Hands Off Settled Story Classics

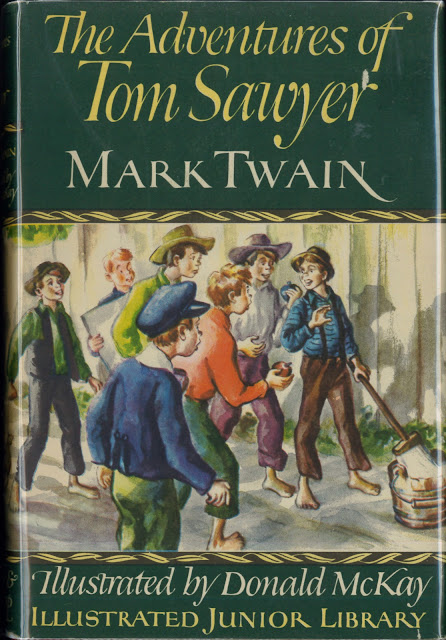

Where One Critic Played Safe

Among reviewing cliches is assurance an author would “spin in his/her grave” to see what movies did to a novel, as w/ Otis Ferguson re The Adventures of Tom Sawyer in 1938. I enjoy this critic a lot, but here as with others he bowed to expectation that, of course, any film, let alone one produced by Selznick, and on lavish scale, would profane “a classic,” sacred past work defiled per usual. Certain base rules were observed, now as then. Imagine coming out of Hamlet to say, thank goodness they cleaned up that mess of a play. Reason the issue lured me was an “Illustrated Junior Library” printing of Tom Sawyer, dated 1946, colorful illustrations bespeaking the 40’s as much as 1875 when Mark Twain’s book was published. I read it as a boy, saw screen versions, so noted departures each took from 305 pages of text. Takeaway was this: Selznick’s adapt improved on the novel, at least so far as structure and pace. Had he followed it faithfully, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer would be unwatchable. How long since Otis Ferguson’s last read, or did he break spine upon Mark Twain’s original at all? I think Ferguson’s review was pure reflex, words he was expected to write, and so wrote them. Brave critics part from the pack, but all know greater comfort of going along to get along. Here was once where Ferguson gave in to keep his place at colleague tables, the first time I was disappointed by a column of his.

When did Tom Sawyer become sacrosanct, or was it ever so? Mark Twain wrote in lurches, a start made, then two years before taking up Tom again. Sections were done as they came to the author, ideas spilt upon paper, then wait “for the tank to fill up again.” He took another year off after half was completed, the draft then dispatched to friend and fellow author William Dean Howells, who was asked to evaluate the lot and suggest fixes where needed. Reviews were mixed from publication start: “Slightly disjointed” said NY Times in 1876, noting “an unnecessarily sinister tinge over the story,” its appeal to children questionable (Mark Twain had stated firmly that his book was meant for adults). Tom Sawyer would be no instant classic. In fact, it sold slow for a first several years, gaining strength after to become Mark Twain’s most popular novel, declared a “landmark” by Booth Tarkington, who wrote a rhapsodic forward for a 1922 reprinting in which he called Tom “the first full-blown boy in all fiction.” The book was by then ensconced in literary canons, what with Huckleberry Finn following, plus several more Tom Sawyer stories during Mark Twain’s lifetime. My recent reading was without rose tint and mindful that here was a thing revered, but never wholly so. Was Tom Sawyer disjointed? I thought so, and Ferguson acknowledged as much (“The story of the original is shoddy melodrama at best”). Then why did he so ridicule Selznick effort to smooth out inherent weakness? Critic reflex was to assume philistinism the outcome of any Hollywood effort. This bespoke their literacy and drew a Maginot line twixt thoughtful reviewers and celluloid peddlers who would insult a public’s intelligence.

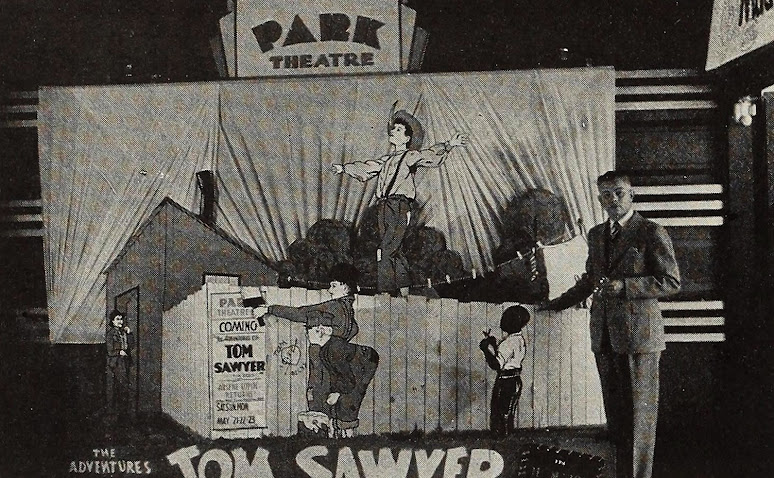

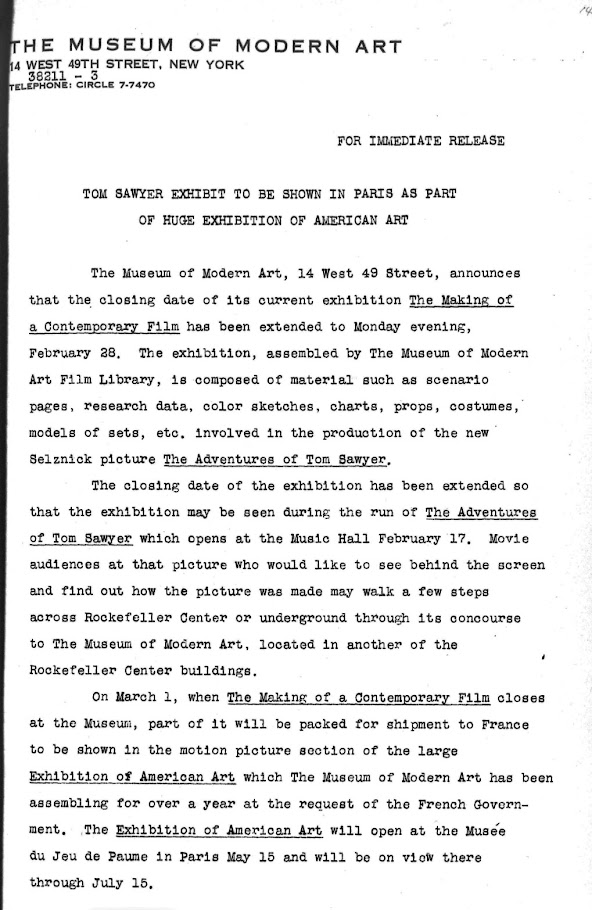

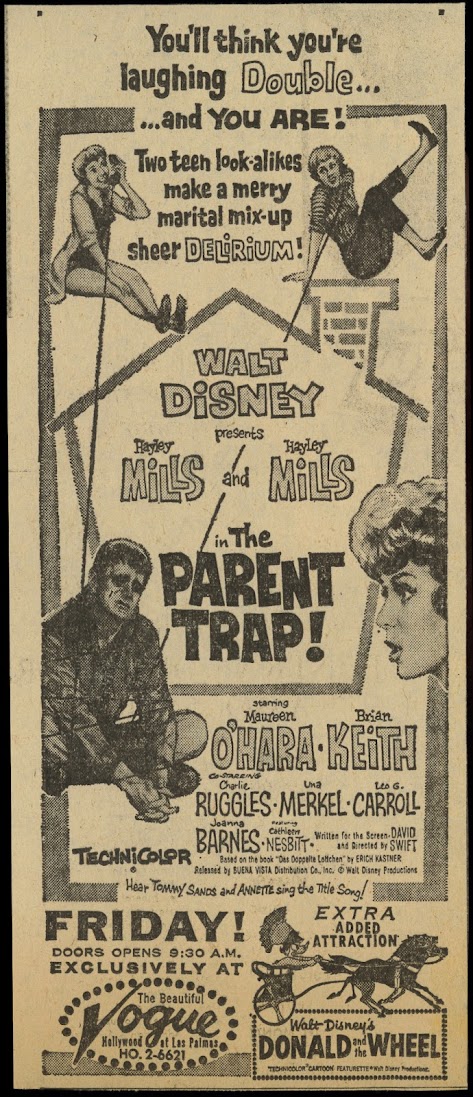

Selznick invaded cultural sanctums where he could, for Tom Sawyer instance a display at the Museum of Modern Art to demonstrate effort that went into filming a known and loved novel. Visitors could inspect among other things the memos between DOS and Code monitors wanting scenes and dialogue trimmed for public consumption. Ferguson saw the exhibit and sprang upon censor intervention as proof that films had little hope of capturing spirit of Mark Twain, or anyone that wrote freely. “Amazing resource and patience that were behind its millions of things and dollars” could not breach walls so rigidly maintained, gatekeepers’ own Maginot to separate best intentions from compromised result. It was as though any exhibit revolved around Selznick’s effort would be misplaced at MOMA, or any museum devoted to fine art. But wasn’t it Otis Ferguson who once wrote “the truth of films can be more vivid than the truth of fiction”? No critic operating outside the industry could know struggle that came with proper adaptation of a classic, or even popular, novel to altogether different medium that was movies. There would come occasion in 1941 when Ferguson got schooled, a trip to Hollywood underwritten by his employer, The New Republic, the critic invited to go behind cameras and learn what went into entertainment that by all and final necessity, had to entertain. Most impactful of time served was his with The Little Foxes, occasion for Ferguson to realize how tough a commission it was to cross gulf between a stage and screens. He would write with awe as to labor spent on a single scene, all but acknowledging what little he had understood of a complicated process (having been there to watch it being filmed). Ferguson gave The Little Foxes a rave upon release, at last appreciative of effort gone into a thing so fine. Did the awakened critic wish to revisit some of what he reviewed previous and perhaps be more generous? No opportunity alas, for he enlisted in the Merchant Marine for wartime duty and died later in a bombing raid (1943).

|

| The Museum of Modern Art's Tom Sawyer Exhibit in 1938 Ties in with the Selznick Film |

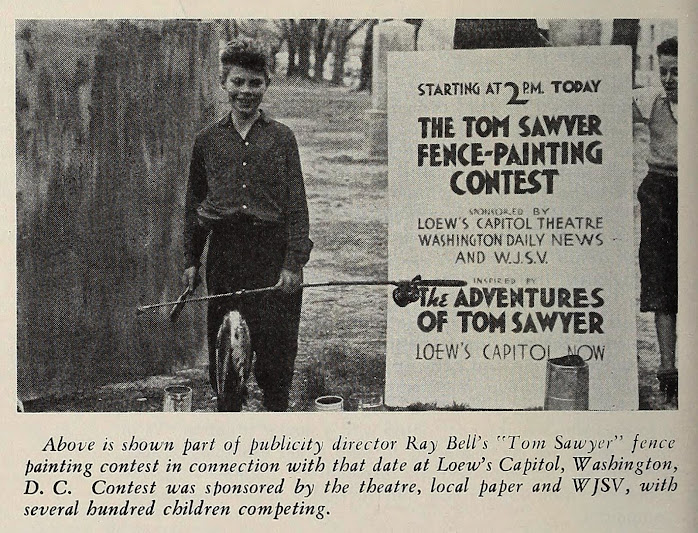

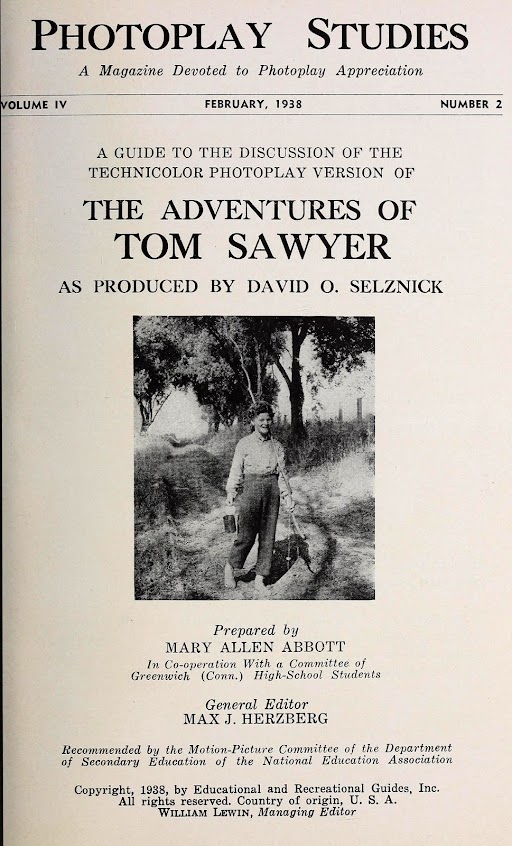

I was taken aback when a final third of Tom Sawyer the novel fell apart, or was that me being plebeian? Tom Sawyer was supposed to be an unimpeachable classic, though I doubt Selznick found it so, being too much the realist for all of regard he felt for literature. Mark Twain’s was merely another property he was obliged to improve upon, a process essential to make it palatable for 1938 audiences. Selznick knew in advance he would be criticized. Moviemakers got so little respect, wiser ones giving up any chase for it. Tom Sawyer would be hopeless if faithful-adapted, to wit: On page eight, Tom picks a fight with a boy he has never met, this a symptom of Tom being “not the model boy of the village.” Selznick knew that to open his story thusly would lose audience sympathy straightaway. Tom must be embraced if we are to spend ninety minutes with him. There is business with a “Pinch-bug” in church, and later a “tick-running.” Insects might register in a novel, but with movies, never, leastwise seldom. I’ve never seen drama or comedy revolved around a tick, nor would desire to, being discomfited just reading the tick chapter in Mark Twain’s book. Experienced screenwriters would jettison such as a matter of course. DOS had John A. Weaver on that job, with veteran Marshall Neilan to aid the treatment. Ben Hecht reportedly lent assist. What the novelist got right, they left alone. Tom at fence painting seems composed for film, so leave it intact they did. But his taking school punishment for Becky Thatcher seems labored in the book, complicated by another boy being the guilty party, so begged to be telescoped into a single scene.

Selznick knew what worked between pages would not necessarily do so where watched. I spent a couple days reading Tom Sawyer, saw the 1938 movie in an hour and a half, for which praise to the David Selznick team for measures necessarily taken. Here was thankless work seldom understood by a public and most critics less versed in art of visual representation, seeing as opposed to imagining, the literal in front of your eyes as opposed to what words conjure up. Otis Ferguson was too experienced and capable not to grasp this. Maybe he could have written a script faithful to all aspects of Tom Sawyer, rather than calling Selznick’s job “a colored-candy version” for “people (who) want a chocolate-marshmallow sundae with nuts.” These seem cheap shots. Selznick revered great books, but came to know what must be done to tame even the best of them. Changes had been made to David Copperfield which satisfied most, A Tale of Two Cities and Little Lord Fauntleroy to follow. The producer saw weakness in sources and confessed them to memos. Two Cities was “sheer melodrama” which could not effectively play “minus Dickens’ brilliant narrative passages,” the book’s “mechanics” tending otherwise “to creak.” How many had nerve to face celebrated literary works in so foursquare a manner, being not afraid to alter where needed? Selznick had to be a showman first, his medium not one best served by page-to-picture fidelity. Mark Twain dragged out Tom and Huck’s hunt for treasure and gave us subplots revolved around Injun Joe (his lethal designs upon the widow Douglas). There was no chase after Tom and Becky in the cave, Joe’s death taking place “off page” with faint dramatic impact. The author wrote friend Howells that little of this mattered, “since there is no plot to the thing” (the author in view of this resisted efforts to adapt Tom Sawyer for the stage, though unauthorized versions proliferated). It took Selznick to give Tom Sawyer structure that would work, tempo and pace to excite, and a climax to entirely satisfy.

PREVIOUSLY AT GREENBRIAR: A two-part visit to The Adventures of Tom Sawyer from September, 2006.