Ingrid Bergman --- Part Two

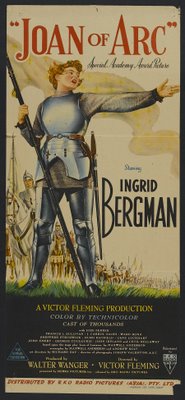

The jinx may well have set in before the Italian debacle(s). The charmed professional life of Spellbound, The Bells Of St. Mary’s, and Notorious placed Bergman on better marquees throughout the nation. We may not revere Saratoga Trunk, but it’s down on Warner books as one of their all-time profit pictures from that era ($3.4 million), and indeed, 1946 seemed a year in which an Ingrid Bergman show was playing around every street corner. So where do you go from the top except down? The Four Horsemen of Ingrid’s Apocalypse would ride in grim succession. Arch Of Triumph was 131 minutes of galloping pretension. Joan Of Arc was the role she’d obsessed on since making landfall in the US. Her Broadway triumph as Joan Of Lorraine suggested a warm reception for a movie adaptation, but cost overruns on the independent production (in which she was a participant) made Gone With The Wind look like something out of Monogram. Were it not for the $4.5 million spent, Joan Of Arc might have had a major pay-off, for crowds responded to the tune of six million in worldwide rentals, but reviews were spotty and viewers were bored. Bergman had been intimate with director Victor Fleming (he of a previous assignation with Clara Bow), but the veteran director dropped dead shortly after Joan was completed, some guessing he’d succumbed from the stress of it all. Under Capricorn was Hitchcock being experimental --- this was his run at independence after suffocating years with Selznick. He and Bergman were alike for having plowed fields for a producer who then harvested the bounty, but neither were equipped to administer production on their own, where one disaster could ring down the curtain on a whole company. Hitchcock had his with Under Capricorn, while Bergman finished her quartet of losers with Stromboli, a would-be art movie born with a gushing fan letter to its director, Roberto Rossellini, and ending with Ingrid’s career in ruins.

Post-war European filmmakers had to shoot in the streets for lack of indoor facilities, their stages having been blown asunder during the conflict. (Extreme) austerity makes naturalists of us all, and directors like Rossellini had little choice but to take to the sidewalks with non-professional casts and shoot whatever took place there. Pampered Hollywood was stunned by the harsh realism, and audiences responded to gritty, gloves-off pictures like Open City and The Bicycle Thief. Roberto Rossellini was the (apparent) autuer behind the former, and when Ingrid Bergman caught Open City in a New York art-house, she swore to one day work with the genius behind it. The Italian director had already negotiated with Selznick, who was himself impressed with neo-realists, and would indeed support future projects involving Euro talent, but Rossellini was too capricious and disorganized for even this producer’s taste, and their talks soon broke down. Bergman’s aforementioned letter was simple and direct. She’d come to Italy and work for Rossellini if he’d have her. This was opportunity banging loudly at his door, and Roberto was quick as a flash to arrange a meeting. Clueless Petter Lindstrom bade enter to the director, who then conducted a campaign of professional (and personal) seduction while a guest in the man’s home. By the time Rossellini left, he had Bergman in his pocket. Stromboli would be their first collaboration. There was no script. The cast was filled with interesting faces so beloved of the director, but none of them were actors. Its volcano location was nearly inaccessible, and an indecisive Rossellini frittered away weeks dreaming up something for the cast to do. Turns out capable assistants (including Frederico Fellini) were largely responsible for the stories that had made Rossellini’s previous pictures work. Without them, he was floundering. Bergman was beginning to realize this was an emperor without clothes, but he’d deftly talked the actress out of hers, result a pregnancy out of wedlock (with him anyway) and a ravenous press poised for a slow kill.

Worse luck, her business manager had been systematically robbing Ingrid back in the states, and by the time anyone caught on, he’d taken the gas-pipe and left her stony. Husband Lindstrom set upon a vindictive course, and turned their daughter against her. Joan Of Arc was suddenly a devil incarnate, and broke besides. US exhibitors cancelled Stromboli bookings after her child was born in Italy. Rossellini married her in the wake of the divorce, but made it known she’d not work for directors other than himself. Senate members suggested her visa be picked up, a matter of little consequence in light of press so foul she’d not enter the US in any case. Bergman was restricted, if not condemned, to Rossellini films from here on, each one a step down from the previous. The visionary of Open City was spending money and racing about in Ferraris while debts piled up. What movie deals he got were owed to his wife’s diminished prestige, and what grosses they earned were restricted to the continent, as Bergman were strictly poison in the US (a 1954 re-issue of Saratoga Trunk took just $110,000 in domestic rentals). She’d be thoroughly deglamorized in bleak Rossellini projects he imposed upon her, not so bad an idea in itself were he not so intent upon it. Europa ’51 went nowhere in Europe or the Americas, and Viaggio in Italia was a more-or-less ad-libbed domestic drama with George Sanders, who was unflappable in most circumstances, but Rossellini’s lack of preparedness gave even Sanders a nervous breakdown. The latter was shot in English language, so it’s at least marginally more accessible than the others, and Martin Scorsese has been an eloquent champion of these films in his documentary, My Voyage To Italy, so there are clearly values here worth exploring. Too bad no such defenders arose when they were new, for the unhappy end result was a near-total creative collapse for Rossellini and years of career stagnation for his wife.

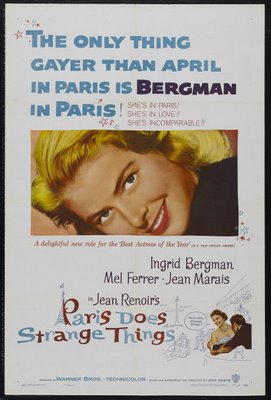

There had been feelers from Hollywood. George Cukor wanted her for a project, and others were anxious to assist in a comeback, but Rossellini nixed all such overtures. An actress with Bergman's gifts would stay caged but so long, however, and by 1956, she was ready to break out. Tea and Sympathy would be a stage comeback, followed by collaboration with noted director Jean Renoir, whose Elena and Her Men was perhaps too French for domestic palettes, but did at least suggest there was a star waiting to be reborn. It was released stateside as Paris Does Strange Things, but Warners collected a peaked $185,000 in domestic rentals, scarcely enough to justify the import. The original French-language version remained largely unseen until Kino released a stunning DVD last year, which showed this beautiful color production off to its best advantage. The real breakthrough was Anastasia, and that resulted in an Academy Award, so obviously all was forgiven. Indiscreet reunited Bergman with Cary Grant, who’d stuck by her through the bad patch, but time and stress had aged her beyond those parts that brought glory a decade before, and a new generation of leading ladies had emerged besides. She was a prestigious name for infrequent television appearances, but none of these features could put her back in a winner’s circle --- Goodbye, Again, The Visit, The Yellow Rolls-Royce --- too much momentum lost, and now she was firmly identified with old Hollywood. There was a comeback in the form of another Academy Award for a character role in Murder On The Orient Express, and distinquished work along these lines continued through the seventies. Memoirs were inevitable, and hers were more dignified than most, but in how many interviews can one explain what it was like working with Humphrey Bogart? She made a final TV-movie while gravely ill, having never lost the indomitable will to stay in harness. She died on her sixty-seventh birthday in 1982.

Photo Captions

Color Publicity for Selznick

Ingrid Bergman as Broadway's Joan Of Lorraine

With Cary Grant in Notorious

Holding a pivotal key in Notorious

Fan Magazine Color Portrait

Australian Poster for Joan Of Arc

With Joseph Cotten in Under Capricorn

Another Color Fan Mag Portrait

Stromboli

With Yul Brynner and Helen Hayes in Anastasia

One-Sheet for Paris Does Strange Things

4 Comments:

Re: Bergman's later career-- didn't she win the academy award for 1974's "Murder on the Orient Express"?

I agree with jadm -- your otherwise fine account implies that her active career ended in the days of THE YELLOW ROLLS ROYCE. After all, Bergman continued to do striking, successful work in features and television until her passing in '82.

It's worth noting that when she finally did return to Hollywood to appear in a picture (her post-Rossellini films were made in Europe), it was a hit -- I still remember my father telling the whole family back at Christmastime '69, "We're going to see Ingrid Bergman in CACTUS FLOWER!" All right -- it wasn't her finest hour, but she was funny, more than holding her own with Matthau and Hawn. The theatre was packed, too.

I still fondly recall her charming, sheepish acceptance speech for her 1974 Oscar for ORIENT EXPRESS, which remains possibly the only Academy Award speech in which the winner pretty clearly suggested that this time the Oscar had gone to the wrong actress -- Bergman even seemed a little stunned that Valentina Cortese, nominated for Truffaut's DAY FOR NIGHT, hadn't won. [Bergman had earlier won the 1974 BAFTA for ORIENT EXPRESS; Cortese had won the 1973 BAFTA for the Truffaut film.]

I believe it's safe to say, though, that Ms. Bergman understood that this particular Oscar was an tribute to "Ingrid Bergman" -- her thanks seemed heartfelt and most gracious. [She probably deserved yet another Oscar for her later work in AUTUMN SONATA.]

Right you are, Griff. Bergman deserves more credit for the work she did late in life, including the "Orient Express" part. I'm only sorry she missed out out on so many starring roles during the exile. There just wasn't much time left for leads before she had to move on to character parts and TV movies, though she was awfully good in those.

John - As always, a wonderful post. Thank you! I tracked down a great quote from Sidney Lumet about Bergman on Murder on the Orient Express. I like it because Bergman always was a smart actress, not just a talented actress.

Lumet said:

In "Murder on the Orient Express", I wanted Ingrid Bergman to play the Russian Princess Dragomiroff. She wanted to play the retarded Swedish maid. I wanted Ingrid Bergman. I let her play the maid.

She won an Academy Award. I bring this up because self-knowledge is important in so many ways to an actor.

Post a Comment

<< Home