Boris Karloff Presents ...

Stories To Go Bump In The Dark

Occasion was Wally and Beaver wanting to go downtown for a horror combo, their having enjoyed Hot Rod Cuties and Rope Justice the previous week. Leave It To Beaver writers clearly had no respect for Saturday stuff as followed by children in the late 50’s, but a line of Ward’s stuck with me as what a then-generation of fathers had themselves grown up on. Ward at least understands basis for his boy’s enthusiasm, his having “seen Dracula four times and had a subscription to Weird Tales magazine” during long past youth. The line struck me for what it revealed not only of fictional Ward Cleaver, but also series staff. So there were grown men in the fifties and early sixties who once enjoyed chiller movies and scary mags. And here we thought such decay was our generation's alone. Someone went to Dracula in 1931, in fact, throngs did. My father even admitted to having been there at advanced age of twenty-four when surely vampires would not impress him unduly. I grew up assuming no grown-up but Forrest Ackerman cared about monsters. Others thought them silly, regressive, a bad influence. I might have looked askance upon any adult professing to like horror films. Hollywood did not help by making chillers childish and silly. Exception of The Haunting in 1963 was for me like eating off fine China at my aunt’s house on Thanksgiving. Surely a few past adolescence saw The Haunting too, but none acknowledged it to me. Horror could enter however, through a back door that was literature, enjoyment to be had in private, stepped up from pulp that once was Weird Tales and like kind. To this came Boris Karloff as surface Bogey Man, but erudite scholar beneath, dispensing spooky but tasteful tales we’d not be ashamed to be caught reading.

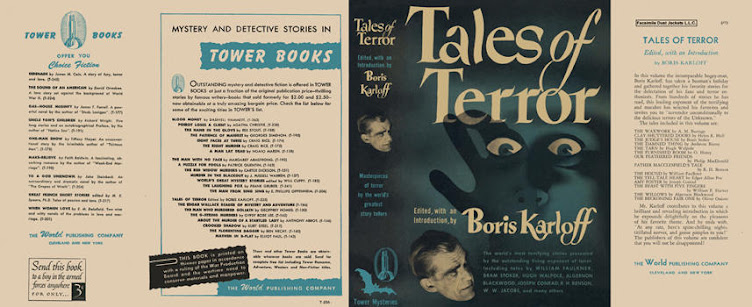

Karloff was a cultivated man. He attended public schools in England, King’s College in London. These I suspect offered more rigorous instruction than could be had from Ivy Leagues selling degrees today. Karloff enjoyed the company of others who read prodigious as he, among them Edmund Speare, an editor for Knopf, whose The World’s Great Short Stories --- Masterpieces of American, English, and Continental Literature had been a considerable success when first published in August 1942, five more printings by June 1945. It occurred to Speare that a collection of goose-bumpers, so-called Tales of Terror, might click if vetted by Sultan of Scares Karloff, credited as editor and penning an introduction in addition to helping with story selection. He and Speare drew on material dating from the nineteenth century forward. There was Poe, Joseph Conrad, Faulkner, Bram Stoker, plus others of less renown, each thought by the pair to merit inclusion. Fourteen tales in all, which I read because Boris Karloff recommended I read, a strongest of incentives (“Full marks,” he might say upon my completion --- why did I not curry such favor with instructors at school?). Karloff as connoisseur of fright fiction was known to me far back as when a series of comic books used his name and image for monthly cover art and as “host” to open stories. Tales of Terror appeared in 1943, obviously early for me, so a copy was latter-day got, distinctly second-hand and sans a dustjacket, but for a low price. The Karloff intro at five plus pages reminded me that here was a man seasoned in the arts and a more than capable guide to fiction worth reading. The yarns being short meant gratification was had within thirty to forty-five minutes, a best kind of reading for one restless as I sometimes can be (check e-mail, investigate noise in the carport, what makes the neighbor dog keep barking?).

If you couldn’t take Karloff word as to what chills, then no one was reliable. My second-hand Tales of Terror arrived by mail, worse for the wear, pulpwood paper the necessary wartime option, as it would remain for Karloff's next anthology, As The Darkness Falls (1946). Add intervening years and pages flake apart just for looking at them too hard. I made a pencil note and the point sank right through the yellowed parchment. A lot of copies must have sold because both books are common on used terms. With a dust cover, however, let alone intact and unworn, cost can run higher. I went to Facsimile Dust Jackets LLC for a faithful reproduction of what wrapped both books when new. You can’t tell them from originals, an enhancement for my time reading. Editor Karloff says he gave “help in compiling” the collection, but “major job of reading” went to Speare. Still, “stories literally rained on me by the hundreds," recalled Karloff, "for weeks on end I regaled myself at this wonderful feast and was a mass of delicious goose pimples.” Karloff had wit himself as a writer, enjoyed authority to pick out the best and weed out the rest, a “fine frenzy of egomania” he wished could “last forever.” The process took place during Karloff’s road tour for Arsenic and Old Lace, as he refers to conference and correspondence with Speare through a period of constant travel. Timing was perfect for Tales and Darkness, as Karloff had never enjoyed such prestige as he would for the extensive run of Arsenic. I bet every library and book stall in the country snatched up these volumes soon as they came available.

|

| Panelists on Information Please: John Kieran, Franklin P. Adams, Boris Karloff, and Oscar Levant |

Karloff as editor and interlocuter for these stories made sense, his intellect familiar to listeners of Information Please, a radio panel where never-easy questions were posed to regulars and guests, BK frequent among latter. I played an episode (2-20-42) where John Carradine joined the group, he and Karloff visiting “monsters” whose acumen was put to the test. As both occasionally recite from Shakespeare, Grimm Fairy Tales, Arabian Nights, or Joseph Conrad (a writer pet of Karloff’s), it seems unlikely they were briefed as to mere answers in advance, since their responses often amount to spontaneous performance. How humbling to hear those of past time who were broadly educated, knew folklore, the classics. A lot of radio was frivolous, not shows like this. You’d think Information Please was a sustaining program, but then comes the Lucky Strike announcer and we know theirs was a mainstream audience. Karloff had definite ideas as to what made scary storytelling, distinction between “horror” (repels) and “terror” (un-eases) one he would often point out to interviewers. His was a thinking man’s appreciation for fiction dealt dark. As would later be the case with Christopher Lee, Karloff was fascinated by chilling aspects of literature, realized his own contributions on film were seldom what he hoped for, but ray of hope did come with his three for Val Lewton at RKO, who Karloff credited with “rescuing him from the living dead, and restored, so to speak, his soul.” Must have pained Karloff to perform in what he knew were inferior films, even if final tally did reveal worthy work, law of averages to permit a fair number turning out well and sometimes exceptional.

Karloff maintained that power of suggestion was what frightened best, and yes, some of writers in the anthologies served this end nicely. Much of text on the other hand goes way more explicit than movies could dare in the forties, graphically descriptive of mayhem, rotted corpses, varied “putrescence” let loose to prey on man. Radio dramas in which Karloff appeared were often as morbid. Did parents oblige Junior to switch off sets where graves were dug too deep? Separate picture from words and you’d go places a visual image was forbade to enter. We could argue that rawest chilling Karloff or anyone did was through a microphone, broadcast censorship laxer on horror than oversteps re sex. Did rawest meat on radio come courtesy chill broadcasts such as Karloff and kin supplied? License at least for a while extended to comic books, an EC line peaking, if that’s a right word, with content senate investigators would call deleterious to mental health of youngsters. Imposition of a “Comics Code” took ginger out of dime mags for a generation to come. Karloff’s own Tales of Mystery pulled its punch with the title alone, the stories thin milk beside wild-wooly EC efforts of not-so-distant yore. My interest was served in the 60’s by Creepy, a Warren publication where art was spun not in color as with comic books, for to do so on horrific terms would violate the Code, even late as 1964, so what we got was gore denuded of blood reds. Some of outlaw artists and writers from EC past again plied trade, Creepy and its sister success Eerie a newsstand presence I eventually got along without, for how many times could you tell essentially a same story?

Edmund Wilson in 1944 wrote a blanket review of the ghost anthologies. He could be severe upon books the rest of us call good, did not hesitate to pan even The Maltese Falcon for a column where he said mystery novels were largely the bunk. Maybe it’s no surprise that Wilson took a dim view of scare stories and said none could discomfit any reader over age ten, notion of ghosts having been product of a candlelit era “killed by the electric light.” As darkness was what bred spooks, all you need do to rout them is throw a switch and “flood every corner of the room.” Outdoors as site for haunting was undone by flashlights with which we could ferret out ghosts. Here was why such resolute product of a past century was best left behind as we entered a wired world. But how to account for recent slew of the supernatural? Wilson said it was “real horrors loose on the earth,” fantasy a means to cope with “periods of social confusion,” and come to terms with the madness of war via pleasure got from imaginary horror. The stories themselves “do not pretend to a literary standard,” said Wilson, most of them “trashily or weakly done.” He cited some authors who should have been included in the collections, but weren’t. Wilson having limited himself to elevated prose was not of mind to embrace “the phantom fringe which has been exploited by these anthologies,” even as he recognized that readers of such appetite would ignore his advice to seek more enlightened pastime.

The two Karloff collections were rivaled by Random House’s Great Tales of Terror and the Supernatural, which beat both for thickness and wider selection. Yet more was Dashiell Hammett introducing over 500 pages of “Chills and Thrills,” none having been published in book form previous. His was to-the-point entitled Creeps By Night, first appearing in 1931, back at half its original length in 1944 (so much for the 500 pages), a response to wartime demand for C's&T’s. So how chill/thrilling by today’s measure? The Hammett picks were of more recent origin, many having debuted in Weird Tales, which was why they were new to hardbound printing, Weird Tales down-market and regarded as anything but worthwhile literature. Future writers of note, however, began with pulps: Sinclair Lewis, Tennessee Williams, Louella Parsons (!), numerous others. Buyers could rely on 200,000 words in each issue, all pulps cut along same or similar pattern. Covers alone were enough to call out riot squads in response, lurid beyond what any Barnes and Noble would display in timid times we know. Never mind movies … pulps were where horror was most horrific. Did children do the buying, or sick-minded adults? Price varied from dimes to fifteen cents to two bits … depending on survival skills or cunning of your competitor. I could delve into and read the whole of pulpy lot, Horror Stories, Strange Tales, Dime Mystery Magazine, plus what was done with westerns, romance, war themes, but how to live long enough to fulfill such commission? I expect most fans read history of pulps rather than pulps themselves, few claiming merit in literature hurry-up generated at vast quantity. Adventure magazine during its peak came out three times a month, so how could minimum of 600,000 words, served every ten days, maintain any sort of standard?

I got through twenty or so stories from the two Karloff volumes and Great Tales of Terror and the Supernatural. But one needs to know when to quit, too many a route to numbness. Some are plain nauseating, others an escort to slumber’s portal. “Just four more pages and I can say I read it,” but say to who? Thing is, I like ghost stories, because, well, there’s always going to be a ghost, and I like ghosts, in fact believe firmly in them. I am further of opinion that most everyone has had some sort of supernatural experience but are loathe to admit it. The Random House book says in its intro that our fascination for such content arises from “fear of the human dead.” Think of sitting in a group of say four or six and telling them you once encountered a spirit. It would be all over town by tomorrow that you were nuts. A moment when I know I’ve won someone’s confidence is when they tell in sotto voice of having seen/heard something not of this earth. Consider advantage in a ghost, preferably someone you knew of course, popping by to explain what awaits on the other side. Poof would go mystery of life and death, let alone “fear of the human dead,” provided of course that no malign entity shows up to haunt sleep, meals, or leisure. Deep thoughts pulpy tales inspire! For the record, writers whose contribution I enjoyed: Somerset Maugham, W.W. Jacobs (how about that Monkey’s Paw?), Ambrose Bierce, E.A. Poe (who turns up in virtually all collections). Him what gave me most willies was H.P. Lovecraft, distinctly not someone I would have wanted to trade lives with, or accompany for barbecue, as here was a weirdest guy to have written weird tales.

Photos of Lovecraft, all of them, more than faintly disturb. Suffice to say, there are none of him basking at the shore with Carole Landis balanced on his shoulders. Lovecraft lived with Mom, theirs a “pathological love-hate relationship” --- sounds like the home life of 16mm collectors I knew. Then was an aunt, and another aunt, each with sufficient pathology to carry on Mom’s spirit-breakage of Lovecraft. A wife-in-brief was run off by the aunts. Mom had already died when he met the wife, not that she could have made things worse than they were. Lovecraft was said to have been second only to Voltaire for prolific letter-writing. One missive ran to 20,000 words. He spent a lifetime burying nuts for fame he would not live to enjoy, a talent far ahead of his time and most of readership. Lovecraft was prominent within a circle that understood him, these for sure no part of any mainstream. He was on the one hand anti-social, but helped young writers who sought his counsel. Lovecraft and readers who rubbed him wrong would feud for months in correspondence addressed to, and published by, Weird Tales. One of his sparring partners was a young Forrest Ackerman. Some said Lovecraft was good only for bottom-feeder pulps, but do please compare numbers with what was called serious literature. Weird Tales sold a half million or more copies per issue --- Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby moved but 25,000 units in the author’s lifetime. How soon we forgot that pulps had an enormous following. More people read them than most anything in print. Trouble is, few if any left behind thoughts or analysis, pulp the very definition of ephemeral. Like newsprint, pulps were not designed to last, so why would thinkers or critics pay heed to them? An Edmund Wilson did not address himself to stories like Satan Is My Lover or Cult of the Lusting Carcass. I doubt Lovecraft expected to be appreciated in his time, for who of genius was, or is, unless they discover some new digital realm?

Lovecraft had friends who came to his legacy’s rescue soon after he passed, two of them starting a firm called “Arkham House” to publish his works. Arkham was the fictional Massachusetts site of varied horrors Lovecraft invented, a cursed place we assume was based on Salem of the same state, where twenty so-called witches were hanged. Arkham may have been Lovecraft’s supreme creation. This place unlike Salem had real witches … goblins … fiends … among populace. Was Salem cursed for its prosecution of faux witches? Indeed, they might still be cursed, mutant children born in succeeding generations, or folks spontaneously combusting in streets perhaps. 1963’s The Haunted Palace, based on Lovecraft (The Case of Charles Dexter Ward) and set in Arkham, got dose of these. Famed author Nathaniel Hawthorne had a granddad who was one of the hanging judges, by name “Hathorne,” so shamed by posterity that Nathaniel chose “Hawthorne” to go by. Lovecraft’s cult was wide by the 60’s when first I heard of him. 1965's Die, Monster, Die derived from The Color Out of Space by Lovecraft, which I read and found harrowing, then watched the bled-white movie again to steady nerves. Lovecraft books Arkham House published now demand $4000 and up. Did Lovecraft see that much from totality of stories he sold to Weird Tales and spots elsewhere? Pulps overall have been ennobled by fans. There are oodles of books about them, inspired mostly by garish, grisly covers that could never have got through the door of Rhodes' Newsstand on my Main Street. What made pulps finally go away? There were over 200 of them in mid-Depression. Cheap Thrills by Ron Goulart (agreed to be a best history of pulps) put blame on the rise of comic books, Goulart saying these were “somewhat like buffered aspirin, (and) cut down the time it took for the action to get from the page to the brain --- and they took away much of the pulp’s audience.” Thing is, pulps still lasted, if limping, into the seventies. Ones who still care hold conventions. Video from these are at You Tube. Gatherings seem composed of boys that never grew up (not a knock, for who am I to talk?), with an occasional college professor to ruminate on the meaning of it all as he/she bargains for a Weird Tales or Horror Stories. I am fascinated by pulps, but thankful not to have been lured by siren call of collecting them. Do we still care as did those who knew pulps when they were current? Like with old-time radio, you wonder how much longer the party can last.

9 Comments:

Revisionist history is busy writing H. P. Lovecraft out of his place in the horror genre just as D. W. Griffith has been written out of his. That won't reduce the importance of either man one whit. It will make it harder for future generations to properly assess both.

In my early twenties I bought all the Arkham House H. P. Lovecraft collections. Read them all. Had nightmares, delicious nightmares, for months. One in particular I can still call up.I was pursued by a monster which I eluded by changing shape.

Forrst J Ackerman was the father of many of us. In the pages of FAMOUS MONSTERS we found a doorway into worlds most of us had never dreamed of.

Too bad the Ackermansion was not enshrined. It should have been. The place was a mecca for an imagi-nation.

The curse of being a pioneer in any medium is that over time, all your inventions and breakthroughs are imitated until they appear as obvious basics -- or when done badly, laughable cliches. A reader/listener/viewer determined to imagine what it was when new can't shake the memories of later workings of the same ground, and can never truly grasp that first impact. I'll own up to preferring the old B&W Universal horrors precisely because they've lost most of their power to scare. Were I one of the kids facing them for the first time, even a Mummy sequel would drive me under the seat or into the lobby. And you wouldn't get me back for the next one.

Griffith's revolutionary efforts shocked and challenged his original audience. Now, to generations raised on the film grammar built on his foundations, his films can only register as crude -- even when they're still emotionally powerful. Those who dismiss Lovecraft likely worship later writers who couldn't exist without him.

It's easy to be unimpressed by old pop culture. I make an effort to place myself back in time, to at least intellectually comprehend what it was for its intended audience. Lately, instead of binging on old cartoons I try to use them an appetizers to serials and Bs of the same vintage. I favor unfamiliar items like Woody Woodpecker, since oft-viewed Disney and Looney Tunes now irresistibly summon up memories of boomer television and hip college audiences.

My mother, born in 1921 in Plymouth, WI, told me that one of the movie theatres in Sheboygan offered $10 (in Depression dough) to anyone who would sit in the theatre along and watch a midnight screening of "Frankenstein." No one took them up on it.

In the cinema of my imagination, Karloff took off six weeks from the Broadway run of "Arsenic" (with Stroheim substituting, as he did in real life) to make the film at Warners with a borrowed Bob Hope and anyone (Curtiz? Bacon? Sherman?) but Capra directing.

"Hip college audiences..."

Oscar Hammerstein III said, "Being knowing and blase is really the sign of a very unsophisticated person. The most sophisticated thing one person can say to another is, "I know nothing about that. Please tell me.'"

College audiences tend to be the least sophisticated. To see the power of a great film watch it in a real cinema with a working class audience.

When it comes to silent films try to see them with real movie scores not the things that now pass themselves off as scores when we see these films on DVD and Blu-ray.

When an audience collectively moves forward in its seats during the climax we don't need anyone to tell us it is good.

Griffith's films when properly and powerfully scored have the power to move the audience forward in their seats. I witnessed that time and time again. But then I fine tune my scores for silent films by watching them work on my audiences. Sometimes all that is needed is an ambient background score.

$10 was big money then. Surprised no one took them up on it. The real horror of FRANKENSTEIN is not the physical appearance of the "monster" but seeing our self as the living brain in that re-animated body that thought itself dead only to come to a tormented consciousness in a patchwork body not its own.

Children understood that if their parents did not.

Karloff got tons of fan mail from children who identified with his "monster."

No other actor in that part has brought that out as clearly and effectively as Boris Karloff.

Christopher Lee did what he could but the writers gave him nothing to work with. In the Hammer films it is Dr. Frankenstein who is the monster.

The only scary movie experiences my father spoke of from his youth was the shot of Noel Coward floating dead in the ocean in "The Scoundrel", and the entirety of "Island of Lost Souls". Saw it only once upon original release, yet still recalled vividly Lugosi bellowing, "Are we not men?"

I always wondered about the extent of Karloff's involvement with the selection of stories in those anthologies. (There was a third one, published in the 1960s, which I still have somewhere in paperback.) It's somehow reassuring to know he really was choosing what he thought should go into those books. It was never a big secret that Alfred Hitchcock had little to do with that long line of mystery anthologies he "edited" for many years, beyond letting the folks at Dell use his name and likeness.

Couldn't resist checking to see. "Tales of Terror" is currently in print (with a rather lurid cover), as is "Great Tales of Terror and the Supernatural." "And the Darkness Falls" isn't. The great advantage of the new reprint is that, unlike the original, you can read it without fear that the book is going to crumble into dust faster than you can get through it.

You mentioned "Information Please." It's a favorite of mine, and a show of many surprises. It's probably the series around where you'll hear Jimmy Durante reciting Shakespeare, completely straight.

Pulp fiction was one of the "evils" that Miguel Cervantes was decrying in his great novel "Don Quixote" - in that book ( first published in 1615 - 400 years ago!) the protagonist Don Quixote was portrayed as having "absorbed the lessons" of the "novels of chivalry" which were tremendously popular amongst the "reading classes" in Spain in the 1500s, and Quixote's infatuation with those novels in turn formed the basis of his ridiculous "adventures" as described in Cervantes' novel, which follows the Don as he seeks to imitate and live the life which he had imagined was the proper way to actually live, his delusion arising as a direct result of his readings of those "pulpy" and now all-but-forgotten tales of knightly chivalry.

Personally, I suspect that reading pulp fiction generally serves as a better way for developing one's imagination than watching films, the latter seeming to be more of an an exercise in observation than imagination, since the film's images are presented to the viewer "ready-made" rather than being created by her "in her mind's eye" as is necessarily the case with written materials being read.

Dan Mercer comes up with one of Lovecraft's letters to describe the writer's singular eating habits (Part One):

Here is a passage I remembered reading, from a letter dated April 29, 1934 to Bernard Austin Dwyer on the stationary of the Charleston, S.C. YMCA:

A $1.75 per week eating programme is easy if you know how to manage it. It means merely keeping down to a quarter a day, and I can do that without half trying. When restaurants are high, I fall back on canned and package goods--knife, fork, spoon, and can opener being with me. A 5 cent package of ginger wafers is a more than sufficient breakfast, while a 10 cent can of spaghetti or beans will do for dinner--with the residue of the cookies for dessert. That's only 15 cents--leaving a margin for luxury on other days. Coffee can be cut out--it isn't much for nourishment anyhow--or at 5 cents a cup it isn't a great item at worst. In Charleston the cheap lunch rooms are so incredibly reasonable that I don't have to resort to "home cooking." I follow either one of two plans. Sometimes I get a dime's worth of ice-cream for breakfast, and a 10 cent bowl of Mexican chili con carne (with lots of crackers) and coffee for dinner. Total for the day, 25 cents. Or else I cut out breakfast altogether and stuff up at night on the incredible 25 cent bargain dinner provided at the Mexican Chili Place on Marion Sq. Boy, what a gorge for a quarter! It couldn't be approached in the north--Jake or no Jake! Not only is it a full feast, but a choice of three meats is offered. Last night I had the following Lucullan trough-feast....and all for one solitary quarter: pork sausage (generous allotment),fried potato, huge mountain of hominy, load of beets, two corn biscuits and butter, coffee, and bread pudding. Can you beat it? I fear it will set back on my reducing--although I've knocked off 4 lbs. since last Saturday, when I bade farewell to the dangerous luxury of the Long board. (By the way--my Y room is only $3.75 per week.)

Part Two from Dan Mercer (Lovecraft letter):

Lovecraft was on one of his trips, something he kept up until nearly the end of his life, but under increasingly straitened circumstances. When his parents and an uncle died years before, he came into a little money, but gradually used it all up. It wasn't through waste, but he simply produced little income himself. The reasons for this are many, but it essentially came down to his unwillingness to be a commercial writer. He thought that that was prostituting his talent. Most of the writing he did for pay was in the nature of ghost writing or revision work. He did write some stories, usually for the pulps and most often to Weird Tales, none of which paid much, but seemed determined to mishandle any possibility of supporting himself. Reading his letters, you'll see him turn down anthologizing his stories, having them gathered into a collection, expanding a novelette to book length, or having his editor at Weird Tales sell the radio rights to some of them, all to preserve the idealized image he had of himself as a gentleman writer. Most of his time was devoted to writing his many letters to a vast array of correspondents. When you read a letter a Hemingway wrote, it is abrupt and terse, with the barest amount of details, and no effort at all to make it entertaining. Those qualities he saved for the purchasing public.

His rhapsodizing about the Mexican Chili Place suggests how rarely he ate his fill any more. In that respect, he somewhat parallels my appreciation of Bell's Cafeteria when I was going to law school. As for his 25 cent a day "programme," that works out to $5.00 a day in today's money. It isn't much, and for that he largely subsisted on sugar and starch, with little in the way of vitamins, amino acids, minerals, protein, or fiber. While he may have gotten the bare minimum of calories he needed, he was otherwise starving. No doubt it lent the sense of despair one finds in so many of his stories. I don't know if eating like this led to the intestinal cancer that would kill him two years later, but it could well have disguised the symptoms.

Post a Comment

<< Home