Third Act For The Marx Brothers

Post-war independent producers were a free-booting, often one-step-ahead-of-the-sheriff lot, Lester Cowan more artful than most dodgers who ensnared once major players eager to exploit postwar potential for windfall profit and tax advantage of do-it-yourself movie dabble. They'd supply backing for Cowan's known capacity to start and finish a project, his record an at-times distinguished one that so far yielded The Story Of G.I. Joe, Ladies In Retirement, and two of the W.C. Fields features for Universal. Independent producing was often a game called on account of darkness, at least for unwary participants who let themselves be lured into under capitalized, if not outright shady, ventures. Shutdowns were frequent, bank repossession of negatives not uncommon, lawsuits often dogging participants for years after release. Mary Pickford was experienced enough to know better, but idle afternoons at the estate she once shared with Doug weighed heavy, Mary willing from time-to-time to wade back in the game, as were The Marx Brothers, for differing reasons of their own. Result of this odd association was Love Happy, the Marx’s final act as a starring team in features. Groucho and Harpo would largely banish the film from their memoirs, no lingering upon a topic better forgot. Marx admirers to come found little worth defending in what most agreed was a slapdash mess of a show.

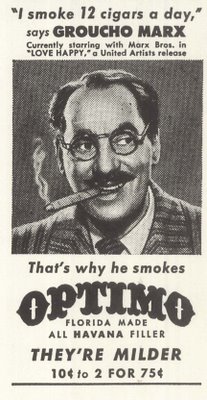

It started out as a Harpo vehicle written by his friend, Ben Hecht. Groucho always said Harpo had a Chaplin thing going, much as Jerry Lewis would later, Hecht’s treatment a tears of a clown sort that an age sixty Harpo angled for. Trouble was, no studio wanted in on rebirth of a post-Capra Harry Langdon, which seems to have been at least partial inspiration for Hecht. The writer saw Harpo as an ageless sprite, an imp of nature, the eternal Puck, plainly a Harpo nobody but Harpo (and Hecht) wanted. Somewhere along development lines, a debt-ridden Chico hopped the freight, and suddenly it looked as though a Marx Brothers reunion might be in the offing. Financing carrots were dangled, but only if Groucho could be induced to sign on. He was, and did. Mary Pickford’s involvement secured release through United Artists, and with three brothers on board, Lester Cowan raised the needed balance to start up. Initial pledge was for Harpo, Chico, and Ben Hecht to own fifty percent of Love Happy. To no one’s surprise, the money ran out before filming wrapped and a desperate Cowan resorted to a product placement scheme commonplace in today’s synergized industry, a concept barely explored by 40’s Hollywood. The idea was to run Harpo over rooftops for a chase finale, this the comedic backdrop for generous view of sponsor billboards. As the villains pursued Harpo, he would utilize oversized advertisements as visual gags, respective sponsors manufacturers paying Cowan for their goods in blinking lights. Mutual back scratch continued as Love Happy got prominent mention in print ads for companies dealt into the scheme. Exhibitors were annoyed by what smacked of payola, more so by the fact they weren’t in on the gravy. Trade mags spreading the word kept Love Happy off a number of screens.

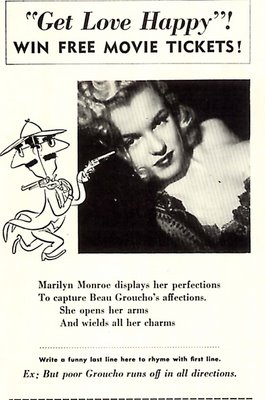

Domestic rentals for Love Happy were just over a million, not good news for claimants against Artists Alliance, Inc., Lester Cowan’s production company. Even less welcome was an uprising among the billboard backers. Cowan had taken $2,000 from the Fisk Tire Company upon his guarantee that Love Happy would garner an audience of fifty million, and the Gruen Watch people saw red when Cowan at a last minute replaced their agreed upon billboard with one for rival watchmaker Bulova. The reason was Lester piqued over Gruen refusal to advance $25,000 for his Love Happy ad campaign. Presiding judges set aside the timepiece merchant’s bid for a court injunction to halt showings of the film. Other matters before the bench included Groucho’s suit against Mary Pickford for his appearance fee of $35,000. By 1952, there was $765,000 in judgment liens against Love Happy (this according to Scott Eyman's excellent Mary Pickford biography). Even gentle Harpo took up the gauntlet when he walked up to Cowan, "the vilest man in the whole world," and spat in his face. Recovery was limited to a 1953 reissue, and later television sales. The reissue, with co-feature Africa Screams, brought back $106,000 in domestic rentals, much of that attributable to minute or so appearance by then-newcomer Marilyn Monroe, who was by 1953 was a very big star indeed. Her name and image would be prominent on all of Love Happy’s reissue art.

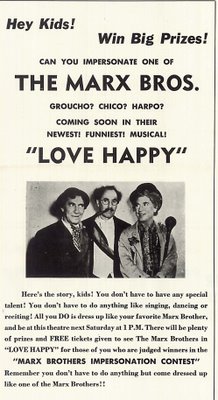

Essential problem with Love Happy was three Marxes being in it, just not at a same time. I don’t recall one scene with the team intact. Did letdown audiences imagine they were feuding? Love Happy seemed determined to keep the the Marx Brothers apart. Groucho opens the show from behind a private eye's desk, his mustache real and with thinning hair. He narrates in clownish answer to Philip Marlowe, re-enters the story from time to time until a final reel when he joins the action. Too little by then, and too late. Love Happy offers excess of Harpo, not enough Chico with Harpo ... they seem quarantined from each other as well. Worst of all, there is little or nothing of Groucho, who would seem ideally suited to at least disrupt musical numbers that make ninety minutes seem longer. Grouch’s scene with Marilyn Monroe is justly famed, but she’s on and off within a minute, long enough for effective publicity, as UA touted her plenty in 1949, a point when Monroe was barely seeing a start in pictures. Too bad there wasn't more of her in Love Happy. Villainy has a nasty edge. Melville Cooper takes harsh beating from principal heavy Raymond Burr as humorless Illona Massey looks on. Harpo is abused beyond humor's limit. This might have worked in Duck Soup, but now it is 1949 and we’re concerned for welfare of an aging clown who can take but so much punishment. What was left of Ben Hecht’s eternal sprite is disposed of in an awkward park bench exchange between Harpo and Vera-Ellen. If this is supposed to be an expression of unrequited love on Harpo’s part, maybe he should have solicited Chaplin’s guidance, or availed himself of a City Lights screening. The chase among neon billboards is by far the highlight. It’s fun spotting products, some still with us, others long discontinued, and Harpo makes imaginative use of them. A slender Paul Valentine, Joe Stephanos from 1947's Out Of The Past, has the unlikely romantic lead (he and Marilyn Monroe are "introduced" in the credits. There are Marx fans who will defend Love Happy. I can sympathize with them. It would take a stony heart not to admire troupers giving of their best at what they knew was twilight of long careers, at least in movies. To that extent, Love Happy is essential Marx Brothers. Perhaps it is where odds are greatest that we can appreciate best what made this team great.

5 Comments:

Love Happy was not happy for everyone, that's for sure. I am a "completist" when it comes to having their films so I look forward to adding this (and Copacabana) to my collection when they release it to the Shelves. That being said it is not a great film, but it is almost a post script with occasional high spots. Groucho said that the boys realized in A Night in Casablanca, during the filming of a stunt-laden climatic scene, that they were getting a bit long in the tooth for their trademarked antics, and Groucho himself was ready to draw the curtain. Solo projects were the name of the game for the brothers, and as far as I can gather - they respected each other's projects; Chico's band which toured in the 50s but never made it, Groucho's writing and You Bet Your Life, and Harpo's musical appearances and then we have Love Happy.

From what I can remember (and I will double check later- so someone correct me if I am wrong) there was no trouble between the brothers on Love Happy, just that the focus had been on Harpo, and the other brothers came on board later in the game for the reasons you mentioned. I believe by the time Groucho came on board to secure financing, the major of the film as originally envisioned had been shot. In order to bring Groucho in (and not reshoot anything, which they couldn't afford) they used him as a "bridging device"- thus Grunion was born.

Groucho does discuss Love Happy in some of his writings- particularly, if I remember correctly, Groucho and Me and talks about being involved in casting Marylin. Thanks for a great post!

Yet Groucho wrote his daughter, in 1947 or '48, of his plans to shoot "Love Happy" -- as if he and Chico were onboard from the get-go. I think all of them were so disappointed by how it turned out that they wanted to forget it completely.

I'd have bet the rent that a film with the Marx brothers and Marilyn Monroe, written by Ben Hecht, would be great.

And I'd have been sleeping on the street.

The film does come off rather better in a DVD from Republic[Viacom]with sharper picture quality and some bits that were missing from the familiar version.I'd love to find out why those scenes had been cut.

J.C. Loophole is, of course, the very capable host at "The Shelf", a site I enjoy reading each day. Thanks for your additional info on the Marx Brothers, J.C., and below is a link to "The Shelf" that everyone should check out ---

http://randomshelf.blogspot.com/

Post a Comment

<< Home