadt works too hard to be cute, but it's mostly a lot of fun. And what's fun is what Gilbert put there ages ago.

I guess my intro to old movies were the Stooges, too. But it was that great series "Hollywood and the Stars" that convinced me I lived decades earlier. All those '20s and '30s movies seemed more familiar than anything that was around then. It was disconcerting, considering none of my friends felt the same way. And I think I enjoy Joseph Cotten as much as I do because he was the series' narrator.

I introduced my daughter to Laurel & Hardy when she was 5, and she LOVED them. From there, it was all kinds of old b&w movies -- her favorites were Rathbone Sherlock Holmes, Peter Lorre, Lionel Barrymore... From the age of 5 til she went to college, she saw dozens upon dozens of oldies, and enjoyed them all. Except Charlie Chan and the Marx Brothers.

That Deems Taylor book was the first book about movies I ever checked out from the library -- same edition, too.

I forgot to mention something else. For a brief time in my mid-30s I attended operas that were sung in English. New ones like "Nixon in China", "1000 Airplanes on the Roof" and one whose title escapes me which was about Charles Manson. I don't think the latter has been revived. But the best was "Rigoletto", which was updated to New York's criminal underworld of the 1950s.

And as for Shakespeare, I find the dialogue easier to understand when it's updated, like Ian McKellan's "Henry V", which took place in a fictional fascist Britain of the 1930s. My father, who was no intellectual, really enjoyed the 1960s "Hamlet" on Broadway,which Richard Burton and the cast performed in regular street clothes. Just present the play in settings people are familiar with, and they'll likely to enjoy it.

The updated Shakespeare with Ian McKellen was RICHARD III, not HENRY V.

I was raised being taken to the opera at the Colón theater in Buenos Aires; I have never found a better place to see them. It took me time, since I started as a child when I was still learning to read, but eventually I learned to understand and enjoy it. My dad preferred instrumental classical music and I used to listen to a lot of that on public radio when I had to spend long times using my car, but I stopped after figuring that they were basically rotating the same "popular" titles instead of offering the variety I would expect.

In Argentina, I never needed a Deems Taylor simply because the broadcasting industry was originally born on August 27, 1920, with the intention to bring home live classical music shows. That soon changed to popular music yet, up until the end of the 1980s all but a few of the opera performances from the Colon theater were broadcasted live on the radio.

That ended around the 90s when these live shows shrank to a very minimum, switching from AM to FM stations, and the number of stations carrying them reduced drastically.

Movie are not a good way to enjoy classical music performances and opera, operetta, or zarzuela either. Musical segments on film most of the time seem very artificial and fabricated that can actually spoil a movie. They need to be experienced live, which is why the worked for many decades on radio. Television is welcomed, but it never seems to be fully fitted for it, despite many fine examples that have been recorded for years and that can be seen on YouTube.

I'd write here and tell you all how I got into the love and collecting of old movies, but I've already done approximately six hours on that with Glenn Mitchell and Hooman Mehren in two zoom webinars on the Silent Comedy Mafia website. here are the links:

http://bit.ly/ComedyCollecting

https://bit.ly/ComedyCollecting2BOX

Those should answer the question.

RICHARD M ROBERTS

A fascinating post about a fascinating man. Thanks.

Always estimable Craig Reardon has some remarks about music (Part One):

Hi,

Well, you have outdone yourself with your lengthy and perspicacious column about Deems Taylor which expands in many directions. One of the best things I've read that you've done, although I rank all of them pretty high, so we're talking a couple of extra percentage points above 100, here.

I've loved music all my life and I encounter various thoughts here all of which register. My dad loved music and had a fairly extensive collection of the brand new 'lp' records from the time I was born (in 1953), and I grew up hearing them being played every weekend, which presented him with his best opportunity of course to put them on and listen to them. He didn't usually plant himself in front of his record player--in those years, usually part of a console, though dad was enough of an enthusiast to eventually acquire a separate, much-better-than-usual record player, and a "hi-fi" system to play back what it read with its tonearm--but rather went about his other routines with music 'in the air'. As per your theme, he did not have too many titles in his collection which could even loosely be termed 'classical', but I remember he did have a terrific early lp version (versus of course even earlier multi-disc albums, which required multi-discs when they were to be played at a speedy 78 rpm, vs 33!) of George Gershwin's popular concert pieces "Rhapsody in Blue" and "An American in Paris", conducted in a brisk and expert way by Paul Whiteman and "His Orchestra". The players deliver a performance which is so nimble and so good that you'd have to call it 'perfect'. There were plenty of musicians in the 20th century sufficient to serve the movie studios and the recording studios with excellent playing, almost astonishing when you think of how challenging a lot of that music was to perform, whatever highbrow critics may have thought of it otherwise. And yes, the tyranny of the 'expert' has been defeated in part by simple indifference. That's not the perfect solution, but anything to pull some of these bastards off their own self-appointed perches is O.K. by me. I've seen many figures who labored in what used to be labeled 'commercial' applications of various arts such as painting, writing, music, and certainly the movies, never much more than beneath the contempt of the priests of high culture, gradually elevated to a level where we need not be made to feel embarrassed to call them what they were, great talents--and the former terrorists who could make or break reputations of people a thousand times more worthy than they are forgotten or unheeded, and certainly also dead. You know, Sibelius--also assaulted by these pests when young, due to his own unconventional style in 'classical' music--was quoted as having wonderfully responded to these guys by saying, "Nobody ever erected a statue to a critic". Touche, Jean! (Though now there's a rather badly done one to memorialize film critic Roger Ebert, though I forget where--that's actually O.K. by me as Ebert had a pretty egalitarian style and outlook, vs WAY too many of his ilk. And, not bad taste, in my opinion.) And then there was the remark made by a classical composer who primarily focused on writing art songs, and I'm embarrassed that his name isn't on the tip of my tongue--I'll probably remember it AFTER I've sent this!--but who was quoted as having written a letter to a newspaper critic who'd insulted his work, "Your review is presently in front of me. In another second, however, it will be behind me." I mean...top that.

Part Two from Craig Reardon:

I also have to smile and agree with your argument on the other side, using famous films like "The Searchers" and "Vertigo" as good examples. Two entertaining masterpieces of entertainment, engrossing and the acme of each one's director's style and type of subject matter of preference. Hitchcock went on the record with his admirer (and I will speak heresy to add, I think his inferior) Francois Truffaut, saying he did that particular film because he was intrigued by the idea of a man being obsessed by the idea of "going to bed with a [dead woman]". Wow! Pretty kinky, there. I saw "Vertigo" on NBC network in the mid-'60s--and in B&W on our family TV! Anyone seeing it today can imagine what was missing not seeing it in color. But I was transfixed by Kim Novak as both herself, a talented (and never given her full due, and that's also the fault of critics) and beautiful apparition, filling in for me for a handful of lovely little girls I'd been similarly mesmerized by at school as a youngster, spellbound but doomed as far as any hope of communicating my feelings for them to them.

This was my linkage to the movie, versus say Hitchcock's stated interest! But, not all that far apart. The common element was and remains an interest, a fascination, that is so persistent and runs so deep that it becomes idealization and ultimately obsession. And without any outlet, any real connection, obsession in this context is not a good thing. It certainly doesn't turn out well for Stewart, but that's due to the mechanics of the plot, with its frankly implausible murder scheme which everybody who dislikes the film immediately pounces upon, yet meant literally nothing to Hitchcock more than one of his now-famous flimsy pretexts he'd dismiss by his story about a "MacGuffin". That's the story that ends in admitting there ain't no such thing! I still have a good friend, very smart, who hates "Vertigo"--because, he says the idea a guy could or ever would go to that kind of effort to concoct such a ridiculous back story and then have to depend upon hooking his hapless acquaintance, late of the police force, into following his stand-in for his wife--already dispatched with a broken neck--up a vertiginous (sorry! But that's where the brilliant title for the movie makes itself clear) staircase only so far, so that he can shove his real wife, identical in appearance, out a convenient floor-to-ceiling window up in the bell tower to fall a couple stories to the tile roof below--is so ridiculous and farcical that it just ruins the entire movie. I laugh to myself whenever he repeats this because that element is literally the least interesting or germane to enjoying this film, for me, that I can dismiss it effortlessly. Me? I'm hooked from the beginning, by the dual talents of Bernard Herrmann and Saul Bass.

I think it's fair to credit Hitchcock already at this point because by that time he'd become not only a director with the ability to pick his projects, but also his own producer, able to pick his collaborators, which he did at this point in his career with great astuteness. The melodramatic chase at the beginning with the Hitchcock focus on putting you, the audience of one, into the mind and sharing the viewpoint of his protagonist, watching a colleague trying to help 'you' from a terrifying predicament slip and fall many stories to his terrible death, makes the point as well as anything that heights can be scary and fatal. This isn't Hitchcock trying to scapegoat his coming murder plot. This to me is the director making a gesture toward justifying it. I have no doubt his focus was always on the tremendous desire this detective who narrowly escapes death from a fall develops for this mystery woman, and then of course his renewed and even more oddly grateful and disturbing desire for her 'double', who only he initially fails to reason is the very same person.

Part Three from Craig Reardon:

But meanwhile, Hitchcock is not going to short change his audience by failing to give them an unforgettable opener to his picture! And he fills in with scenes of his own type of immaculate moviemaking rife with atmosphere and strangeness between this opening shocker and the 'first' death of Novak's character. For me, the tougher portion is his obnoxious but still, in spite of modern criticism, pathetic and sad urgency in trying to restore the first woman by means of transforming one who 'resembles' her into her almost exact image. It appears that modern sensibilities find this entirely hateful. I don't. I think what he does to the woman is awful, but I think what he's gone through and what he's still going through is human and profound. I think that what makes this film hang in there is this depth of feeling. When the character of Judy, who I admit is an equally implausible sort of girl to have been able impersonate the sophisticated Madeleine, but nonetheless when she too dies identically, and partly due to his own fault, the image of this ruined human being suddenly oblivious to height, looking down at her body out of frame is one of the great, devastating final images in movies. Particularly from a director who would say things like, "Other people make films which are a slice of life; mine are slices of cake."

I like your mention of the fact that Deems Taylor championed John Phillip Sousa against familiar condescension from the musical priests of his day. I'm very fond of the biographical film about Sousa from 20th Century-Fox, made in the final months before the studio converted 100% to CinemaScope, and brilliantly if obviously titled "Stars and Stripes Forever". It's obviously a movie-type biography designed to entertain versus observe all the p's and q's of reality. By the end, when Sousa 'premieres' his latest piece dedicated to the military, being the title of the picture as well, your hairs stand to attention, military style! The performance by the great Fox orchestra under Alfred Newman cannot be bettered. Then we're presented with a beautiful montage of all the armed services marching in review in various locations, and a ghost over of the talented Clifton Webb as Sousa marching with them. I can't say exactly why, but I think regardless of your politics, this imagery and this music brings forth a surge of the best kind of patriotism and pride, and yes gratitude. That's no mean feat, and Sousa's music is the underpinning. What Taylor was saying, I think, is don't go to a work of art looking to contextualize and rate it--surrender to it and try to come up to its own standard.

Craig

'Vertigo' is all about letting go.

Scotty clings to the roof's edge to save his life at the outset of the film, and the experience drills into him the fact that to let go is literally deadly, and he learns that lesson all too well, he becomes mentally unbalanced; so later in the film, his failing to let go of the memory of Madeleine ( as an aside, if they did hook up as a couple, they could be called "Scotty & Maddy" ) brings on its own tragedy. Even letting go of his "old college buddy Gavin" would have been much better for Scotty than what transpires as a result of him trying to revive that acquaintance.

Knowing when to let go, and when to hang on, has long been a primary concern of human beings as we scamper through, around and over our world - it's a physical, primate thing, as we do have hands and use them all the time. Hitchcock's film seeks to extend that physical concern into the emotional world.

So for me, 'Vertigo' is a film about hanging on and letting go, and how failing to do either at the appropriate time can go horribly wrong - and the film plays on the tension and suspense ( suspended up in the air) leading up to the choice of whether or not to let go.

For me, the entire film is like a coded warning about nostalgia itself, about how clinging to past emotions doesn't work like physically clinging to a ledge on a high building. The film is saying that letting go of the past, and of the dead, is necessary to go on living. Scotty needed to let go, and the film shows what happened when he didn't.

Dan Mercer considers Deems Taylor and his own appreciation for classical music:

You do go down untrodden paths, be it mountain train excursions, Harry Langdon, or vaudeville. It is well that you do, though, for if the paths be untended and overgrown, it is rarely for want of the qualities that gain our interest, but rather for the distractions of the moment.

Now it is Deems Taylor. A couple of years ago, I gave as a present to a friend a copy of Edna St. Vincent Millay’s libretto to Taylor’s opera, “The King’s Henchmen.” It was quite popular in its time but almost entirely forgotten now. Even with nearly everything available on the web, I found virtually nothing that did justice to it. There is this recording by Lawrence Tibbett, however, which suggests a work of some charm and musicality:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lUWvEqjqa2g

I also found an unnamed tone poem by Taylor that is even better and very evocative of a contemplative and romantic perspective:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G88Rk_NYH2o

My own acquaintance with him was like that of so many others these days, through Disney’s “Fantasia.” It was the re-release in the late seventies of what was purportedly a restored version; or at least modern stereo was used to simulate the effect of Fantasound. What made it especially impressive was its being shown on a truly big screen, that of the Moorestown Plaza theater, which had one auditorium seating 2,800 people. For comparison, it now has nine screening rooms carved out of the same space.

I found Taylor’s comments concerning the intentions of the composers of the various pieces entirely sensible. If anything, it highlighted how extraordinary “Fantasia” was and its seriousness of purpose. Much later, however, I read a contemporary review by Otis Ferguson for “The New Republic.” Ferguson wrote of his love of classical music and was somewhat askance at the “hollow fakery” of the film, yet confessed that was nonetheless “one of the strange and beautiful things that have happened in the world.” As for Taylor, though, he had little patience with his appearance or remarks and turned away from him with relief. I believe that Ferguson made a valid point, in that such narration was unnecessary and an intrusion, but given the unfamiliarity of the audience with the idealization represented by the music and how this was transcribed by the animation, if it had to be done at all, it could hardly have been done better.

As you suggest, Taylor’s prominence in his time was merited, such that we would benefit if we were to approach the arts as he did, not upon bended knee, but as the expression of truth and beauty as they should be understood and made a part of our lives; that is, by men walking upright into the sunlight.

Great stuff as always.

I STILL don't understand why the latest blu ray of Fantasia doesnt have any segments with Deems Taylor's real voice.

it has been explained to me 900 times and I still don't understand why my laserdisc and VHS have his original voice...but the blu ray has someone imitating his voice instead. For the entire film, not just the "restored" sequences.

As for "how I was exposed to classic films". Thats easy. Severe Insomnia throughout my adolescence. So it was Universal horrors on channel 45 and RKO movies (Astaire/Rogers quite frequently) on Channel 13. At 1am. And a classic film fan was born.

Post a Comment

<< Home