Final Trumpet Call For Raoul Walsh

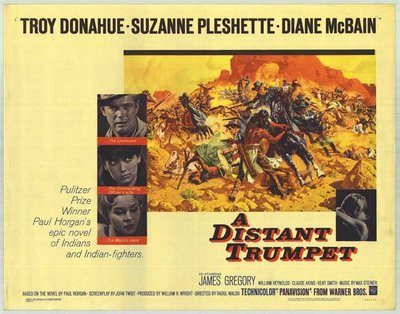

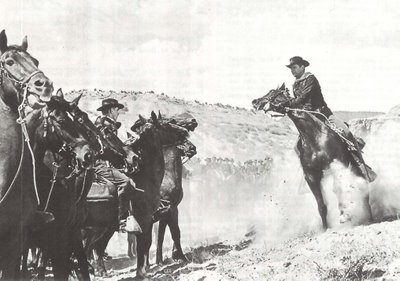

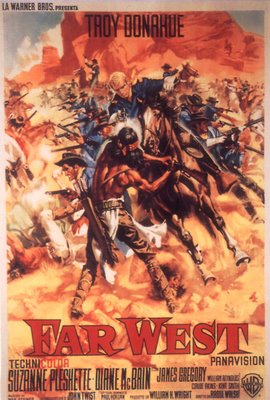

Final Trumpet Call For Raoul WalshThe great action director Raoul Walsh finished his career in 1964 with A Distant Trumpet, branded a "deadly bore" by New York Times critic Bosley Crowther, and damned with faint praise by Variety ("Youngsters are likely to respond to its vigorous image"). Crowther caught it first-run with Muscle Beach Party during a saturation booking that saw the combo playing all over the five boroughs. This was considered an appropriate berth for an old-fashioned western from a filmmaker everyone had taken for granted over a last several decades. Disrespect for A Distant Trumpet continues to this day. "Troy Donahue stars in this drive-in quality "B" western from the Warner Bros. backlot," says something called The All-Movie Guide in a single sentence review that manages to get something wrong in almost every syllable. What is "drive-in quality," first of all? Everything played drive-ins eventually --- Lawrence Of Arabia ran in 70mm on a few outdoor screens, so I don’t get this reference at all. Secondly, "B" westerns don’t carry a negative cost of $2.7 million. Finally, I can’t see where any of A Distant Trumpet was shot on the Warner Bros. backlot. The exteriors, and this picture is generous with them, were done on location in Arizona and New Mexico. It is a criminally underrated movie. There were weaknesses going in, and yes, Troy Donahue is one of them, but Walsh rose above all that and staged a remarkable farewell to fifty years of direction. DVD release from Warner Archive allowed me to see A Distant Trumpet for the first time in its original Panavision. Maybe I’m sentimental over Walsh, or composer Max Steiner headed for the end of his career as well, even Troy going through awkward paces shortly before Warner Bros. let him go. For whatever reason, A Distant Trumpet moves me. Noble last stands always do.

Raoul Walsh was born in 1887. This was 1964. He had done a film in 1915 (Regeneration) that challenged Griffith for directorial primacy. His silents include an enduring masterpiece of visual splendor, The Thief Of Bagdad, with Douglas Fairbanks, and The Big Trail emerged a first outdoor epic of the talking era. Action shows he made at Warners over a long period included The Roaring Twenties, Gentleman Jim, They Died With Their Boots On, Pursued, White Heat --- greats enough to challenge even Michael Curtiz for laurels at WB. Free-lancing in the fifties resulted in fine work we’re able to rediscover thanks to corrected ratios on disc --- The Tall Men, Battle Cry, Gun Fury, and The Revolt Of Mamie Stover. Walsh had disappointments later, but I suspect it was mostly others that fumbled the ball. Warners wanted him to direct PT 109, but President Kennedy had veto power on that selection, WB screening Marines, Let’s Go! for him instead of one of the good ones Walsh had directed, result a thumbs-down from the President. Maybe A Distant Trumpet was a consolation prize. In any case, it would be a large-scale production. Had the casting been less problematic, this might have been a western much better received (it ended up losing $374,000). Paul Newman instead of Troy Donahue would have been a start. Anybody would have been better than Troy, bless his heart, so why do I enjoy watching him in this?

Donahue represented the Herculean efforts of an army of Warner personnel. How do you get a performance out of this stone monument, wooden edifice, hopeless dishrag? Editors worked nights scrounging for usable footage of him during TV’s Surfside Six, while directors threw up their hands in despair at the sight of his name on call sheets (director of photography on A Distant Trumpet William Clothier referred to Donahue as "the stupidest man I've ever known in my life"). Delmer Daves was experienced (and ingenious) enough to prop up Donahue with character veterans for a series of overheated melodramas like Susan Slade and Parrish, but by 1964, Warners was ready to unload. There was much about the changing 60's culture that spelled obsolescence for a star of Troy’s type, and of Raoul Walsh’s kind of western as well. A Distant Trumpet would be followed within a few short years by ultra-revisionist Soldier Blue, Little Big Man, and the like. The notion of a heroic United States Cavalry would be forever put aside, Walsh and Donahue impossible relics in an industry dedicated to tearing down the sort of convention they represented. It was much the same for composer Max Steiner. Dynamic scores he did for a hundred Warner features seemed hopelessly quaint amidst a musical landscape soon to be overtaken by pop or folk tune wallpapering. Imagine Steiner stood before a junior WB executive prior to start of A Distant Trumpet and asked Have you scored a western before? This as Raoul Walsh at seventy-seven was beginning to lose sight in his good eye (the other lost in a 1929 motoring accident). He also had to put up with leading ladies Suzanne Pleshette and Diane McBain, neither prepared to sacrifice Vogue coiffing for the austere look of pioneering days. The director knew his game was up and made it known this might be a final encore. For Max Steiner, there was but a handful more scores (Youngblood Hawke, Two On A Guillotine, and Those Calloways). Troy Donahue did one more for Warners, then was set adrift in television or low-grade independents. By the time he turned up for a small part in The Godfather—Part Two, few even realized who he (once) was.

One good thing about Jack Warner still running the lot in 1964 was his willingness to entrust old-timers he had worked with over previous decades. $6.7 million permitted John Ford to do Cheyenne Autumn (which then lost $885,000) at a same time Walsh was heading up an expensive crew in the Painted Desert as though it were 1941 again. A Distant Trumpet was based on a novel by Pulitzer Prize winner Paul Horgan, but Walsh took more inspiration from They Died With Their Boots On, the Custer saga he had mounted years before. Indian/cavalry battles were depicted in the grandiose Walsh tradition. No one then or now could stage mass action with his kind of flair. Triangular romance and bureaucratic squabbling back at the outpost have a charmingly retro flavor --- you keep waiting for someone like Gary Cooper to walk in and straighten the whole thing out, even though Cooper had been gone several seasons by this juncture. Troy Donahue was what Walsh had to work with so he worked with him. Suzanne Pleshette would look back on A Distant Trumpet as "just another movie where I get Troy." Wonder if age and maturity helped her realize that she had witnessed not only the passing of an era, but one of its directing icons as well.

4 Comments:

CHEYENNE AUTUMN only lost $885,000? Good for JF! Most film historians imply that the picture failed to recover any of its costs.

I did a search on IMDB com on Troy Donahue...rather intriguing that he and Suzanne Pleshette were married in early 1964 and divorced that fall!

One note about Walsh directing Regeneration-- it was produced by Rex Ingram, already something of a heavyweight, so who knows who really did what. Clearly by the mid-20s, though, Walsh was a significant director; one would like to know more about some of those other films from his up and coming period.

And to say Walsh did more than any six other directors at Warners in the same time period... well, save for Michael Curtiz, who surely has the most impressive record. I think it's interesting, though, that the two of them blossomed at the same time-- something was really clicking at WB then. Walsh's work is like the mirror image of Curtiz's, showing us something different about each star-- Casablanca vs. High Sierra, Yankee Doodle Dandy vs. Strawberry Blonde, Robin Hood vs. Gentleman Jim.

John - I got the French DVD of DISTANT TRUMPET. Widescreen and fabulous sound. Maxie is happy!!! RPF

Post a Comment

<< Home