Step Up Rangers!

Buck Jones As Guiding Light for Generations

“Critic’s Choice” has out a DVD of nine Buck Jones westerns produced by Columbia in the early thirties. My question is, what critics chose Buck Jones for a 2021 disc set? He is gone as gone gets. Even those who profess to love old films go blank at Buck’s name. All of B westerners are rode off for that matter. It may be time for me to shut up about them ... maybe had they been less integral to past collecting, I’d step off and let memory of cowboy dominance drop. Those after all were not my memories, but ones of old men who guided me through thicket that was film and paper chase once upon past time. Again it was question of whose nostalgia was this? Not mine surely, even as I long to have been part of generations that saw cowboys and serials on initial roundups. Old timer enthusiasms really were contagious, but thing was, if you didn’t live it, you couldn’t truly love it. I always felt a little left out at cowboy cons, as if they all had secrets I never would know. And surely no one in my age group cared for clip-clop westerns … they could barely be bothered with westerns at all, lest they were Italian and had Clint Eastwood in them. Question just occurs: Did any college or university ever screen a B western? (Take your time, we’ve plenty of it) Closest they may have come was in the seventies when Clayton Moore visited campuses as the Lone Ranger, but that was more TV nostalgia than front row feeling. There was something mildly inauthentic about tube cowboys, mere toothpaste to squeeze out each week between jarring commercial breaks, no more reflective of the old west, or even old westerns, than lunch boxes that bore their likeness. Cruel was passage of time that saw cowboys disappear, then fans to fade the same. What film scholar will claim these now?

I want to talk about Buck Jones for few others that are likely to. Per usual with lecture, I brought slides, plus watched some of what he left, feature/serial samples, to better understand how this man commanded loyalty likes of which few of any genre would inspire. But this was love of then, to sustain no longer than lives of devotees. When Buck died tragically in 1942, there was grief not limited to child patronage, for he had been around and performing since the early twenties, sufficient to engage one generation, then a next. Longevity of film stardom was a thing not realized until lifetime of movies caught up with lifelong popularity of players who stayed the course. Age or fate would claim a Buck Jones, or Gary Cooper, or John Wayne … otherwise they might still be here selling tickets, with help of digital jiggery I’ve seen applied to Al Pacino, De Niro, more lately Eastwood, judging by a trailer for Cry Macho, his latest starring vehicle, the seeming impossible made possible for a man aged ninety-one playing “Macho” as he has since I was born (so maybe it's my turn to go out and be a leading man). Will digital bring Bill Hart back? I mean not his old movies, but a reanimated him. Or Buck Jones? No good, because wizardry however adept could not restore what they stood for, or a world they bestrode. Anyhow, Bill or Buck would probably take one look at a world we’ve made, and say Thanks Pard, but No Thanks.

|

| Buck is Guest for Recital of a Buck Jones Rangers Band |

Buck Jones had been a real cowboy in Oklahoma, this after serving in the US Cavalry, entry papers faked (with his mother’s assist) to effect he was eighteen rather than actual sixteen. Buck was shot in the Philippines trying to put down the Moro rebellion on Army behalf, nearly left a leg there. He could ride a horse as wind blows, agreed to try acting so long as it amounted to no more than rugged stuff he was doing anyway. Silent hoof-beating for Fox got him to number two at the studio behind Tom Mix, and by twenties end, he was earning $2,500 a week, which at that time bought much cake and ale. Jones was a man of moderation, bent toward family and seeing jobs through. What he lacked was business acumen and ability to spot snakes in his grass. One of them wheedled him into a Wild West show Buck underwrote after leaving Fox, and poof went the cowboy’s fortune. He took after said snake with a gun, but like all knaves, this one vanished truly into the night, passage bought with Buck’s hard-earned fortune. What was it with western stars fronting Wild West shows and circuses gone splat? What chance did any greasepaint cowpoke have of hauling tents, livestock, clowns, and popcorn back/forth across rugged country that was still America up to and through a Great Depression? Blind optimism I suppose, and boy, were these heroes blind, like rubes challenged to find peas under walnut shells. Their talent lay spectacularly elsewhere. Men of Buck’s sort were seldom put among us, them of ability foreign to virtually all who acted for screens. In his and their case (Mix, Maynard, too few others), it mattered not how dialogue was spoke, or anything done standing still. People who went to see a Buck Jones had no interest in inertia.

|

| Here and below: Some of What You Got With Your Buck Jones Ranger Suit |

Fans loved cowboys because they were the only ones taking real chances at otherwise make believe. Children especially knew hazard duty when they saw it. I looked at a chapter of Gordon of Ghost City (from VCI in HD) where Buck does a horse to wagon transfer, as in under the wagon and between charging team, to hoist up and rescue Madge Bellamy. Cold chill watching? Yes, and largely because action like this seems no longer attempted, latter-day superheroes anything but super beside Buck and brotherhood who really did danger as opposed to floating about in computerized space. Other instance: Buck bulldogs a man off his mount and they fist-scrap, not on choreograph terms to come courtesy Yakima Canutt who knew how to make fights look real without being real, but with punches to the face and elsewhere not necessarily pulled as Canutt and company would master later. Reduced circumstance as befell Buck by the early thirties cut pay packet to $300 per week, from which he was honor bound to repay debts from the kaput tent show (my query: Did he ever track down that snake who stole?). Thing is Buck seldom played stalwart as in hero blueprint pervaded by others later in the decade. Jones often as not arrives broke and hungry, chased off ranch hand jobs for slacking, or in the case of Forbidden Trail (1932) handy with a slingshot and too bone idle for useful work. Buck employed humor as much as action; you could never be sure he’d make it to the burning cabin on time or even be inclined to do so. What we call “commitment issues” were written all over Buck. He made bumming around a signature, and I wonder if the character wasn’t based on observation Jones made of men who in hard times said Why Bother?, figuring to give little as they could for as much as they could get, except Buck gave all once roused, the wait always worth it as he would exceed whatever was expectation.

|

| You Can Hear It at You Tube. Nice Banjo Accompany. |

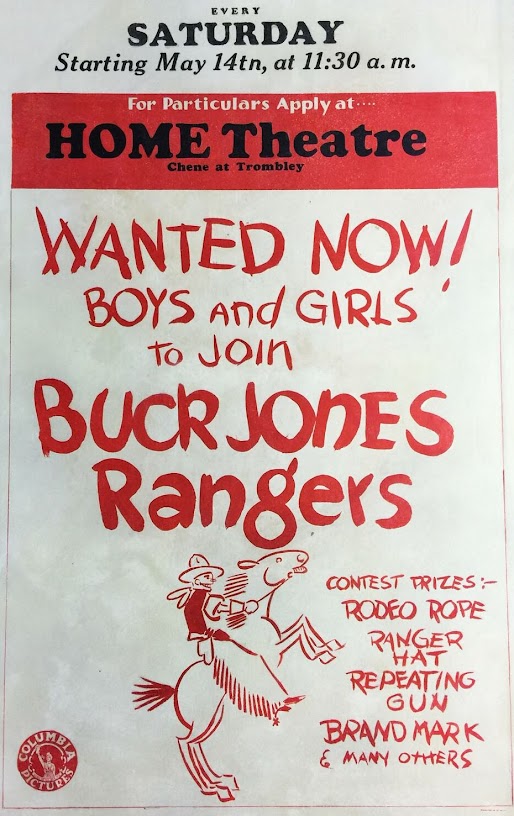

So it was for something other than conventional heroics that Buck Jones’ devotees looked up to. Columbia initiated the Buck Jones Rangers in 1932, a logical outgrowth of Mickey Mouse Clubs which had been in place and successful for several years. The Rangers were organized and prolific. Membership estimates were from two to four million, cooperation had from Parent-Teacher groups and the Boy Scouts of America. Girls were welcome to become Rangers. Club chapters were dotted nationwide. “The Rangers keep the theatre-owners out of the red and help him to greater profits. It means that a nationwide organization of enterprising boys have endorsed your theatre and are out boosting it. The volume of such exploitation cannot be estimated. Every exhibitor owes it to himself to see that his theatre is designated as the home of a troop of Buck Jones Rangers.” Nat Farber’s Majestic Theatre (NYC) announced formation of a chapter and saw 2,500 children sign up within a week. To celebrate, he staged a parade through the heart of upper Manhattan where Rangers were joined by two Boy Scout troops and a Bugle and Drum Corps. Arrival at the theatre saw all participants reciting Rangers’ and Scouts’ pledges. Buck Jones committed to teach Rangers “everything a cowboy knows,” including how to throw a rope, ride a horse, and “shoot dead straight.” There was ranking among Rangers, chevrons issued to reflect individual status. Depending on individual achievement, you could become a First-Class Ranger, Corporal, Sergeant and so on up to Assistant Chief and Chief.

Ranger tunes had lyrics customized for members (theatre singalongs a weekly tradition), plus Buck gave tips on how to learn the harmonica and bugle (“almost anybody can master these instruments immediately”). Instruction was offered to help members become expert western “story tellers,” with a book explaining “how you can work out many thrilling western tales for yourself … The book gives all the parts and the plot and dialogue.” Did Rangers grow up to write for series westerns? Looks as though they were being groomed for it here. Single-round boxing matches of three-minute duration were organized for one chapter. Another event saw 15,000 Rangers turned out for a picnic and swim event at Luna Park on Coney Island. A Rangers Rodeo drew 10,000 to bleachers. Obvious benefit for Columbia was enhanced by chapters operating independently, none relying on the company for financial support. The Buck Jones Rangers had become a self-perpetuating force, “the biggest fan club in America,” as one exhibitor labeled it. No western star, save Tom Mix with his talkie series for Universal, came near popularity Buck Jones enjoyed. Among Columbia westerners, Jones regularly outpaced, for instance, Tim McCoy, The Thrill Hunter (Jones) taking $100K in domestic rentals, while End of the Trail (McCoy) saw $65,000, money not so dazzling as A’s done by Columbia or elsewhere, but reliable, plus bear in mind, the pictures themselves cost in low five figures, patronage in many if not most situations paying mere dimes, at most quarters, to see them.

|

| Have Yet To Come Upon This Scene in Gordon of Ghost City, But Will Keep Looking |

Jones had signed with veteran producer Sol Lesser for the initial eight talkie westerns to be distributed by Columbia, a point at which $300 per week looked good, at least on Depression era terms. The star’s stipend rose as cheer-led by Ranger ranks swelled via merchandising to meet need of boys and girls who sought to emulate Buck. Consider the Rangers Cowboy Suit, with hat, kerchief, lariat, other accessories, then imagine going to-fro for Saturday shows, becoming one with Jones as role model. There was singular state of mind inspired by cowboys, a philosophy complex as way of life proposed by Transcendentalists of an earlier age (left-field notion which I'm more and more believing). These were children who would grow up and win a next World War after all. How much may we credit Buck Jones and men like him for this? To think series westerns were simplistic is to reveal too little familiarity with them. They would not have lasted so many decades, gathered such mass support, had water been shallow as detractors propose. I had an encounter just recent with a townsman now in his late seventies who worked as an usher at the Liberty during the late fifties-early sixties. Colonel Forehand hired a lot of boys that he knew could use the work, and their families the income. One stipulation however: Each of ushers had to present his report card whenever schools issued them, continued employment dependent upon keeping up your marks. I have gone years seeking to understand the cowboy credo better, when perhaps there was no better testament to it than policy like this. The Colonel upon retirement became scoutmaster for our Presbyterian Troop 336. More Eagles came of his stewardship than any the troop had recorded. Like other small-town theatres through the Southeast, the Liberty went decades supplying life lessons on Saturdays via cowboy instructors. I know I’m the poorer for not being there for them. Maybe attendance at all those collector caravans was effort by boys-to-men to finally understand what it was about westerns and idols populating them that made matinees teachable moments for so many.

|

| Slow Period in the Dealer's Room at the Seventh Annual Buck Jones Meet in 1989 |

Years ago, I guess around 1977, some of us drove to Greensboro, a local theatre rolling weekend dice with westerns just like in Good Old Days, except this was no downtown house crowded with kids, but a strip mall cracker box sat empty except for us. Management surely recalled better days from youth, but these would not be recaptured by 16mm prints, fuzzy and muffled, of John Wayne in Riders of Destiny, along with Buster Crabbe and Bad Fuzzy St. John in something-or-other. You Can’t Go Home Again should have been writ large upon the marquee for these and other of heroes ridden away to stay. Buck Jones was then gone thirty-five years, a lifetime by ’77 reckoning, him a most notable of 492 fatalities from 1942’s Coconut Grove fire in Boston. The Rangers had meantime hung up spurs, a Rochester, NY fan, Dominick Marafioti, of Rochester, NY, reviving the concept in 1979, his annual Buck Jones Festival running till 2004, when Marafioti left us, after which there was no one to take over the Festival. Celebration of series westerns fell like dominoes. To my knowledge, there isn’t a round-up left going. Jon Tuska and Packy Smith, stalwart among western historians, have passed. I found a Buck Jones Rangers of America ball cap on Ebay, ordered it, and will await some hombre asking me who hell Buck Jones is. Meanwhile, I watch his westerns. One from the Critic’s Choice set was Range Feud (1931), wherein sheriff Buck’s boyhood pal, who he must now take in charge for murder, is played by boyish-still John Wayne. Latter was said to idolize Jones, “a genuine hero” said Wayne, because he sacrificed his life saving others at the Coconut Grove. There’s little indication it went that way, but I, like Duke, will gladly cling to Buck as real-life hero to the last. A lovely scene that opens Range Feud will do to sum up Buck Jones as first among exemplars. He speaks to warring cattlemen from the pulpit of a frontier church, pistol drawn to keep factions from pulling theirs. “Remember … we’re in the House of God,” says Buck, as sincere a line reading as one could hope to hear. Dedication of those kid multitudes, of adults they would become, make plentiful sense by such evidence as this.

UPDATE (8-31): Scott MacGillivray presents evidence of Buck Jones' appeal to an older and younger generation circa 1941:

Hi, John — In today’s post you say, When Buck died tragically in 1942, there was grief not limited to child patronage, for he had been around and performing since the early twenties, time enough to engage one generation, then a next. Longevity of film stardom was a thing not realized until movies were around long enough to confer lifetime popularity upon ones who stayed the course.

Right you are. Here’s a trade ad for the penultimate Buck Jones serial, and Columbia is reminding exhibitors to aim for both generations. (The kids’ hats aren’t anachronistic — the serial was released in January 1941, so this is a winter scene!)