Gatsby to the Screen, Then Disappears from It

Greatest of All Novels Inspires Best of All Movies?

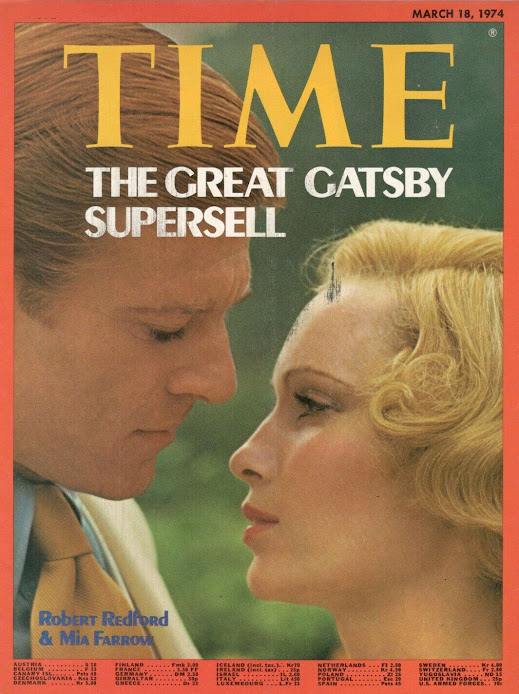

1974 was the year I just had to have a Gatsby suit. They were white, had a double-breasted vest, and were inspired by the Paramount motion picture starring Robert Redford and Mia Farrow. Trouble was the outfit not looking on me the way it had on Redford, being off a rack and anything but a tailored fit. Away went this Cinderfella to our fraternity banquet even if ensemble was chilled by a wide tie more 70’s bleak than 20’s roar. Such was fashion compromise for one who wanted really to live in the past, not just make faint gesture toward it. I cared less about the movie than the look, which was everywhere in magazines, even TIME which did a cover feature. The Great Gatsby turning up at our College Park was superfluous. I didn’t even stay to watch it end. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel by 1974 was canon-certified plus the biggest seller of as-old books. That had been case for a long time but did not begin so in April 1925 when published via Scribner’s. Fitzgerald went a different direction here, his first two novels straightforward dissection of vibrant age he and a country were living in, plus there were short stories of flappers and a jazz age told from inside that was the author’s own experience. But Fitzgerald knew Bernice bobbing her hair could not sustain. Trouble was he and wife Zelda by 1925 drunk on success and spirits that enabled, living in hotels, specifically at French Riviera address beyond means of advance money from guiding editor Maxwell Perkins at Scribner’s, who with Fitzgerald expected The Great Gatsby to surpass previous This Side of Paradise and The Beautiful and Damned in sales. Fact this didn’t happen was ruinous to Fitzgerald’s morale. 23,870 copies would have suited most authors of the time, not those with Scott’s expectation.

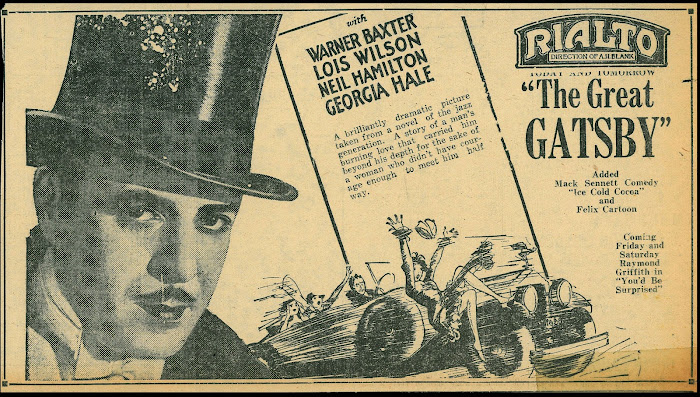

The Great Gatsby was right away adapted to Broadway, veteran of stage melodramas Owen Davis credited for “A New Drama … from the Novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald.” Paramount did a screen version, released 1926, and starring Warner Baxter as Jay Gatsby, with Lois Wilson, Neil Hamilton, Georgia Hale, and William Powell. We can only see a theatrical trailer today. The rest is lost. Glimpse at hand shows a Gatsby party more authentic than ones depicted for later movies based on the story. Maybe that’s because this Great Gatsby was produced during the era when Fitzgerald’s drama took place. Remakes would be speculation as to what life was like in the mid-twenties, effort strained too plain. The silent Gatsby was alone for not having to recreate a story that happened in the film’s then-and-now. What a valuable find this version would be. Fitzgerald pushed for reprints of the novel, hoping a later and more sophisticated readership would appreciate The Great Gatsby better, but efforts during the thirties came to little, possibly because content dated and a Depression public found Gatsby a harder character to identify with. Other books anyway sold better, Anthony Adverse for instance at over a million copies, never mind its being forgotten now. The Great Gatsby was so gone by the late thirties that Fitzgerald could not even locate a copy in Los Angeles when he wanted to buy one for companion Sheilah Graham. Maxwell Perkins still put The Great Gatsby among best novels he ever represented. There were authors who sold better, but for Scribner’s, a prestige name meant much, and Fitzgerald would never be less than such a personage. Even where a Marcia Davenport wrote The Valley of Decision and Scribner’s sold 300,000 copies, Fitzgerald’s standing went undiminished.

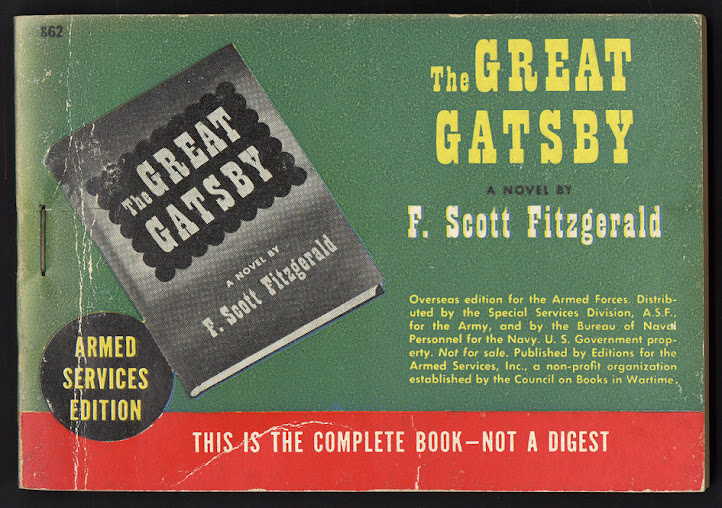

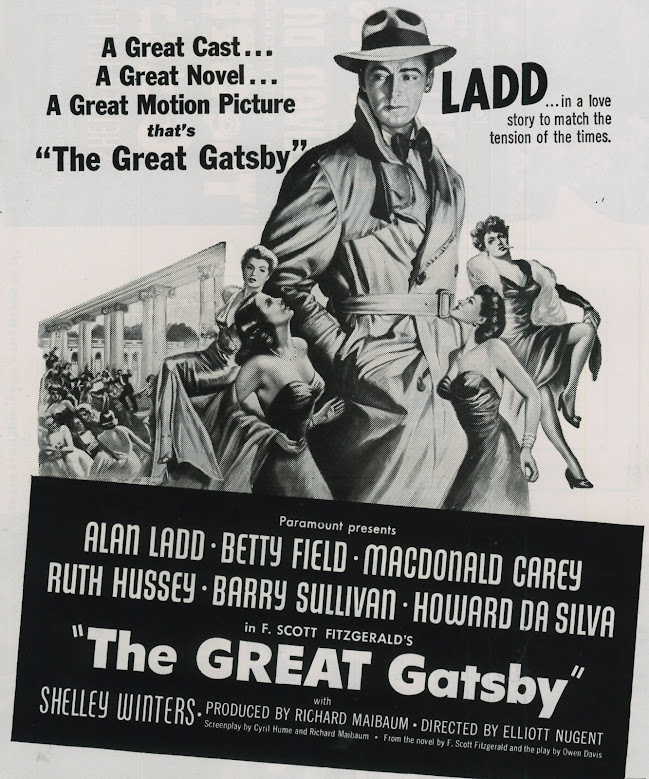

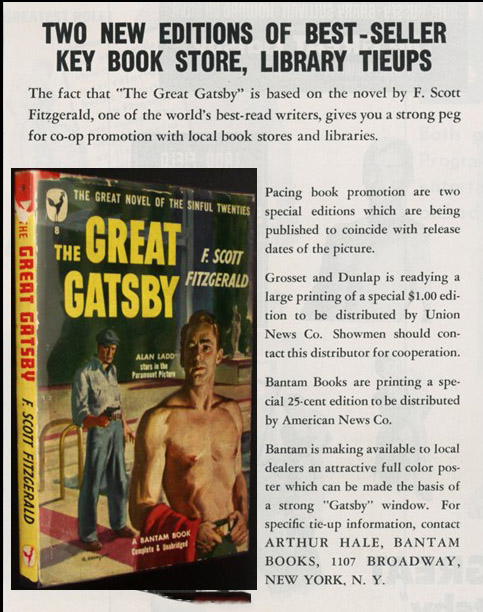

A publisher could break even, lose money, on a worthy enough name for whom any effort was justified. This was not unlike Hollywood sponsoring a Sunrise or The Crowd to challenge plebian status, or worse, image as defined by literary lions like John Dos Passos who referred to film studios as “public brothels.” But publishers kept cathouses as well, those least burdened with talent often ones that sold best. Check a 1933 precode called When Ladies Meet, where Myrna Loy is the hack authoress tended by publisher Frank Morgan, who knows her novels for cash cows they are, and is not too proud to sponsor whatever she chooses to write, so long as sales are brisk, which certainly they were for “damn scribblers,” a term Nathaniel Hawthorne tabbed for writers popular with their public, but devoid of literary talent. The Great Gatsby began a comeback several years after Fitzgerald’s 1940 death when the Armed Services selected it for distribution worldwide to US combatants, exposure that undoubtedly widened The Great Gatsby’s home front readership as well. Was positive word-of-mouth in V-mail a spur to stateside reprintings and sales? Paramount by 1949 wanted to remake The Great Gatsby, now stuff of nostalgia for bathtub gin, the Lindy Hop among amusing excess of the twenties. Fitzgerald’s novel was still this side of venerated status. He had said that someday it would become the preserve of “schoolmasters,” but perhaps fortunately, that time was not yet. The Great Gatsby would be a vehicle for Alan Ladd, ideal casting given look and melancholy Ladd brought to all he did, plus here was a part the actor identified with, being of humble origin like Gatsby and having moved comet-like toward stardom that seemed unlikely most of all to him.

Self-doubt had been fruit of Gatsby from a first week in 1925 when tepid reviews plus selling limp at start had Fitzgerald second guessing everything from the book’s title (he was never happy with “The Great Gatsby”) to fact, or so he believed, that the story lacked compelling female figures. Fitzgerald like many authors was better with character and descriptive prose than bedrock narrative that of course movies had to depend upon to keep audiences seated. Story must come first, as playmaking Owen Davis knew, as Paramount realized in 1926 when first they dealt with the property. Great novels were toughest for obliging Hollywood scribes laboring twice as hard for licks they'd take from critics excoriating them for yet more Hollywood rape of art. Blades were sharp from announcing The Great Gatsby for another adapt. Trouble with 1949's was/is disappearance after general release. There was no television packaging thanks to Paramount’s limited license in the literary source. They owned the negative but could not exhibit it. A few, very few, prints floated in 16mm. I had one that was trimmed of kissing scenes, I mean the moment when lips touched, which made watching an odd experience. A Region Two DVD is around, OK for allowance we make for having the movie at all. A lot of writers judge The Great Gatsby on basis that no occasion for Alan Ladd playing this (or any?) part should be taken serious. I plead different, but never mind him for the moment and consider capable others in support: MacDonald Carey, Betty Field, Barry Sullivan, this Gatsby easily a most polished in terms of cast and production. What might Universal have to spend to clear The Great Gatsby for streaming or disc release? More than they’d be willing to, I suspect.

Could any actor be unanimously accepted as Gatsby? The character registers strongly in print, but as with anyone we meet on literary ground, the impression is subjective, oft-time personal to a point where no interpreter will do. For critics steeped enough in literature as film’s forever superior, which most were lest they lose face with other critics, prospect of Alan Ladd for Gatsby was a thing to be derided. What they failed to realize, or refused to acknowledge, was Ladd being more a cultural icon in 1949 than Jay Gatsby could approach, and it was for The Great Gatsby to conform itself to expectation of the star’s audience of the time, not preference book readers might harbor or express. This alone separates the ’49 Gatsby from versions done before or after, as Warner Baxter of the 1926 silent was there in service to Fitzgerald’s conception, at least we assume that was the case but cannot be certain so long as silent Gatsby continues to go missing. Robert Redford’s 1974 screen persona was nowhere near so defined as Alan Ladd’s in 1949. Rather than seeing latter as a weakness, I regard Ladd gravitas an asset to plenty else he brought the Gatsby character and am not alone for declaring his to be a most satisfying screen interpretation to date, though I’ll cop to not seeing Leonardo Di Caprio’s interpretation in a more recent Gatsby (2013), however intrigued that a 3-D version was tendered and is available on Blu-Ray.

There is a book called Forties Film Talk by Doug McClelland, based on his many interviews with surviving talent from a decade left far enough behind for participants to speak plainly of it. Published by McFarland, this is a splendid record of Hollywood and people who toiled there. Several sections address The Great Gatsby, thanks to conversations McClelland had with Barry Sullivan, Ruth Hussey, and writer Richard Maibaum. Latter was who suggested The Great Gatsby for Alan Ladd after being taken by the actor to see his personal wardrobe closet that stretched from one end of a room to the other, just like a scene in Fitzgerald’s novel. Maibaum satisfied Ladd that he was Gatsby and got a fully committed performance from him, Ladd talking hours of the character as he pondered nuance to add. Gatsby’s mystery past was in fact Ladd’s present for fitting neatly with the star’s screen identity. It was faithful then to show Gatsby shooting it out with rival bootleggers or slugging a gangland confederate who has crashed his Long Island party. Barry Sullivan said these scenes were added after principal photography to assure Ladd fans getting what they would expect, but again, it works and lends strength to what may otherwise have been too passive a part. Ruth Hussey quoted Ladd’s philosophy as expressed by him to her: “As far as I’m concerned, all acting is in the expression of the eyes.” Would this not be a best approach for any player who sought to register on film? Sullivan said Ladd noted the beginner’s inexperience ("I was doing things too big for the intimacy of the camera") and arranged to screen rushes with Sullivan in order to point out technique that would register better, “and he’d be right. I was much more comfortable in films after that.” Still, it was for Paramount to “protect” Ladd, so that in final analysis, any character he essayed would be cut to his measure rather than that of any literary antecedent.

I read and hear discussion of The Great Gatsby as the Greatest of Great American Novels and wonder if this derives from joy of reading it, or pride for getting through it. Lots of classical literature represents a climb, “not an easy read” as so often put. Does The Great Gatsby sustain for being short? (208 pages and done in three hours provided one does not linger) Several mention how they took years to develop true fondness for the book. The Great Gatsby must be complex, as in each visit yielding fresh revelation, stamp of any literature most admired, else why the rank? I would ask Gatsby authorities how many fell in love with the novel from a first discovered page. Is this, like most great books, one that must be grown into? Embrace of a favorite film for most comes immediate, though there are ones to cook slower. More books are out there about Fitzgerald than for anyone who ever wrote or directed a movie. A woman lecturing at You Tube startled me for saying that apart from The Great Gatsby, Fitz’s outstanding work really was just some short stories and certain of letters he wrote. This Side of Paradise and The Beautiful and Damned, his first and second novels, amounted to beginner efforts, and Tender is the Night, his last to be completed, was flawed (her assessment, not mine). So, all this study, decades of research and teaching, for a writer who was truly great but once? Take away The Great Gatsby and he’d be Elinor Glyn, or maybe the nom de plume who wrote Flaming Youth. If I knew literary scholars better, I would ask one of them about this. Everything of course comes down to comparison with films. What writer or director do we celebrate for having made but one masterpiece? Not that all of academics would agree about Fitzgerald, and I’m no authority to claim one way or the other. Let’s just say it would be tough lauding Ford, Hawks, or Hitchcock if there was so little of permanence between them. Thing is, the literary community would argue that none of what we celebrate is worthy of even weakest work a Fitzgerald did, but is that really because movies still aren’t accepted as art, let alone on a parity with written words? If so, the issue turns again to film as collaborative, which for many means can’t be much good, or ongoing shame that people eat popcorn while watching. Anyway, I’ve decided what my next book should be … the life saga of Edward L. Cahn, who in 1932 directed Law and Order, if nothing else distinguished before or after. But wait, what about It! The Terror from Beyond Space? I think I'm on to something here.

22 Comments:

I exhibited the Redford GATSBY when new. Paramount promised us full houses. Mandatory three week booking in my smaller town.

Crickets.

Forced Paramount to get it out of the building after two weeks.

Gee...we even provided daisies to pass out to the ladies when they entered our lobby.

Threw out a bunch of dead flowers.

Am a bit surprised you haven't caught the Baz Luhrmann version yet. Also surprised you didn't mention that frequent Ladd co-star Howard Da Silva pops up in both the '49 and '74 films (Wilson in the first, Meyer Wolfsheim in the other)

I have the 3-D disc of the modern remake, but haven't gotten around to watching.

Didn't want to incorporate it into this column, as it would have gone on too long if I had.

I love the 3D GATSBY.

I tried to watch the Leonardo Di Caprio remake on a long night flight and I found it boring and too opulent and exaggerated that put me to sleep.

For the silent film I have rescued a nice ad illustrated in Brazil featuring an image of Warner Baxter.

I could get, also from Brazil, the synopsis of the lost silent version: they are very faithful and when I got the one for THE AMERICAN VENUS I was able to watch the trailer again and place all the images in their original context.

I recall approaching each of the sound versions of "Gatsby" with fairly high hopes. And emerging somewhat disappointed from all three.

For me, the 40's take just kind of plodded along. And never seemed able to take advantage of Ladd's unquestioned rightness for the role. I'll bet another director might have been able to do more with it. William Wyler, maybe or George Stevens, who was to capture Ladd's personal aura so well in "Shane".

I'm an admirer of Betty Field, a fine fine actress. But just not a good fit for Daisy. I actually think she'd have been better off playing Shelley Winters' wrong side of the tracks character. That said, though, Winters probably gave the picture's most effective performance - though it wasn't even prime Winters. I've always figured Gene Tierney would've made the perfect Daisy in the 40's. Certainly her Isabel in Fox's "The Razor's Edge" was close in type and she carried that off magnificently.

The '74 "Gatsby" was better, I thought, though nor great. Opulent for sure - and the wonderful Irving Berlin song "What'll I Do?" was used to poignant effect. Redford was okay and Mia Farrow made a better Daisy than Field. Seemed much more at home in the ritzy milieu. Sam Waterston and Lois Chiles both brought the project up a notch with impressive supporting work.

Baz Luhrmann's "Gatsby" was sunk for me by its use of modern pop music for the soundtrack. May have made it connect more for youngsters but not for this old fogey. Also DiCaprio seemed a bit over his head in the title role. Though I recall that Tobey Maguire made a great impression in the same part Waterston had aced in the 70's. Carey Mulligan, I'd say, was the best screen Daisy Hollywood's come up with so far. Really enjoyed her take on the character. But then - for me - this is an actress that can do no wrong.

Gatsby became a Snoopy fantasy in 1998:

https://peanuts.fandom.com/wiki/Scott_Fitzgerald_Hero

There were also earlier strips where a smaller, Gatsby-obsessed kid had a crush on Charlie Brown's sister Sally:

https://www.gocomics.com/peanuts/1991/06/07

I've yet to attack the book or any adaptation, but I do remember the ballyhoo for the Redford-Farrow movie and the fallout from its failure. Part of the buildup was a tie-in with white Teflon cookware. The producer was David Merrick, fabled/notorious Broadway impresario whose bombs were as epic as his hits.

Richard Maibaum wrote an amusing article about the Great Gatsby for the LA Times (July 15, 1973). The original director was John Farrow, but he fell out with Maibaum over who should be Daisy (Farrow wanted Gene Tierney). Ironically the next Daisy was Farrow's daughter.

Maibaum knew Ladd was the perfect Gatsby after "Alan took me into his bedroom, to show me his wardrobe. He must have had about 60 shirts and seemed pleased when I looked duly impressed. 'Not bad for an Okie kid,' he laughed. 'Eddie Schmidt makes most of them for me.' Like an echo in my mind I heard Jay Gatsby say, 'I’ve got a man in England who buys me clothes…’"

The Breen office found Gatsby’s script totally unacceptable. Maibaum felt “Fitzgerald was anathema to Breen and the Legion of Decency. They had banned his screenplay, 'Infidelity,' and the subject matter of his novels in general represented everything they opposed as screen entertainment. Furthermore, Fitzgerald had antagonized many producers in Hollywood…by his obvious contempt for it. We found an accumulated resentment toward him and his writings which went far beyond the usual operation of the code.”

Maibaum argued that Gatsby “was actually a morality play depicting the dire results of irresponsibility" and a version of the Faust story. He felt there was “only slight justification for this interpretation” but was “desperate to get the film made.”

“Make that clear to the audience,” replied Breen. “Cut out the explicit code violations, just infer all that jazz, clean up the characters a little, and we’ll see what we can do for you.” He then suggested a prolog. So the film started on Gatsby's tombstone and its biblical quotation.

[Continuing from my previous comment]

In retrospect Maibaum felt this “was anti-Fitzgerald, too explicit, too much on the nose. Fitzgerald wasn’t a moralizer. When you dumbed things down like that you lost his elusive quality. The beauty of his writing was always somewhere on the periphery of his narrative, never near dead center…

"Perhaps I shouldn’t have made the film with the limitations he imposed. Ten years later a similar situation occurred when Cubby Broccoli sent me several of Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels to read. We decided against them at the time because the code was still operative and we felt that cutting out the sex and violence would damage 007 irreparably.” They waited several years and found success. “In that regard I’m afraid I served Fleming better than I did Fitzgerald. Incidentally, I only met Fitzgerald once and Fleming several times. I respected them as authors but didn’t care for them much as people. I thought they were both snobs."

Maibaum “felt that the studio people were in cahoots with Breen to delay production because they had doubts” and were unsure about Ladd’s audience liking him in an uncharacteristic role. Even after screenplay approval the studio held back for two years, using Gatsby as a carrot to make Ladd do more films, until he threatened to take a suspension.

The only trouble during production came when Ladd refused to kiss Betty Field. Had Betty offended him? asked Maibaum. No, said Ladd. “I’ll level with you, Dick. I get thousands of letters a week from my fans. Lots of them are kids. And I don’t kiss married women in my pictures.”

Maibaum stared incredulously. “But, Alan, you and I have dreamed about making this picture. For two years we’ve battled like hell for Gatsby. And you know as well as I do it’s a story about a man who tries to take a woman away from her husband.”

“I just know it’s wrong for me,” replied Ladd. “As an actor, I mean.” Maibaum argued for an hour but Ladd refused to kiss her.

"Despite studio fears, our version of Gatsby did well financially although the reviews were mixed. Critics differed much as John Farrow and myself had about Betty Field’s Daisy…Alan, for the most part, received surprisingly good personal notices. My own satisfaction stemmed from what Charles Brackett of sainted memory to all screen writers said to me: You’ve personally started a Scott Fitzgerald revival."

A few years back, I decided to start reading "great" American novels from a couple of 100 Best lists I found. To date I'm up to about 35-40 of them read. Of those most have read just "okay" to me, a few have read as "bad", several more hit me as "what the what?" Few of them seemed worthy of making a Best list. Among those few were CALL OF THE WILD and THE GREAT GATSBY.

I found Fitzgerald's novel every bit worthy of the high acclaim I'd read of it. Just a wonderful, magnificent book.

But...I am very much of the opinion that not everything has to be made into a movie. Some books, some plays, some TV shows, some historical events, should just stop there and stay there. GATSBY, for example, is not cinematic. It's pure literature and a movie whose aim is to simply tell a story is going to miss all that is great about Fitzgerald's work. (Oddly, the most cinematic book I've ever read, Richard Matheson's I AM LEGEND, has been filmed three times, none of them coming close to what Matheson achieved. I always thought that one wouldn't really need a script for I AM LEGEND. Just hand out copies of the book, red-pencil a line or two, and ya got yer movie.)

And this... "Trouble was the outfit not looking on me the way it had on Redford, being off a rack and anything but a tailored fit"... Well, yeah, that was our problem! The suit came off the rack so we didn't look like Robert Redford. Of course. That's the answer. That's the ticket.

I ran the 1932 LAW AND ORDER at Rochdale College in the 1970s. Part way through the movie four guys walked in clearly looking for trouble just as on the screen some trouble makers arrived. Walter Huston, as Frame Johnson (Wyatt Earp) sauntered over to the onscreen punks. He said, "'Pears to me you boys are looking for trouble." "That is a good line," I said to myself as I walked up to my troublemakers and delivered it. On screen the punks said, "Yeah, what are you going to do about it?" The punks I had to deal with echoed it. Frame Johnson said, "I guess I'm going to do whatever I got to do." I repeated the line. The punks on screen folded. The punks in front of me folded. Years later I got a copy of LAW AND ORDER on VHS. That moment is not in the VHS copy.

I'll go out on a limb and support THE GREAT GATSBY as the Great American 20th Century Novel. I've read it several times since college, some 45 years ago, still packs a wallop. It's ironic that ICE COLD COCOS, the supporting short is still extant, while the '26 version is lost.

Commander Cline:

What small town, where? Despite rumors the Redford version did okay in most settings.

The Vincent Price version of Richard Matheson's I AM LEGEND is the best for myself. I did not care for it when I first saw it. Like it more now.

The '74 Gatsby was perceived as a failure because of impossible hype and expectations. Critics were merciless and wanted to undercut it all. But I think it has matured like a fine wine. I saw it on first release and I didn't hear any crickets.

Rick put it perfectly -- "Gatsby" is pure literature, like "Catcher in the Rye". You can't put on screen what the authors wrote. The sign outside the ophthalmologist's office in the screen versions can't do justice to Fitzgerald's description. Plus, the characters themselves aren't nearly as interesting onscreen as they're described -- and Daisy is ditsy and annoying in the '47 and '74 versions. Neither time did I understand what Gatsby saw in her -- but I understood it in the book.

I ran the '47 version for my then 15 year-old daughter after she read (and enjoyed) the book. She found it nothing less than appalling, spending the entire time detailing what it got wrong.

Movies of great books are, at best, commercials for the books. The movie format is the short story format. 90 minutes, 120 minutes, 180 minutes is just not long enough to do any great book justice.I learned that early. A friend took me to see THE HUNGER. "What did you think?" she asked after. I said, "Wow!" She said, "Read the book." THE HUNGER is not GATSBY by a long shot but even a book like that falls short in the movie version. Ditto THE MALTESE FALCON and THE AFRICAN QUEEN. Those are perfect films for everyone who has not read the book. I will say that W. S. Van Dyke's 1934 THE THIN MAN equaled the book.

A curious note about the Redford "Gatsby".

When I was in high school in the early 1980s, we saw it in an English Lit class. But not from a film print.

Some educational materials distributor created a filmstrip and audio recording of pretty much the entire movie and that's how we saw it, spread out over two class periods.

I'd already seen the movie and thought it was rather dull. The filmstrip version, with a "ding" every few seconds to change to the next still, was almost unbearable.

But I loved the book when we had to read it for class and have revisited it a couple of times since then.

Fitzgerald's book is now in the public domain... so wouldn't Universal be free to do whatever it wanted with their Alan Ladd film now?

The book being in the public domain does not mean the film version (or any film version of a public domain book). Bram Stoker's DRACULA is in the public domain. The list is endless.

Obviously, the Paramount 40s film version would still be under copyright.

Even if the original novel has fallen into the public domain, Paramount might be limited in what they can do with the film based on the specific contracts they made with Fitzgerald or his estate.

The 40s version was based also on the Broadway show, meaning the playwright's estate would have to be involved, too. It's similar to why Olsen & Johnson's "Hellzapoppin" has never been officially released on home video in the US. Everyone involved likely thinks it's not worth the time or money.

Post a Comment

<< Home