How Meaningful Can One Movie Get To Be?

An Earth Stood Still Since '51, Then '62

Step forward please if The Day the Earth Stood Still resonates in your filmgoing life. “Going” for most was distance from chair to television, or consult with remote, as fewer each day know The Day the Earth Stood Still from theatrical experience. If they did, it would make them eighty or pushing that. Having known many who discovered Earth first upon its network premiere (March 3, 1962, on NBC), I’ve come to appreciate how meaningful that evening was for a generation now seventy years young or approaching it. These are folks who would not give one Day the Earth Stood Still for ten Star Wars, or any other sci-fi touched down since 1951. It is then, like all the rest, a generational thing, as in my childhood treasure is better than yours. I can be marginally more objective for yes, having seen The Day the Earth Stood Still on TV at age ten, but not having had life altered by it, being fonder of The Thing also seen first around a same time.

I wanted perspective broader than my own and so asked a collector friend of many decades what it was like seeing The Day the Earth Stood Still when it was new. Skip was at Day first runs, present for others of the burgeoning 50’s sci-fi cycle. He liked Day, but not so much as previously seen Rocketship XM, which boasted space travel Stood Still, with its “slow parts” and “no action,” lacked. Then there was Destination Moon, “boring,” Skip recalls, but for color, Man from Planet X registering as faintly, The Thing his favorite of the lot. So how did The Day the Earth Stood Still become fandom’s preferred of shared hindsight? Was it seeing Earth first and forever more on television, then of course, home video and now streaming? (lately on Amazon and Vudu in 4K). The Day the Earth Stood Still is a story with ideas, a thought provoker best contemplated in quiet setting, and more ideally, solitude. Earth was peacenik sci-fi cued to the sixties more than fifties from whence it came. A certain quiet pervades and that I suspect was what gave this one home-view status well above fly-saucers and bug-eye aliens tendered elsewhere.

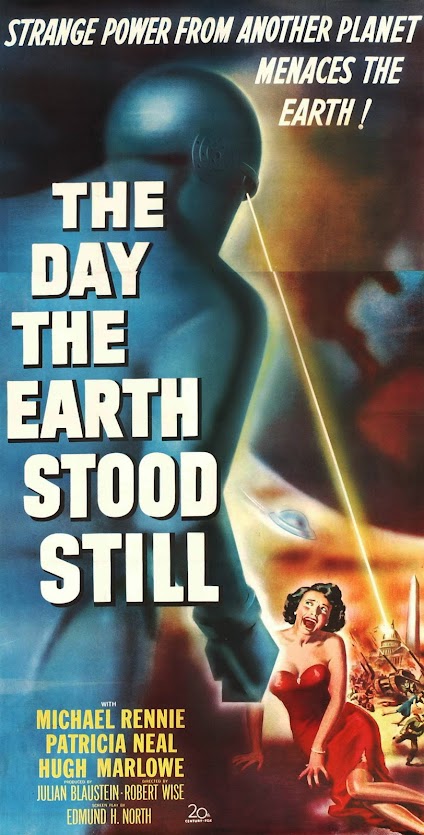

I found out how The Day the Earth Stood Still rated when my father came across a Channel 8 broadcast in 1965 and saw values he had not associated before with a thought-low genre. “If science-fiction is like this, I don’t mind your sitting up late to watch it.” Would this relax till-then parental stance toward my midnight habit? Testing what seemed new policy within the week, I announced intent to watch Channel 3’s “science-fiction” offer for Friday late night. What was the picture, they asked? THE GIANT GILA MONSTER, I chirpily replied, to which response was mute resignation, whatever good will came of The Day the Earth Stood Still mere puff of transient smoke. It seemed there was growing up to do before I would properly appreciate The Day the Earth Stood Still. Its message was plain, but was more Klaatu, less Gort, the deficit for child that was me? As with all 50’s sci-fi where robots figured, posters would foreground them. Gort was the principal for purpose of selling, a seeming contradiction to serious message The Day the Earth Stood Still tried to impart. The robot stands resolutely still for virtually all of run time, and it is Michael Rennie he picks up and carries, not Patricia Neal, her hair dark, not blonde (the half-sheet), her clothing intact always and never low-cut (the three-sheet). Had Earth’s promotion gone amok done product more harm than good?

Children were said to go about schoolyards reciting Klaatu, Barada, Nikto. Not where I attended. Perhaps in 1951 or immediate post 3/3/62. Seems love was either not had for The Day the Earth Stood Still or was intense. Few met it halfway. I knew a 16mm collector of many years whose first feature purchase was The Day the Earth Stood Still, $250 in hard-earned mid-seventies money. This was when Cinefantastique devoted much of Volume 4, Issue 4, to deep explore of The Day the Earth Stood Still, pioneering instance of one film historicized with no rock left unturned. Author Steve Rubin (since noted for his series of James Bond Encyclopedias) was able to track down and interview most all of Earth’s creative team, with remarkable result no one could achieve today, seventieth year having passed since The Day the Earth Stood Still was released and participants gone (apart from Billy Gray … is he all that remains?). Cinefantastique’s epic article is measure of what The Day the Earth Stood Still meant/means to constituents. Greater love hath fans for few else I can think of.

The Cinefantastique article in 1976 pre-dated Star Wars. Honors list of science-fiction was a shorter one: The Day the Earth Stood Still, War of theWorlds, Destination Moon, Forbidden Planet. 16mm projected prints of these were highlight of sci-fi gatherings where fans could see them on a hotel ballroom screen as opposed to shrunk TV. People who possessed such rarity stayed close to projectors unspooling their trove. Never mind how dupey or damaged 16mm was. They would do because they had to do, quite the contrast to what now can be viewed at home, not only The Day the Earth Stood Still in 4K, but War of the Worlds on souped-up UHD (as in Ultra-High-Definition). Yes, wires supporting saucers reveal themselves again in the latter, and 4K handed me a Stood Still surprise not noted before, enhanced clarity pulling back curtain on Times Square immobilized by Klaatu not in 1951, but 1938, theatre marquees advertising Love Finds Andy Hardy, with Marie Antoinette playing across the street. Was Klaatu able to accomplish time travel in addition to his other gifts?

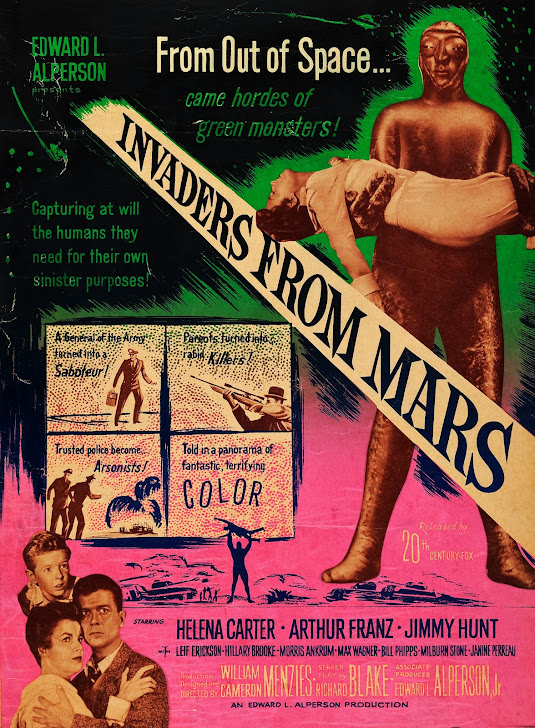

Very much alongside The Day the Earth Stood Still in fan estimation is Invaders from Mars, except it’s been for intent and purpose lost since new (1953). Independently produced, this was invasion but briefly conducted upon theatres, then gone but for odd bookings (our Liberty had a 1965 encore, a single “Late Show” one Saturday night), then black-and-white broadcasts to chill Cinecolor’s unique affect. A DVD to much later follow was but faint reflection of what Invaders from Mars once looked like. Closest I came to true encounter was Moon Mullins giving me a 35mm trailer with Cinecolor’s signature bright blue soundtrack. This was 1973, and I figured to never see the picture proper beyond this two-minute souvenir. Now comes restoration of found elements on Blu-Ray/4K for September release. Scott MacQueen of Doctor X and Wax Museum fame is involved, an assurance of quality result. What does Invaders from Mars mean to others of my generation? Everything it would seem, perhaps more even than The Day the Earth Stood Still, as all is told from a child’s viewpoint, Jimmy Hunt sole witness to alien touchdown and no one believing him, including parents claimed by body snatcher Martians. Lots saw Invaders from Mars on television and were traumatized by it, despite half portion that B/W amounted to. We’ll not recapture such first impressions however pristine discs end up. Going just part-way on a sentimental journey is yet value few would dispute, so expect this edition to sell brisk among the faithful, Invaders from Mars a perhaps last of sci-fi trophies to be reclaimed, if not acme of the entire lot.

14 Comments:

Born in 1948, I didn't see any of the 50's first wave of sci-fi in their original engagements. But with the help of reruns and TV showings, it didn't take that long for me to get caught up. Never liked "The Day the Earth Stood Still". Naivite of detail or execution in 50's sci-fi seldom bothered me. But it does in this one, I suppose because the whole film seemed to present itself as an artistic and intellectual step up for the genre. And I believe that's a reputation it still holds. So much of it seemed silly (i.e. the laughably sparse guards around the spacecraft) or dishwater dull. Bernard Herrmann's score is admirable - but deserves a better film to go with it. I like Michael Rennie and Patricia Neal but this script, I think, limited what they could do. And - yes _ I realize that Klaatu remains for most Rennie's claim to movie immortality.

Though I love 50's sci-fi I'm not a fan of some of the key titles in the accepted canon - certainly not of this or "The Thing". I've always wanted to enjoy "Invaders from Mars" more than I do And I admire its attempts at heightened atmosphere but a lot of them don't quite land for me. 'Forbidden Planet" has a great central concept but the whole thing's undone, in my opinion, by the sterility and phoniness of its look and the lack of delicacy in its central performances, not to mention that woeful comic relief and the clunkiness of Robby the Robot.

My favorite is and - I suppose - always will be "Rocketship X-M". A cast I loved playing characters I cared about, that lovely rocketship design, space travel, the long hauntingly tinted Martian sequence and a knockout ending that still resonates for me. Also love "The War of the Worlds" and the thrilling "This Island Earth". Even have a permanent soft spot for Monogram's "Flight to Mars" with its ever so cozy overlay of Cinecolored atmosphere.

But "The Day the Earth Stood Still" just doesn't do it for me. Much prefer "The Day the Earth Caught Fire" from Britain a decade later. Now there's a "Day" I find genuinely compelling.

That first still, in glorious color, was the cover of the book on SF films that Stu Stock and I published in 1982. Like the film itself, the book has been well received in the years since but didn't allow either of us to buy any of our dreams.

(Shh...I am a robot...)

I saw for the first time The Day the Earth Stood Still probably in 1993, on a late night broadcast on Brazilian television presented in its original language with Portuguese subtitles. Although at the time my English knowledge was not firm, the subtitles and their closeness to Spanish helped me to understand everything.

For me, this film and the other sci-fi flicks from those years feel bland, pretentious, and unengaging. The cast is good, but the story is quite silly and the posters and ads are the worst: they promote things, specially with the image of the terrifying blonde, that never appear on the screen. The acting is good, but the dialogs and situations are ridiculous. Yet, I prefer it to War of the World, which is one of the worst and frustrating films ever.

"Day" is on cable frequently, and I'll watch it every so often, and am always gratified at how well it holds up.

"Invaders," on the other hand ... well, it was a particular favorite of my sister and I when we were growing up, so we were thrilled when, about a decade ago, it screened at the Stanford in Palo Alto. We went to see it for the first time on the big screen, and came away thinking it was nothing but painted balloons. It's never been as good since.

Dave -- Read Glenn Erickson's piece(s) on INVADERS over at CineSavant. They will open your eyes to this child's nightmare of a film.

Ken -- Wow! Just wow...

@Beowulf: I have a lot of respect for Menzies ("Things to Come" is one of my all-time favorites), and I get the whole perspective of it portraying a kid's paranoia and psychology, but on that big screen, it looked cheap and cheesy and had none of the power it did when we watched it on television.

And this:

https://beatlememories.com/product/goodnight-vienna-album/

Think my first exposure was a college screening in the 70s, when I'd already absorbed some of its reputation as a serious message film.

Trying to remember the last time I went into a movie, big screen or small, totally blind (or informed by false advertising). Most likely from the days I'd go to double features at revival houses and UCSC festivals, drawn by one title and just sticking around for the other. Is it even possible to see a movie blind, without at least being exposed to a blurb?

Dave, Okay.... Point taken.

How meaningful? That must depend upon the individual viewer.

Dan Mercer tells of past encounters with THE DAY THE EARTH STOOD STILL:

I was one of those whose first acquaintance with “The Day the Earth Stood Still” was on its NBC telecast on “Saturday Night at the Movies.” I’ve seen it many times since then, perhaps most memorably on a summer evening when it was projected outdoors, the soundtrack with Bernard Herrmann’s score resonating off nearby Lake Hickory.

Having seen it so many times, though, I’ve become aware of plot developments which couldn’t have made very much sense even when it was first released. For example, would the U. S. government have allowed the flying saucer to have become, in effect, a carnival attraction, with crowds of people milling around it during the day and perhaps two or three guards at night, with no one else, not even the curious being present? This was the same government which had kept the Manhattan Project secret during the recently concluded Second World War, and which had troops scour the Roswell, New Mexico countryside for scraps and debris of a rumored crashed flying saucer, interrogating and intimidating residents who suggested that it was anything other than the weather balloon its spokesmen said it was. The government even then knew that important things and public scrutiny did not go together.

It also seems curious that Gort was able to leave the vicinity of the flying saucer and walk through downtown Washington, D.C. to the jail cell where Klaatu’s body was stored without detection or alarm, and to repeat the journey, carrying Klaatu’s body, remaining undetected. Similarly, the unfortunate guards Gort dispatched were apparently not missed nor was there any continuing scrutiny of the flying saucer during these excursions, even in this, the dawn of the television age.

No work of art is without flaws. What remains on those repeated viewings is a sense of wonder at the thought of vast intelligences watching us and taking the measure of our fractiousness, our disputes and conflicts, which suggest how evenly poised we seem to be between Heaven and Hell, whatever the level of the technology giving it expression.

The Washington, D.C. depicted seems of a different world from our own, one that is largely white, where people tend to interact directly rather than through instruments, and where they share many of the same values, the same strengths and weaknesses, but with an essential decency that seems muted today, if it exists at all.

For a god-like figure, Klaatu is a very human one, looking upon us with wry wisdom and even affection, but with an underlying ideology that will allow for the most ruthless resolution of a problem, if we prove to be such. It finds a response today, when much of our struggle is between those who will dominate and those who decline to be dominated. There is, unfortunately, little of the humanity of Klaatu among many of the participants, meaning that the common ground which ought to exist between men and women of good will is also lacking. Too often, the ideologically driven ruthlessness is not.

It is this probing thoughtfulness of the human condition that remains and fascinates, allowing plot flaws to be ignored and the passing of time to lend a certain poignance to the story it tells. I quite agree with your father. If science fiction is like this, then one shouldn’t mind a child of any age staying up late to watch it, or watching it at any other time.

John responds to Dan's comment:

I had forgotten about that occasion at Lake Hickory, an outdoor screening hosted by filmmaker Bill Olsen, the 16mm print of THE DAY THE EARTH STOOD STILL belonging to him. That would have been the summer of 1973. Do you recall we also brought along a chapter of FLASH GORDON CONQUERS THE UNIVERSE that I had recently gotten from Tom Dunnahoo of Thunderbird Films? Quality was surprisingly good for a 16mm dupe. The screening plus a cookout made for an enchanted evening overall.

THE DAY THE EARTH STOOD STILL was another one I had in 8mm. To say that TDTESS suffered when reduced to roughly 175 feet of silent super 8mm film is probably unnecessary.

I think it's helpful to look at "Earth Stood Still" in the context of 1951.

We're looking back on it with several decades of science-fiction - comic book, adult, psychedelic, kids - that have unspooled since then.

When "Earth Stood Still" was made, a science fiction film for adults was still new territory. In the previous months, pulp science fiction short stories had caught on with the public, published in magazines like "Galaxy". Mutual and NBC started series based on these stories in 1950 ("2000 Plus" and "Dimension X").

Before then, sci-fi was something that was for kids, like "Superman", or might be done as a one-shot oddball movie ("Things to Come").

"Earth Stood Still" basically plays like one of these pulp sci-fi stories, giving us a serious allegory for post-War uncertainty about the atom bomb in a sci-fi setting.

Many of these early pulp stories (and the radio shows they were adapted to) try to do the same thing. They tackle things like rampant consumerism, the influence and power of corporations or advertising, or the general feeling of existential dread of the period.

If you can look at it as one of those trying to be oh so serious pulp sci-fi short stories, then it works wonderfully for what it is.

Post a Comment

<< Home