Monday Glamour Starter --- Mary Astor --- Part One

Monday Glamour Starter --- Mary Astor --- Part OneMary Astor seems to have been born mature. I cannot recall her as an ingenue or girlish romantic. She’d had a career with that sort of thing in silents, but by the time talkies arrived, the girl/woman/matron phases had been seemingly traversed and it was now possible to cast this twenty-six year-old actress as the wife of George Arliss and Erich Von Stroheim. That worldly-wise, if not world-weary, expression conferred an authority her thespic peers could only dream about, but to hear Astor tell it in her excellent Hollywood memoir, A Life On Film, she was merely going through the paces like any other minion on the set. Having just watched The World Changes and Easy To Love, both from her early thirties Warner period, I would argue she’s far too modest, for these performances are second to none among those I’ve looked at from said period. Indeed, I don’t know of any movie that hasn’t been richly enhanced by her participation in it. Mary Astor always conveyed a sense of having lived in the real world, as opposed to those who were just play-acting. When she came through the sound-stage door, she brought an aura of reality with her. A lot of that may have been the luck of a face that bespoke experience, or a manner that suggested past hopes ended in disappointment. Either way, Astor made you believe in whatever emotion she was selling, and even if this were only walking through a performance in her mind, it never came across that way onscreen.

This time it was the father who did the pushing. He was one of those high-flying types forever coming aground with harebrained get-there-quick schemes (He thought big and failed hard, she remembered). Dad’s daughter-marketing had been preceded by an attempt at raising mushrooms in the cellar and investments in far-off walnut groves. He was the real-life W.C. Fields of grandiose business aspirations that would rescue him from anonymity, only Mary’s father didn’t share Bill’s benign onscreen regard for his offspring. Otto Ludwig Wilhelm Longhanke seems to have embodied Teutonic tyranny as it’s so often depicted in movies, and the mother ran him a close second exercising suffocating parental authority. Mary couldn’t go to a bathroom unescorted. Even as a silent luminary of some renown, she had to share sleeping compartments with both of them when traveling. It took a determined rescuer to loosen those filial bonds, and John Barrymore, being a seasoned connoisseur of teenaged innocents, set himself manfully to the task. Mom and Dad weren’t such fools as not to know what was going on during those private afternoon rehearsals at J.B.’s hotel suite, but they were certainly practical enough to recognize how they might profit by the forfeiture of Mary’s virtue. Leading lady status opposite Barrymore in Beau Brummel rewarded their relaxed vigilance, and attendant salary hikes put daughter and loving parents in a new house which they insisted be titled in all three names.

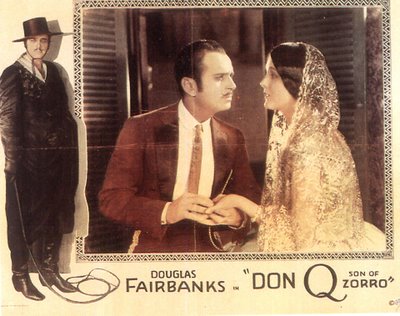

A Life On Film removes several layers of glamour dust we associate with old Hollywood, Mary Astor having got tired of it all pretty quick. Her silent emoting was, by her own admission, little more than going through trick-dog motions while thinking about that night’s supper menu, but even Mary took umbrage at the foolish antics of repeated co-star Lloyd Hughes, himself so embarrassed by leading man duties that he constantly undercut love scenes with japes and wisecracks. Stardom in those days was no easy adjustment. How many had gone before to mark the way? In this infant industry, up-and-comers were ill prepared to handle such wealth and adulation. Mary got a cold splash when the once ardent Barrymore gave her the go-by in favor of Dolores Costello, and this just as they were embarking upon Don Juan in 1926. Other than the two Barrymores and a turn with Douglas Fairbanks in Don Q, Son Of Zorro, her silent work is largely unknown to us now. Indeed, she may have drifted out with the tide of so many other voiceless headliners were it not for an LA stage venture that got her noticed by talkie-obsessed producers looking for faces who could also speak. That local play was what saved her, for Astor had earlier made a sound test at Fox suggesting a too deep, masculine inflection, and the fallout might have scuttled her career but for the live performance. Now she was steeped with dialogue, and there were four talkies in 1930, followed by seven more the following year. Most were with RKO, where she had a brief contract, but few amounted to much. She noted later the unreality of her life --- riding about in open roadsters swathed in furs as the rest of the country sank into Great Depression. Movie stars like Astor spoke among themselves about the business and nothing else. No one had any interest in the personal lives of the other, except inasmuch as it related to movies or their career. Genuine friendships among these people were virtually unheard of. Everything was about appearance and maintaining it. No one had to look at breadlines, but knew they were out there.

In A Life On Film. Mary Astor describes eighteen of the initial talkies as having been unworthy of her time and ours, but a look at that credit list from the early thirties reveals a lot of hidden gems she underestimated when that book was written in the late sixties. It’s hard to come away from these Warner pre-codes unimpressed --- A Successful Calamity (typically excellent George Arliss vehicle), The Little Giant (saucy gangster spoof with Edward G. Robinson), The Kennel Murder Case (glorious culmination of Bill Powell’s Philo Vance series), The World Changes (she does a mad scene that’s truly frightening), Convention City (if only I could comment on this one), Easy To Love (I laughed till I cried --- honest), Upperworld (how can anything with Warren William be less than triumphant?), The Man With Two Faces (Eddie G. again), The Case Of The Howling Dog (first of the Perry Masons), Page Miss Glory (deco time capsule, and a treasure). What actress wouldn’t revel in a filmography like this? --- but bear in mind, Astor’s career memoir was written nearly forty years ago, long before appreciation for such programmers came into flower. If she could have looked at them again, there might have been a reappraisal, but it’s enough that we can enjoy them all today. Outside Warner gates, she kept distinguished onscreen company. The Lost Squadron found Astor joining ranks of abused wives for Erich Von Stroheim. Red Dust was a classic even she acknowledged in A Life On Film, and may have been the last time Astor unleashed passion behind a cool exterior. Maintaining stoic maturity relieved her of conventional leading lady duties for a most part, and by the mid-thirties, she was in a class virtually by herself. Too bad there weren’t more leads for actresses with such unique ability. From here on, it would be a matter of stealing limelight from those billed above the title. Audiences seeing her name down in the credits realized Astor would often as not be the one they’d remember.

Photo Captions

Mary Astor with John Barrymore in Beau Brummel

Lobby Display from Don Q, Son Of Zorro, with Douglas Fairbanks

One-Sheet from Second Fiddle, presumably a Lost Film

Lobby Card from Two Arabian Knights (it's been shown on TCM)

Dramatic pose from Don Juan

With George Arliss in A Successful Calamity

With Erich Von Stroheim and Richard Dix in The Lost Squadron

With Edward G. Robinson in The Little Giant

With Jean Harlow in Red Dust

With Warren William and others in The Case Of the Howling Dog

With Warren William in Upperworld

Part Two of Mary Astor is HERE.

1 Comments:

Another excellent blog. I wonder sometimes at actor/actresses' when they say some of their work was menial and not of importance. I think pehaps their reputations(perhaps built in later years) make them believe that anything below a certain "artistic" merit is of no importance and unworthy of them.

Post a Comment

<< Home