Primitive Potions of Song Plus Film

Here Came Fifties Trouble --- Part One

Why more joy of late from Hot Rod Gang than The Wild One, Dragstrip Riot over Rebel Without a Cause? Or High School Hellcats preferred to Blackboard Jungle? Answer may be that old devil didacticism, which trio of A’s reek of, each to teach us eager-or-not pupils. Give me straight exploitation or give me nothing. The Wild One, Rebel Without a Cause, and Blackboard Jungle were, and remain, “problem” pictures, each to convey concern over social issues and do so “responsibly.” They remind me of lots being made today. I suffered through The Wild One and in fact, pushed accelerator through a final act, understood again why recall for most begins and ends with stills of Marlon Brando perched on a motorcycle with leather like what New York clubs later celebrated, his gang as threats distinctly non-threatening. Where wingmen include Alvy Moore and Jerry Paris, why not Joe Besser to bring up the rear? Brando’s was a delicate star mechanism. Most post-Streetcar saw him distinctly miscast. When was he 50’s bullseye apart from On the Waterfront? Brando, well his double, fist-fights Lee Marvin and Marvin improbably loses. There’s your verisimilitude. Nothing cries process like motorcycles in front of process. Worse though is Stanley Kramer to instruct, fun or potential for it bled out in service to civic betterment. Titles tell us such an incident happened (small town overrun by cycle hoods) but must never be permitted to happen again. Jim and Sam missed the lecture or chose to do opposite, because look at biker cycle they threw up upon sixties patronage, talk about never permitting such to happen again. After seeing Born Losers and The Glory Stompers, I would gladly have signed petition to achieve that.

Too much of mainstream presented youth from a parent’s point of view, as though hall monitors were producing entertainment for truant officers. Rebel Without a Cause might at least have recognized rock and roll as recent phenomenon, or forthcoming one, but did hidebound Hollywood know or care to acknowledge something still below ground? Rebel was heavily scored, effectively by Leonard Rosenman, this accompany to move Mom or Dad, classy crutch to dramatics heavy if not ponderously so (again, great music ... get the soundtrack CD with East of Eden). Of Blackboard Jungle, never mind. Anyone seeking reunion with bullies from school could get fill-up here, and lots evidently did, according to lush rentals. What was wanted, consciously so or not, was trash served same as Goobers from the snack counter or frankfurters at the drive-in, whips with which to antagonize parents who wondered what kids were coming to who'd enjoy these. Youth as worsening problem was fed too by discordant music they liked, rock and rolling a blight seeming to have landed all of a sudden. That wasn’t the case if one paid attention since wartime to styles merging toward a new but not really radical sound. Kids had been swing mad, dance mad, long before this, better behaved movies aimed toward them and their tribal habits. Universal in the early to mid-forties mass-produced teen musicals a world removed from what would come later from AIP and lowdown elsewhere. Gloria Jean, Donald O’ Connor, and Susanna Foster, let alone mass known as the Jivin’ Jacks and Jills, would seem alien had they dropped upon 1957 viewership, which by '57 they did, if only as oldies on television. I looked at, much enjoyed Mister Big (1943), and wondered how a culture embraced this, then devolved within a decade to something called Shake, Rattle, and Roll. Dance as art and spectacle had departed scenes, no more backflipping, lindy-hopping, jitterbugging … pleasure to share as grown-ups in fair enough shape could and often did manage such athletics too.

A lot of boys still boys came back from the war, aged in wood that was combat. They’d express a rebel spirit by dressing more casual than Dad, keeping on flight jackets or leather of whatever military issue to tinker with racer cars and two-wheel hogs. They also brooded and dealt with trauma left over from service, elders less quick to judge for what such seasoned men had been through. Good sampling via film was Guy Madison in Till the End of Time. Both he and Harold Russell in The Best Years of Our Lives return to boyhood bedrooms where pennants still hang and football trophies adorn dresser tables. Neither boy-suddenly-man will be the same again, even though being barely twenty in many instances, few to call them delinquent, not where debt for America’s freedom was payable so clearly to them. More complicated of vets went noirish route, in movies at least, while real life was more at Guy Madison speed, and for many who adjusted OK, at least on surface, speed was essence and expressed on dirt tracks and in garages where aggression could find at least superficially safe outlet. John Ireland has wheels to convey a restless spirit in The Fast and the Furious. Mickey Rooney drove fast, won trophies, and was sucked into a bank job by a wrongest dame in Drive a Crooked Road, a car culture beaut that didn’t need rock or roll or protest mechanisms to show change already here by 1954 when that film was released. Grown men gone wrong over ten or so years after peace could be attributed to what war had wrought, so in many instances at least, sympathy might attach. Offspring entering adolescence however was seen more as spoiled lot untested by service to country, hard times before their time, life lessons to guard against what now seemed bad behavior minus explanation or excuse.

Rebel Without a Cause was titled to a T, seen by some as license to whine, teens a threat to hard-won prosperity their parents would gladly share if only snarly brats would shut up and enjoy postwar bounty. Delinquents where age accurate were the more disturbing, Sal Mineo as Rebel’s crybaby a mystery no parent could divine, while overage bad “boy” Lee Marvin in The Wild One was comedic more than menacing, Marvin himself having been shot up on atolls approaching Japan and better put to grown-up criminality in The Big Heat. Sometimes it seemed Hollywood didn’t fully understand what a teenager was, other than stair-step down from Mom, Dad, family entering a cinema as families, way of life and living about to dead end. Here was reality junk merchants understood and exploited. It wasn’t for homespun brood to enjoy movies or music together. Lose these in terms of attendance, said vet biz observers, and trouble if not downfall of culture would ensue. “Mainstream” as desired state would be challenged on multi-fronts, this a threat to parents who couldn’t understand what had happened over seeming overnight, more so warning to an amusement industry termite infested, a broad and deep underground poised to scratch itchy kids with sound and furies no supplier with conscience would attach corporate name to, until it became a matter of doing so to survive. What seemed nature’s noise by way of music came slow and innocently as music styles converged to make what would be called rock and roll, or by cruder name, “rockabilly,” which was what rock and roll eventually separated itself from in order to be mass consumed. That mass would be tapped only through offices of mainstream manufacture, distributors that could get songs played and records distributed, not just in single cities or states even, but everywhere and all at once. Rockabilly would never cross such moat because large concerns would not permit it, all of like conviction that music must be controlled from the top down to be received by broadest of a US marketplace.

Rockabilly was just too scattered and strange to be acceptable. Most of what issued was from independent labels not likely to exist by same time a following year. They’d have less longevity than pterodactyls, but fresh wind blew through their sails, no corporate dictates to slow them or societal constructs to obey. Record producing was also font of opportunity, for near anyone could swing at it. A Lion’s Club member in your hometown that ran a furniture store might also be a music mogul … well at least a marginal mogul. Risk lay in recording and pressing platters, 500 to a thousand depending on plank you chose to walk and hope you’d not fall off. Faith in product came of instinct, yours and nobody else’s. Small businessmen produced from way back, jazz tunes captured in the twenties thanks to individuals who saw the coming trend and so rolled dice. A kid could walk off a street and get himself recorded and on local radio within a matter of weeks, days if he/she was lucky. Elvis got a break like this, others by hundreds following suit. Music makers could pursue their dream and independent impulse to at least regional success, the country still sectioned so that what did nothing in Detroit might rock solid in Milwaukee, difference often D. J’s pushing the platter or teens in one berg bopping contrary to counterparts in another. Rockabilly as synthesis of many styles meant no adhere to formula, however you’d define that in such wide-open time and circumstance. So much was so original that you knew it couldn’t last, not after big sharks sniffed gold in what they called kid stuff, but hold, kids now had money to fold. Rockabilly got its big lick through a second half of fifties busy with music vogues of every sort, adherents of each calling this or those years their “Golden Age.” Most have it easier just calling time they grew up a worthiest of all times (don't we all?), never mind what’s older and nix the new. Greenbriar gravitating to old could wish to have been there for initial burst of rockabilly and scratchy discs, scratchier voices, coming over radios, transistor or otherwise.

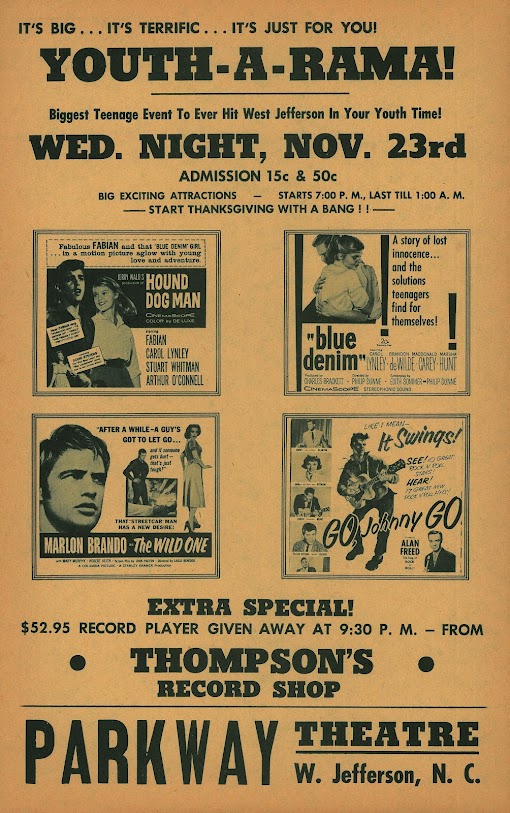

Heralds for rock and teen movie shows in Parts One and Two were creative

product of West Jefferson, NC exhibitor extraordinaire Dale Baldwin and assorted

showman manpower in my state. Imagine being on hand for such marathons as

these.

Thanks ever so to Scott MacGillivray for making it possible for me to see Mister Big.

Part Two re Rockabilly HERE.

5 Comments:

Born in the mid 50s, I remember beatniks giving way to hippies in movies and television. The pop culture industry was always dancing between mocking a new thing and trying to dilute and bottle it. Also, was a kid when discontented youth were not returning from a popular (or at least accepted) war but opposing an unpopular one. That was much harder to package than beats' rejecting easy symbols of conformity.

That "Youth-A-Rama" looks hilariously over-earnest -- even "Go Johnny Go" is weighted with drama between songs. For an all-nighter kids would want music, noise, laughs and pretty girls, without plots that demand full attention and certainly without melodrama about teen pregnancy, AIP movies, whatever else you can say about them, would deliver a REAL Youth-A-Rama.

It might be mentioned that the teenage market already existed in the early 1940s, because men were in the armed forces and women were in defense plants. This left mostly teenagers to fill seats in neighborhood theaters. The town of Milford, Iowa was one such example, and showman E. C. Arehart (reviewing a Gloria Jean-Donald O'Connor picture) reported, "Our age class that is left to attend shows surely ate this one up and no mistake. Some mentioned that they would like to see these two kids starred again."

Now I want to see Mr. Big (and pretty much any of those Universal musicals that I haven't seen/acquired). It's likely that we'll be running another one in Columbus next May (we did Sing Another Chorus this year).

Completely logical thought process. Never thought of that.

I grew up watching those Universal vest pocket musicals on local TV, usually tucked away in weekend afternoons. Loved those Donald O'Connor/Peggy Ryan dance numbers! Sixty years later these things seemed to have evaporated into thin air... don't know where to track these down! I have stumbled over a couple of 16mm prints of Universal B musicals over the years, but they're never the teen-targeted ones.

Post a Comment

<< Home