Where Frames of Reference Splinter

Which Gets To Be The Highest Art?

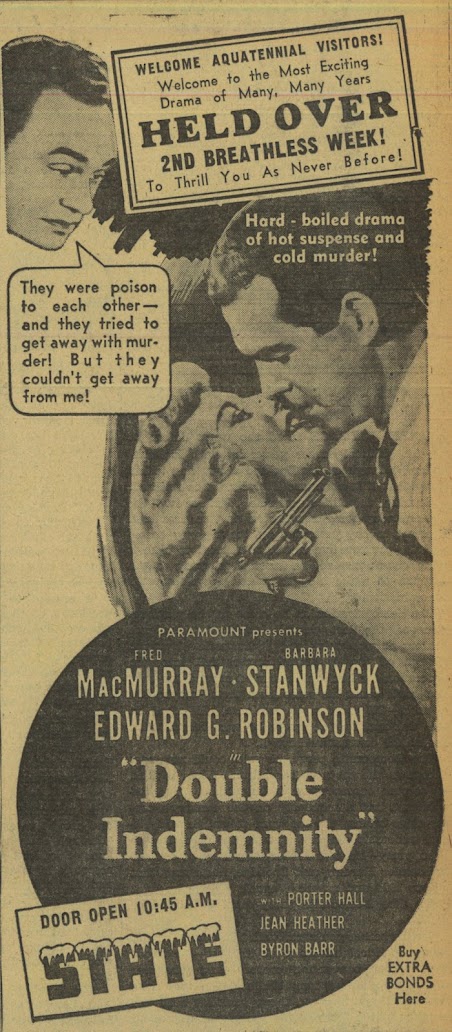

That 1975 summer out at USC had us part time in a History of Cinema class with instructor John Schultheiss, who knew his topic and shared greats from a Studio Era at a time when there was less to compete with a Studio Era. How have conditions changed since? Plenty, according to Jeffrey Sconce, who teaches at Northwestern University: “When film studies coalesced as an academic discipline in the 1970’s, it had about 70 years of film history to contend with … Now we’re at 120 or so years and the “classical” era is an even more remote sliver of total film history.” Remote sliver. But that's what hopeless antiquarians like me cling to. Take away my sliver and like S. Holmes, I retire to Sussex and keep bees. Whatever recognition, whatever context or frame of reference the older films had, is gone now. When Dr. Schultheiss showed Double Indemnity, a first time for me, there was comfort of known faces and names. Fred (My Three Sons) MacMurray, Barbara (The Big Valley) Stanwyck, and Edward G. Robinson (innumerable late shows) were anything but strangers. Each was recognizable going in and no adjustment need be made. Thirty-year-old Double Indemnity from 1944 was hospitable still for us watching in 1975, certainly so for this group of twenty-year-olds. The screening was like any gathering where one gravitates to those they know.

We turn on Netflix or Amazon Prime and scan headers for what’s familiar. Of “recent” titles, those of twenty years back or less, there are increasingly casts of strangers. So why take a chance with strangers? Then comes a Michael Douglas or Diane Keaton, still willing to work for amusement of us who no longer do, at light confections true, but these are what mature palettes stand best. There was one of late, D. Keaton as a long-ago cheerleader who transitions to an old folk’s home where she forms a senior pep squad. They enter a competition against mean teen girls … and win! My life was affirmed just watching, if sobered by Pam Grier as one of the seniors. Pam Grier. Could anything bring mortality so close, yet we watch because here are people we know from far back. Even their roles being diminished is a comfort. Billing which reads “… and Bruce Willis as Arch Stanton,” will occasion a look in, as does Jerry Seinfeld yet doing stand-up, even as his net worth climbs past nine hundred and fifty million. Bless their vitality, though Willis lately retired for reasons of health, three projects awaiting completion or release. How many players voluntarily walk away? Most stay, and are wanted, especially by those who stream and will pause for them. There was only one C. Aubrey Smith during the forties. Now there are a hundred of him. May Robsons too, if better preserved than was she. Meaningful names are at a premium, their number less likely to be replenished. Can stars be born at Netflix? Not rhetorical, but an honest question from someone who doesn’t pretend to understand the modern marketplace.

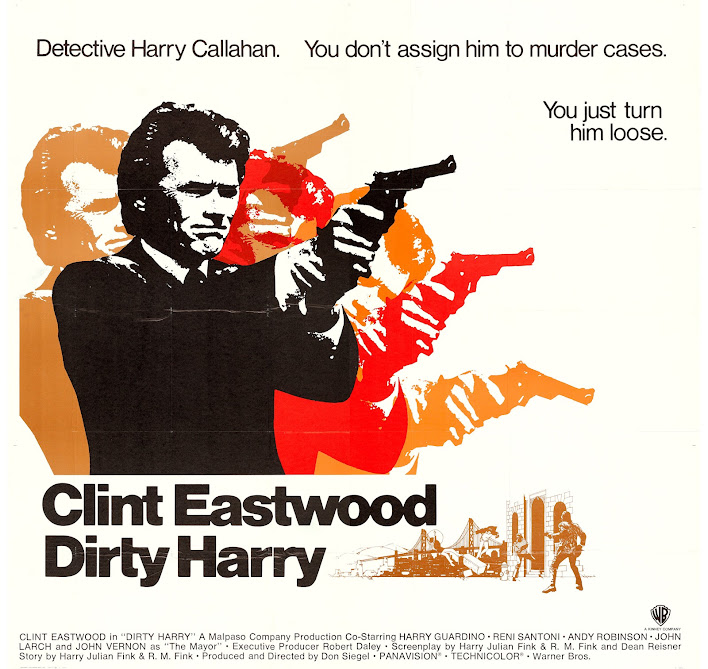

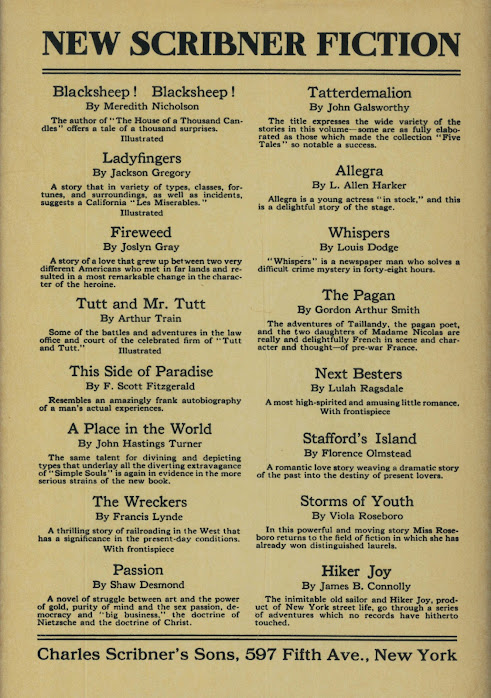

I had but to look back brief to see it all coming. When NBC premiered Dirty Harry in the mid-seventies, my father glanced up to a thing unfamiliar until Clint Eastwood entered. Well, there’s old Rowdy Yates … and from there he watched. That is me now. I need reassurance of the familiar to venture in, like dogs or cats who must sniff a thing before having a taste. Watching Double Indemnity recent was reminder that it, and a lot of us watching, belong more to that past than today. We know Walter and Phyliss and Keyes, and actors playing them, but how many born since say, 1980, will enter that cave? To paraphrase Neff at the Dictaphone … black-and-white, check … strange way they talk, check … everybody long dead and forgot, check … and what the hell kind of device is this guy talking into? Double Indemnity and kin represent more and more a ghost world. They are the eighteenth-century literature I was assigned to read in college. What entertained once will likelier oppress now, and not just with movies. Music long adored fades from playlists, faceless focus groups ordaining its end. Authors earlier read and enjoyed are listed en masse at Wikipedia as “largely forgotten.” Look for instance at the back cover of a first edition of This Side of Paradise, by F. Scott Fitzgerald. These titles represented “New Scribner Fiction” in 1920. Recognize a one, even one? I did not, yet all were popular that year. Go the next step … what movies might we recognize from 1920?

Plenty, as it turned out: Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (Barrymore), The Flapper (Olive Thomas), Last of the Mohicans (Tourneur, Clarence Brown), The Mark of Zorro (Fairbanks), The Penalty (Chaney), Pollyanna (Mary Pickford), Way Down East (Griffith), and Why Change Your Wife? (DeMille). A number of these are available on Blu-Ray. All can be readily seen somewhere. Of Scribner fiction listed for 1920, I’ll guess none remain in print, except This Side of Paradise. Said topic has lately been my tar baby, ongoing bafflement as to why so much, in fact seeming whole of literature from a past century, has gone by boards. “Unreadable” is the term I most often see, so tell me, are 1920 movies from the above list “unwatchable”? Stack up the eight, and given time, we might enjoy them all. The Penalty still wallops. I’m more and more of opinion that film is not only our liveliest art, but maybe a best surviving art. Has anyone surveyed past music or fine art to determine content that pleases still today? Here is part reason I say movies continue to abide: There were always stills for them … and posters … publicity material of every conceivable sort. Online assures such stuff will be everywhere and forever more. Frozen images of Chaney, Pickford, and Fairbanks are never more than a click away, not singly, but by thousands. You Tube is a resource for everyone that ever stood before a camera. I found a very arresting five-minute clip of Olive Thomas (Broadway, Arizona --- 1917) that someone lately uploaded, and the YT sidebar led me to a bio of the star with her life/death laid bare. Novels and their authors had little such advantage. We’re lucky to find a single photograph of ones who scribbled but never performed.

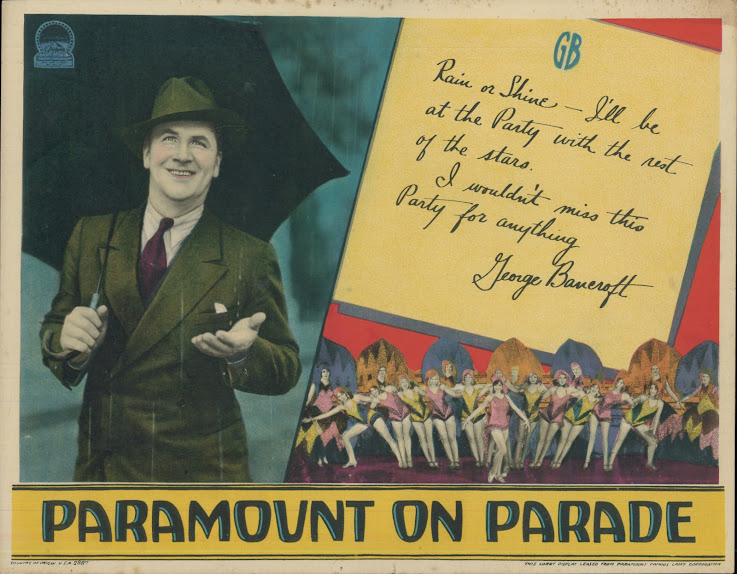

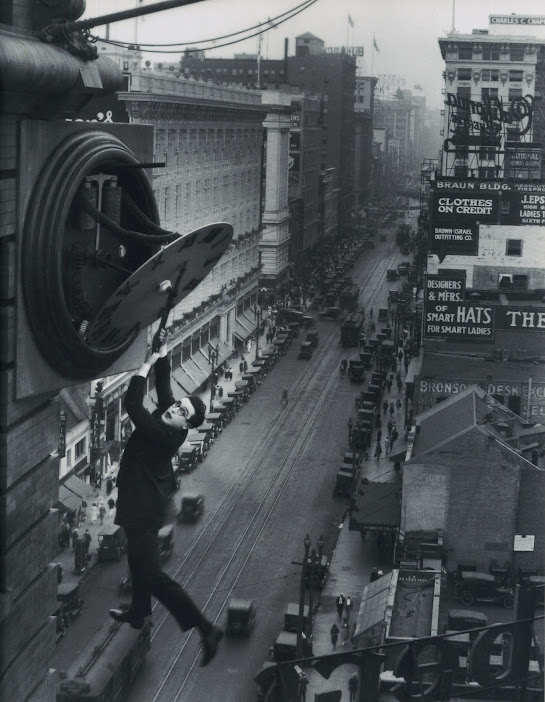

No one need be utterly forgot so long as there is Internet and fans memorializing them digitally. Olive Thomas is still someone’s sweetheart, as evidence ease of reference to her online, and my man George Bancroft sees renewed fame thanks to a half dozen of his features plus innumerable clip and tributes at YT. Above is my own salute, a lobby card of GB from Paramount on Parade which I’m sure will find its way onto sites and Facebooks, more kindling for a Bancroft fire still burning. Found also The Life and Death of George Bancroft (a 14:42 minute salute) which turns out to be someone else entirely, “an American historian and statesman” who lived in the nineteenth century. Greenbriar has uploaded a minimum of 25,000 images since 2005, and I cling to belief that inhabitants of Pluto may well discover George Bancroft and plentiful others from a GPS past. There was never such access to gone faces and films before the Net. Remember examining tiny print of an index that was A Pictorial History of the Silent Screen by Daniel Blum just to find one still from an obscure 20’s title? Today yields permanence for all, truest triumph of image over print. Little stands for literature except what of it was adapted for movies. I read an essay last night about Frank Norris, his work unfamiliar but for Greed and Moran of the Lady Letty, each known thanks not to Norris, but EvS and Rudy. I don’t believe Safety Last and Harold Lloyd will ever go away so long as that iconic photo of him hanging off the clock survives. Things seen lately at You Tube … a videographer wondering if the “Golden Age of Original Cinema” ended in the nineties. The nineties? Yes, that someone’s, many a someone’s, idea of a Golden Age. Point he makes is that this was pre-sequels, pre route without risk that modern industry habitually takes. Plaintiff exhibits as follow: Ed Wood, Pulp Fiction, Good Fellas, The Sixth Sense, Four Weddings and a Funeral. The list goes beyond good ones I named, but point is made. These all were what the speaker grew up with, knows best, clings to, ... and he'd be little more than forty now, if that.

Point is that those who were formed by films during the nineties naturally hew closest to them. They grieve loss of creative spirit that made the era possible. My generation is no longer alone for living in an exalted past. Much younger ones now taste the hemlock. But examine current evidence as supplied by streaming services, from whence much that is original springs. I looked at two last week, The Phantom Thread and The House of Gucci. Both engaged me, each bold in its way. Certainly not like what we’ve seen before. I wonder if those who complain loudest are simply not digging deep enough. Does anyone even know how many movies fill ether that is Amazon Prime, Apple, Netflix, so many others that stream? One You Tuber giddy on digital wealth proposed that “cinema” is the Greatest of All Art Forms, now or ever in the past. His comment column immediately saw correctives. No, it is video games that reach highest toward art, while others propose that virtual reality will wipe slates clean to embark us upon epochs not dreamt of before. I can believe that, but will I live long enough to see it? And who of us might be too timid to step upon moonscape of action narrative to do battle with flesh-eater zombies? How rewarding could such immersion be?

7 Comments:

Once again, inspired to further (albeit inferior) additions:

From the beginning, the movie business tried to sell brands instead of stars to avoid empowering actors. It's amusing to note that these days the big draws are synthetic: Superheroes, many of whom date back to the 30s (with newer ones carefully linked to the old reliables). James Bond, Harry Potter, assorted monsters. "Cinematic Universes" that sell not a specific star or character but ecosystems of overlapping stories. And, for at least one attempted "reboot", every old TV or movie property than can be owned. Down the line, will audiences remember characters rather than who played them?

A guess on why a lot of once-contemporary literature has a shorter shelf life is that readers were trusted to use their own lives to fill in the background. Good chunks of Benchley and Thurber are more puzzling than amusing to modern readers because their day-to-day tribulations are alien to us. Department stores, long-haul rail travel, bridge ... A passing reference a gaudy watch fob elegantly telegraphed a great deal about a character. Now you have to look up "watch fob".

A movie generally fills in the blanks simply by showing us what novels didn't (and once didn't need to) describe. When you see a flashy trinket dangling from a watch chain spanning a striped vest, surrounded by quieter conservative suits, you don't have to be a fashion historian to make inferences. Films that endure incidentally show us how the characters live and work, conveying enough to viewers even a century removed. Yes, you need to know about Prohibition to get why a hip flask means trouble for a college boy, and about rationing to get why a steak is such a big deal in a wartime movie. But most of the time context will carry the history illiterates.

Every generation believes their culture was better than what came after. During the early days of Saturday Night Live when Chevy Chase was the hottest name in TV, my mother would say. "You should have seen Jerry Lester on 'Broadway Open House'!"

Kevin K. is right about the conceit of every generation in preferring and valuing its own cultural products, or those cultural products of previous generations they in particular find most engaging; but what's different and novel for the present generation is our technology, which permits access to what once was only available by physically manipulating the books, tapes and films which recorded and reproduced works of literature, music, theater,and cinema, and which makes those works accessible at any time and in any place one could install the technology to pull in the signal from the airwaves, or more recently, the information from the internet.

There was a time once when there were no public libraries and literacy was far from being universal; just as there once was a time that in order for anybody to watch a movie, any movie whatsoever, one first had to either set up a film projector or go to a cinema. Not any more; now a display device with a network connection is all that is required to access antique, and even "up to the minute" contemporary, films.

Similar changes have been happening on the production side, too, and for a long time too: many more people now, compared to the people of previous centuries, can write; and our recent ( for forty years now) ability to access films of our own choice, in our own homes, without the need to fire up a film projector has now been matched by the ease with which films can be made - you no longer even have to purchase film to do so!

Those technological changes have had and will continue to have many effects on the ways in which we use and make these works of human artifice, which all "concretize" our fleeting experiences into forms which could easily outlast any single human lifetime so as to potentially entertain and/or enlighten members of future generations - should those future generations choose to look or listen to them, that is. There will always be contemporary artists producing new works to engage those who are simply not interested in any of the artworks of the past, and also to engage with the new, never-before-experienced aspects of human existence as they arise.

Science can illuminate this difference between the value accorded the physical object embodying the information and that accorded to the experience which engagement with the information embodied can generate.

See for example this recent research, which highlights how valued the mental experiences arising from engaging with those works can be, as compared to value accorded to the material embodiments - the actual physical books, drawings, films and recordings - which serve to preserve the information from which those experiences are derived:

Study: Individuals value information as they do material objects

"...In three studies—involving more than a thousand participants—the researchers demonstrated that people treat gains and losses of information as they do gains and losses of goods: as cherished possessions. They did so by showing that loss aversion (the tendency to feel worse about losses than to feel good about equivalent gains) and the endowment effect (the tendency to value objects we own more than identical objects we do not own) apply not only to money and tangible goods but also to information—even largely useless information (e.g., random trivia facts)...." Quoted from:

https://phys.org/news/2022-08-individuals-material.html

The Barrymore Jekyll And Hyde is genuinely creepy, terrifying and all the rest in ways none of the later versions come close to for me.

I saw that Jekyll and Hyde with an audience, and you could almost physically feel how creeped out everyone was.

My wife and I marvel at the older films' lack of teenagers in their casts. Movies in the '30s and 40's were aimed at the whole family and starred adults playing adults. There are actors over thirty and forty in films today but it they are stars they are playing way, way younger.

Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt, anyone?

When I started my film programs in Toronto in the late 1960s I was part of a generation around the world that wanted to see the films we had read about in film books like Paul Rotha's THE FILM TILL NOW and others. This led to the creation of campus film societies. When the people who had created those societies passed through their colleges and universities the presidents of the student councils appointed friends to run the film clubs. These people knew little about film. Most knew nothing. They programmed the latest hits. From this I learned that everything that is created by people who care is inherited by people who do not care. In Toronto student film programmers made small fortunes showing movies. After they passed through the system the next generation showed films for free so that no one could grow rich by "exploiting" the students. At Rochdale thee was one group that polled the residents to find out what films they most wanted to see. They ran those to capacity crowds to raise money for drugs. They did their best to keep me out. When I ran films like THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI (1919) they thought me crazy. Perhaps I am. It's the "crazy" people who do the great work. "Sane" people are boring. Ditto film studies. To get students new films are used as bait. Serious film study ended long ago.

Post a Comment

<< Home