The Jazz Age as Definitively Captured?

|

| Go Into Your Dance, Says Joan Crawford as Wild Child Diana |

Our Dancing Daughters (1928) is Fixed and Fantastic

Remember how awful Our Dancing Daughters always looked? A one surviving 35mm print was said to be master to each that followed, disaster a result of MGM in early preservation mode overlooking most rudimentary clean-up of a scratch-ridden surface. Even curlicue hairs were in for seeming keeps, frustrated viewers to wish a Tex Avery dog might step into the frame and pluck pesky threads like in Magical Maestro. I construct this wall of tears as lead to surprise that was TCM broadcast of Our Dancing Daughters this past week. They have finally done a fix, the how which I dare not venture, digital wand-waving that novices of us could not easy grasp. Enough that it is done and result is fresh life for a silent favorite we figured more-less lost. I use the word “silent” advisedly, as Our Dancing Daughters fits more my definition of a sound film than one doing without it. Here was MGM's first go at a fully synchronized music and effects score, so trades trumpeted. Big towns, that is key dates, got most gravy of that, having equipped early for talk surely to come. Our Dancing Daughters did everything but speak for latter quarter 1928 play, but hold, there are words by way of scattered exclamations and song lyrics. Our Dancing Daughters introduced an original tune, “I Loved You Then as I Love You Now,” cued generously throughout the feature and reflecting dramatic situation between star Joan Crawford and John Mack Brown. Let new levels of selling commence!, shouted Leo, for here came Metro entry, if tentative, into audible arena they knew was shape of everything to come. Denials, more wishful than truthful, issued even from Thalberg, who said silents would stay, but had to realize that no, they probably would not.

|

| Joan Crawford and Dorothy Sebastian. Image Courtesy Mark Vieira/Starlight Studio |

Intent of Our Dancing Daughters, any jazz age reflection, was to get as much flavor of the time as technology would permit. Silent depiction needed actor vitality to capture fads and language spoke by people we saw and heard, or just might see and hear, in life. High-octane like Clara Bow’s was compensation for fact she did not speak, at least before talkies brought her to dead stop and exposed vocal limitations (could hearing Bow, or anyone else, please everyone?). Spoken voice from flappers and sheiks could be spared so long as music and movement prevailed. Titles with their epigrammatic quality were passable voice substitute, for maybe we recall better quips seen printed on a screen. Our Dancing Daughters was a “silent” one could tap feet to. For all synchronization gave, there was loss of live accompany, at larger sites an orchestra to uplift visuals, the audience in receipt of something joyful to listen to if not look at. The term “silent movie” seems a misnomer anyhow, more so where hearing real instruments and singers was prime reason to attend cinemas, synchronizing music and effects more an economy move disguised as progress, theatres knowing they could save by ridding houses of pricey live musicians. Some complained, referring to “canned” accompany, audience interact to the pit and screen now an impersonal one. In fact, the pit was empty, room for more seats as management saw it. This came roughly under head of giving less and making us like it, or maybe fooling some of the people part of the time, or whatever it was Lincoln said. Fans were given wont only sometimes by an industry intent on having them think they got it all the time.

|

| Most Theatres Are Located in Dry Territory, Warned Harrison's Reports, So Why Inflame Patronage with Scenes Depicting "Drinking and Debauchery"? Image Courtesy Mark Vieira/ Starlight Studio |

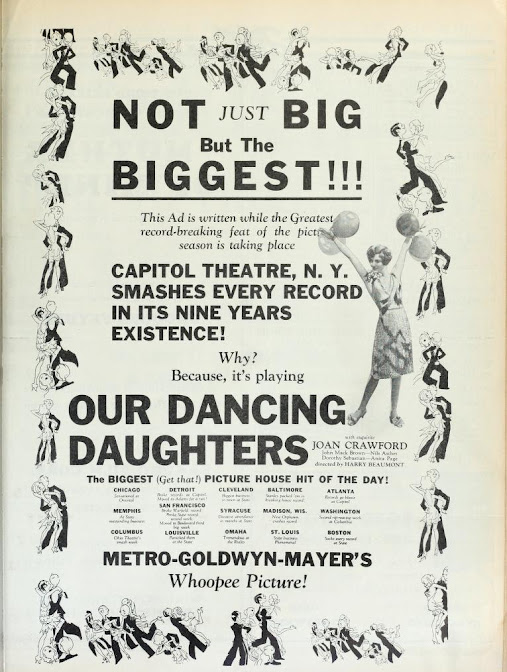

September 1928: The Capitol Theatre on Broadway makes trade event of installing sound equipment, patrons tingling with anticipation. Well, curiosity anyway. First with the frill would be Our Dancing Daughters plus selected shorts, audible all, at least with music/effects. Some would talk, a Van and Schenck reel and Fox Movietone News. Attendance records were predictably broken, pleasure especial in an Our Gang comedy, The Ol’ Grey Hoss, which benefited from gags spiced by sound. Noted before was that while big theatres took pains with a main attraction, live accompany customized for whole of their feature, fun stuff added was too often randomly scored, musicians not having been rehearsed for what seemed a less important extra. Hal Roach shorts MGM distributed got a boost for adding music/effects to some of 1928 output, these enhancing laugh quotient and crowd satisfaction. Our Dancing Daughters at the Capitol took a resounding $95,000 for its first week, more than half the film’s negative cost ($178K) got back in one frame at a single site. Synced shows did not come free, that is as part of price showmen paid for the featured subject. Records to accompany, cost of preparing same, was passed along to theatres already spent down installing sound equipment. Break-even became distant dream to houses weighted by gimcracks expected by patronage for dimes but paid for with dollars management could ill afford. Added attendance for the Capitol was thanks to no expense spared for publicity, and their address being Broadway. Such ideal setting and circumstance was not enjoyed elsewhere in the country. For many humble and far-flung sites, it was enough, had to be enough, just paying rent on Our Dancing Daughters and never mind sound discs that large venues enjoyed along with it.

|

| Deco Divine as Displayed in Our Dancing Daughters. Images Courtesy Mark Vieira/Starlight Studio |

Struggles from then to eat off Our Dancing Daughters are forgot now, maybe as well, for as with any art, it’s what we are left to look at that matters, and with uptick courtesy TCM, this now is considerable. Any epoch is less meaningful from hindsight: we want to have been there to feel impact of a jazz age, but be assured, Our Dancing Daughters as now constituted will put you near as any time capsule extant. This is twenties happening in the twenties, a party but short seasons away from being crushed by pitiless history. Recreation of roar times seem always suspect, not a little patronizing, as who among writers today or for a past thirty years could possibly have known it firsthand? I read how Joan Crawford was a real-life hot mama, won loving cups for dance skill. Did she look back on all this as quaint and let’s move on? Had we met on the set of Berserk, could I have inveigled Ms. Crawford into discussion of Our Dancing Daughters and cultural imprint it left? Everyone assumes actors had no insights, that they just acted. I’m not so sure of that. Anita Page was around to discuss Our Dancing Daughters and whatever else occurred to her over ninety-eight years living. She was seventeen when Our Dancing Daughters was made. Just look at the performance she gives and imagine what went through this comparative child’s mind at the time. People seldom reflect when history is happening to them, let alone give time to do so later when other concerns take precedence. This was besides a quick-live era not patient with back-touring. Wonder how many gone-to-ruin jazz babies indulged thought of freewheel twenties before jumping off skyscrapers in the thirties …

Our Dancing Daughters presents a mosaic of moral positions from which we may select examples to follow. One might ask if it speaks truth to today. More relevant would be to inquire if human nature has changed since 1928. Well of course it has, many might glibly answer, stance endorsed by crowd reaction to old film and pressure within ranks to agree. Remarkable how movies can be one thing with an audience, different entirely when you watch alone. How many seem quant because we are told they are quaint, dared in fact to think otherwise? (Essence of great melodrama: Laugh at it in public, cry with it in private) Our Dancing Daughters is of “three girls” formula where each embody choices wise or reckless, a set-up used late as the sixties. Bet ancient Greeks staged it in their amphitheaters. Moral certainty as expressed, as felt, was not solely product of a repressive “Code,” Our Dancing Daughters ’28 evidence to that, values here embraced without fear of recoil. Joan Crawford’s “Diana” is lively, a tease to extent, wily toward winning “Ben Blaine” (John Mack Brown), but honest enough not to seriously mislead him. “Beatrice” as essayed by Dorothy Sebastian has baggage (prior men) fiancée “Norman” (Nils Asther) accepts once she confides truth to him. “Ann” is Anita Page, spawn of a grasping mother who encourages her to marry Ben/Brown whatever devices needed to land him. Ben being heir to millions is incidental to Diana’s regard for him, but central to Ann’s pursuit. It is for the audience to sort out right/wrong, guided if not subtly by morality not nuanced. We may choose or not to comport like models here, take comfort in realizing others most certainly should. Viewers liked soothing mantra of Don’t Do as We Do, Do as We Say, hypocrisy of us all a shared secret between Hollywood and its public.

These Daughters are not teenagers, but young adults (notwithstanding Anita Page being but seventeen). They each are at marriage crossroad, the plunge taken advisedly or otherwise. Parents are disinterested, some predatory (Page’s mom steals her clothes and expects to live off whatever rich husband her girl gets). Central idea is to manipulate men into social obligation to marry, as simple a matter as spending too many night hours on a beach with an eligible member of their “set.” Our Dancing Daughters thus proposes marriage as entrapment practiced by cunning girls with sometimes help of family, a theme we’d not expect of three credited scribes Josephine Lovett, Marian Ainslee, and Ruth Cummings. Did these women understand facts of life we’ve forgot, or been told to forget? I don’t pretend attitudes such as here are irrelevant now, or best discarded because we’ve progressed so far. That trivializes reality as it was accepted at a time and among a class that exists still, Our Dancing Daughters dramatic-licensed sure, but aware it must connect in meaningful ways with those expected to identify with men and women as each appraised the other in 1928. Our Dancing Daughters may (in error) be dismissed as trivia, but I’d not dismiss it by assuming all that happens could not happen in life, then or today. Films did not emerge so profitable as this by telling lies.

Greenbriar Archive stops in on Dorothy Sebastian (1/1/2006) and Anita Page (6/18/2006). Also Daughters follow-up Our Modern Maidens (1/1/2008).

3 Comments:

Many years ago saw a stage revue of Cole Porter songs, with his life sketched in between numbers. The following season the same group produced a Woody Guthrie revue, likewise sketching in his life and times. It was only afterwards I abruptly grasped that Porter and Guthrie co-existed for many years, living and working in two very different Americas. Just a thought.

Anyway, the high life displayed in "Our Dancing Daughters" invites a closer look. Was Anita Page's golddigger, coached and pushed by an avaricious mother, really an anomaly? Or were many or even most of the dancing daughters similarly climbers, using their looks to get into posh parties where they might snag a young heir or perhaps his old father? For that matter, how many of the boys were pretenders, upward-striving college chums and other hangers-on looking for fun or connections?

In real life, one suspects the aspirational moths were more often burnt than brides, a canny/lucky few leaving with a bankroll. A little like short-burning Hollywood stars, but without film credits for their obituaries.

In Dumas's D'Artagnan books, French aristocrats would each have their little entourages, who in turn had their own entourages, with jockeying for position at every level and favors filtering down from patron's patrons. In our own time we see sex, money, and fame openly traded, those with access to one or two transparently bargaining for the third. What modern scandal is complete without numerous players of vague and doubtful employment? Political and business figures of outdated or nonexistent achievement often identify as consultants, a fig leaf when marketing themselves as experts on news shows and sometimes useful for monetizing friendships with actual executives. At the bottom of the scale are influencers, self-proclaimed celebrities who no longer need any entertainment credits.

I describe myself as an author because of one self-published title several years ago, but that's entirely different.

Further babbling:

With very little rewriting, Anita Page's character becomes Cinderella. Mary Pickford, Clara Bow and Colleen Moore were just some of the 20s stars playing lowborn heroines who landed American princes, often with mean-spirited rich girls as rivals. Was "Our Dancing Daughters" an outlier in presenting the lower-class contender so negatively?

Where official heroines are rewarded for being more virginal than their rivals, Page is a villain for consciously deploying it against Crawford's perceived sins. Moore in "Why Be Good" ultimately wins her man by asserting her virtue, but it's not a stratagem -- she's genuinely furious when he "tests" her at a roadhouse. Bow in "It" rejects an offer of being kept, but even in the context of the film you wonder if she's being virtuous or sensible. The difference seems to be that Moore and Bow are not explicitly expecting virtue to pay off -- even though it usually does in movies -- while Page is frankly monetizing it.

At the end of "My Best Girl", Pickford pretends to be bad to drive away the hero for his own good and that of her family. Of course love and good reputation eventually triumph, but only after she proved noble enough to sacrifice them.

Perhaps this is why "Her Dancing Daughters" takes time to make Page and her mother Bad People: they scheme, they quarrel, they're greedy. Their lives are dedicated to baiting a rich man into marriage. Do they have ANY redeeming or sympathetic qualities, beyond Page registering as a bit pitiful in her last scene?

In contrast, the other films work to scrub off most hints of romantic calculation. Moore is a hardworking shopgirl -- a superior mentions that she's very good at her job -- living with beloved working-class parents. She meets the hero and seems set on him before learning he's rich; that development is icing on an existing cake. Bow shares humble digs with a single mother and child. One suspects Bow pays most of the bills. She risks her reputation fighting on their behalf. That mitigates some of the calculation in her pursuit of her boss. And Pickford in "My Best Girl" is of course noble and self-sacrificing as well as virtuous, willing to give up the hero for his own good and for her family.

Oscar Wilde had a line to the effect that women don't marry for money; they make sure to fall in love first.

Wonderful post! It occurs that Crawford herself used her beauty, sex appeal, and dancing skills to go clubbing (and winning cups) just to be seen by all the “right people” to further her career — successfully. And she did end up crashing (and marrying into) “society.” “Society” being the Fairbanks and Pickfair, but that amounted to aristocracy in Hollywood at that time.

And thanks for posting about the restoration. I have attempted to watch ODD more than once, but was defeated by the poor quality — looking forward to the restoration currently sitting on my DVR.

Post a Comment

<< Home