What If They Walk Yet Among Us?

|

| Most Noted of Literary Hauntings --- Scrooge Met by a First of Several Ghosts |

After All is Said, Do Ghosts Scare Best?

Fascination with death is rife to us all I suppose if fewer embrace it for light conversation, but let someone close depart, and for a while at least, death is Topic A. Cousin to dying is what happens after, or what if those gone aren’t really gone, and what if one or two slip back in the house after bedtime? Such was weighty concern over past centuries when lives were short, and cemeteries were fuller than populace above ground. Remember the Brontes? I don’t know how the trio wrote for constant fear of grim reaping all about them. No wonder then that ghost stories, read/told aloud, consumed voraciously by candlelight, became hugely popular especially in Victorian time of a latter-half nineteenth century, more so in England than the US, where warding off wolves or native hostility took emphasis over spooks afoot. Life expectancy being low, and indeed it was in those days (1850: 40 for men, 42 for women, barely better, 45/50, by 1900), they spent much of waking hours, and troubled sleep, in rumination over what came after it all.

Ghost stories fed that hunger, and Victorians could not get enough of them. Christmas was ideal occasion to spin gothic tales, for reason what escapes me, but no Eve, as in 12/24, was complete without pants or pantaloon scared off family and friends as they gathered to celebrate the returning dead. Every author of note or obscurity penned scary tales, as here was where surest money lay. Charles Dickens edited magazines where the Yule issue was reliably a year’s biggest seller, and if others submitted less than was needed to fill pages, he took up quill and wrote hair-raisers himself. Tradition went back before Victoria. Lord Byron shared for months a bad weather retreat with the Shelleys, Percy and Mary, where being kept indoors inspired the trio to write ghost stories and unnerve one another for recreation (Frankenstein the result from Mary). Sicker idea of fun dated to a seventeenth century where crowds turned out, with refreshment, to watch public dissections, “corpse cutting” as it was colorfully called. And they thought ancient Rome was barbaric for coliseum excesses … seeing innards removed, limbs sawed, delighted a public for whom gore was mother’s milk.

|

| Seventeenth-Century Cut-Ups As Rendered by Rembrandt |

Lest we judge however … for last night I watched London Hospital on Amazon, a Brit depiction of healing arts circa the early 1900’s, and you’ll need a strong stomach to enter, but why wring hands over surgery staged explicit or bodies burnt to crisps when TV has been doing this dance for years, as witness NCIS and forensic exams to require tummy distress bag alongside one’s viewing chair. I’ve developed hard bark over time with these, but what does it say of we who watch carnage so casually? Movies used to locate surgery below frame lines, what went on described but seldom shown. Horrors got more horrific by displaying brains or limbs in a jar, but shrank from same organs cut from, then lifted off, live or dead bodies. You knew the Code was relaxing when Basil Rathbone sliced cranial matter in The Black Sleep close-up, and a following year saw The Curse of Frankenstein arrive with Peter Cushing spattered in blood as he dismembered at will. Bodies were now to be violated in view of all who would pay admission, so how was this materially different from corpse-cutting of yore?

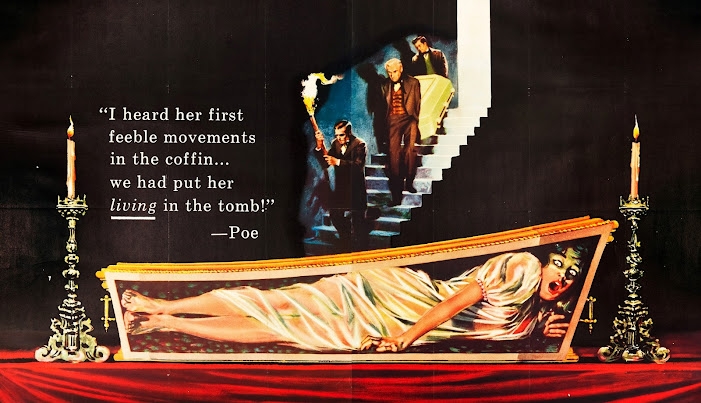

British makers applied more to such pursuit because after all, here was their folklore. The Flesh and the Fiends, a rawest so far for rifling graves with leavings dipped in acid, gave good value to chill-seekers, so much so that US distribution, hard got for Flesh/Fiends being so extreme, snuck it out as Mania or The Fiendish Ghouls after trimming butchery (plus nudity) Europe saw. Grave robbing was quite the enthrall for those morbidly disposed, as evidenced by 1945's The Body Snatcher, most successful among Val Lewton productions for RKO, mere idea of digging up the dead enough to bring customers in droves, even if the film suggested more than showed the dread act itself. Horror topics were taken up less with ghosts than mechanics of death and how those buried could yet be despoiled. American-International and director Roger Corman made cottage industry of luckless deceased being not so after all but put in graves all the same. Premature internment became dread concern, at least for those going to see House of Usher, well-named The Premature Burial, others where being declared dead was merely a start to something awfuller.

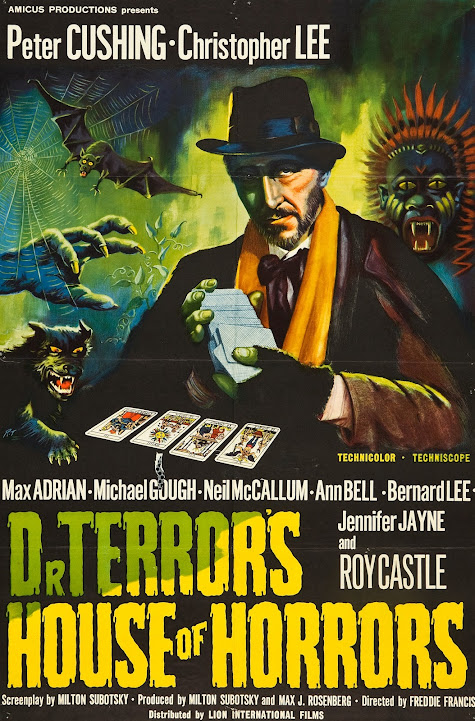

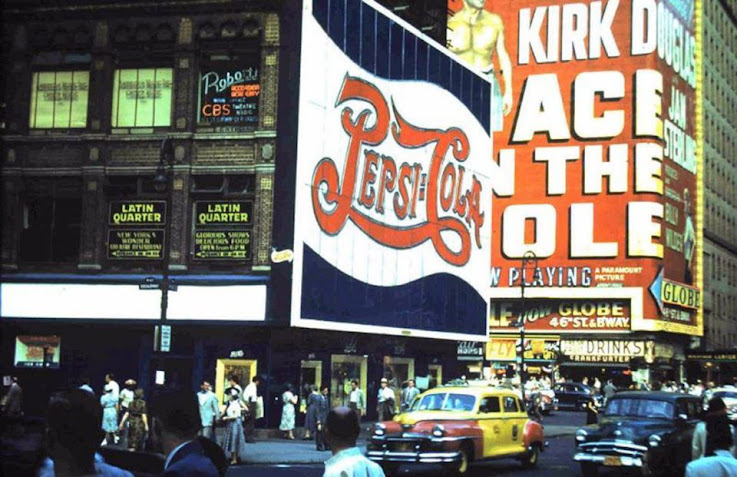

Movies centered on ghosts were rarer to come by … I could count homegrown ones in the 60’s on half of fingers … The Innocents, The Haunting, both shot in England if financed by US firms. Hammer, Brit-based, gave us vampires (not dead, but undead), werewolves (not dead but ought to be for everyone’s benefit), and modern-dress psychos seen as scarier than any ghost could be. I wanted more manifestations than films, certainly those American-made, allowed me. Even House on Haunted Hill withheld those back-from-the-dead, for weren’t scares stage-managed by sinister “Frederick Loren” (Vincent Price)? Omnibus grab bags were as stingy --- you’d think Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors would use honest ghosts rather than voodoo, omnivorous plants, yet more vampires, a hand chopped off but vindictive all the same. Got to where it seemed ghosts were no one’s cup of tea but mine. I thought it likelier I’d see a real spook than go to outer space someday, which was why science-fiction appealed to me less than gothic horror. Went with a cousin and his friend from high school to see 2001: A Space Odyssey in 1968, playing in “Ultra-Vision” at the newly remodeled Winston Theatre, an hour’s hop from home, such event made worthy because 2001 merited such a drive, only I was too young to divine its greatness, yearning instead to return two days later for a Saturday kid show with House of Usher the screen offering along with Bingo for all and a teen band. Happenings in the horrors seemed more within the realm of possibility than inter-galactic exploration --- who knew but what I might be buried alive someday, House of Usher possibly instruct for avoiding such catastrophe.

Movies were as doubtful about ghosts as a general population was presumed to be. Frankenstein’s monster had life cobbled from corpses, The Mummy rose thanks to incantations, never of his own volition. Neither were ghosts per se. Where were simple spooks as Victorians had in short stories? Tales got told in infinite number once Americans embraced the literary genre, but Englanders did it more and undoubtedly best. Analysts tried to explain why a latter half of the nineteenth century was so spirit-filled. Candles were understood to be ideal accompany to spinning of scares, then gaslight came along and, while it lighted rooms better, gave off carbon monoxide to cause hallucinations, these making readers/tellers think ghosts indeed were real. Photography had caught on and it was realized that the dead could be captured by lens, not actually so, but the nature of slow-timed exposures left all type of odd imagery on finished photos, and some swore departed had come back to pose. Low-priced magazines were the rage, hundreds of them plus newspapers with appetite for short stories never satisfied. Writers could live off the thrill trade, then anthologize backlog and sell output all over again. Publishers topped rivals with one compilation after another, thickness past a thousand pages with seventy or more entries, “A Century of Creepy Stories” (1930) typical of collections to burn anyone’s wick down to the wax.

|

| Stage Spooks On The Loose Plus The Body Snatcher As Screen Sensation |

An advantage literature had was ghosts we could imagine rather than face head-on. We'd form our own image of the returning dead rather than let a camera fake one for us. Film was where there was no doubt you were looking at someone else’s special effect, and how often do screen ghosts fit an individual’s concept of same? There is something personal to that, for which no substitutes will do. I like the ghost we finally see in The Uninvited, knowing the while that others may laugh. Being told there is no such thing since babyhood is a signal, more a command, to chortle when specters show up. The very word “spook” cues us to smile, this why parents felt safe letting offspring attend “Spook Shows” during latter’s stage vogue. Maybe ghosts were better left to print than pictures. Victorian-era magazines graduating to illustration of stories saw readers complain that the unseen now shown was a let down from what imagination had supplied. For every movie that depicted ghosts, there were a thousand previous and present told tales doing the same, at safe distance of written word that required us to supply imagery.

Best then to invite laughter where venturing to graveyards. Laurel and Hardy did it in Habeas Corpus (1928). Hired to snatch content from a cemetery, they go there and are properly terrified, apt response for Habeas Corpus being shot in darkness and L&H paid to dig up remains and intent on doing so. Lighter treatment was The Live Ghost (1934), where the boys are shanghaied aboard a haunted ship, a drunk immersed in whitewash assumed to be a ghost, fun had due to varied misunderstandings. War brought ghosts closer to home and hearths, their presence welcome and encouraged. A father who has passed moves among his family to lend comfort when a son is lost to combat in The Human Comedy (1943), and Spencer Tracy stays around after death to pave way for fiancée Irene Dunne and Van Johnson in A Guy Named Joe (1944). Ghosts often had unfinished business with mortals, a crime to be unraveled, murder of the deceased or betrayal of some sort, this an oft-device of stories past and ongoing.

The Uninvited (1944) had competing ghosts sorting out dread events that led to respective deaths, and it is for the living to separate benign from malign participants. Dead of Night (1946) told at least one ghost story of five, a little boy who was killed long before but appears to Sally Ann Howes during a Christmas gather. Here was a beautifully evocative couple of reels within whole of an omnibus to come closest to what Victorians achieved with their short tales. Maybe a best of American creators doing a similar thing was Val Lewton with The Curse of the Cat People and its life-affirming depiction of spectral presence, here being a ghost that helps. What would be labeled as comedy for Abbott and Costello in 1946 was near-profound meditation on disturbance that compels the dead to come back and fix history that is broken. The Time of Their Lives was Universal set upon rebranding A&C, to freshen a formula wearing out boxoffice welcome. Little Giant (1946) had split the team for much of running time, The Time of Their Lives going a next mile by period-dressing them for a first couple reels, then denying the team interaction by letting Costello be a ghost that Abbott cannot see. Result was a favorite of all A&C but for those who’d stand fast beside Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein.

|

| Note Posters Above Play Down Actual Content of The Time of Their Lives |

Concept of Lou and ghost-mate Marjorie Reynolds righting a wrong from 160 years before raises The Time of Their Lives above mere haunting gags to dignify these ghosts with an urgent mission, prelude to main narrative seeing them both shot down and thrown in a well, cursed to remain on the estate where they died. Latter is surprisingly grim, so we want the restless spirits to be vindicated. The Time of Their Lives was one of few times A&C had a story with real stakes and complication. I’d like to think the team respected it enough to put best feet forward. Abbott during the Revolutionary War portion is a straightforward heavy, Costello’s death an indirect result of his treachery. The Time of Their Lives hews close to tradition observed by Victorian writers, the ghosts not disposed to rest until their long departed names are cleared, this an Abbott and Costello for people who ordinarily would not watch Abbott and Costello. I once set an alarm for one am so I could see it on Channel 2-Greensboro, satisfied that missing the broadcast meant never having such opportunity again. Now of course there is a Blu-ray, along with all the other Universal A&C’s, from Shout.

Honest ghost stories were rare on film and to be savored. We saw a rarity at one of the Syracuse shows, referred to as the Orson Welles Ghost Story, actual title Return to Glennascaul, a short subject written-directed by partners in Welles’ Othello project, and released to theatres in 1953. There were playdates, if not many, and the film was nominated for an Academy Award as Best Short Subject. Fans want to claim it for Welles because he appears and narrates, but that appears to have been the extent of his participation. Return to Glennascaul tells a subdued and effective ghost story, was shot in Ireland on spooky roads pointed to bleak houses. The ghosts are benign but not quite to be trusted. The tale takes as long to unfold as we’d spend reading a short story, which is why in part it works so well. Highpoint of creeps is when the traveler realizes he was a guest of ghosts. So many stories work best when they aim no higher than that, atmosphere and suggestion preferred over pyrotechnics or spooks too belligerent. I wish Welles or someone had sponsored a whole series of these, Return to Glennascaul the one/only pearl an extra with Criterion’s Blu-Ray of Othello.

|

| Karloff Invites Us To Chat With Ghosts in Black Sabbath |

Ghosts seemed more to comport on stages than screens. Those “Spook Shows” traveled far/wide to theatres large/small. None of what they did was meant truly to frighten, though some tickled edges via “beheadings,” sometimes of audience volunteers, and bloodshed made to look real thanks to sleight-of-hand adroitly applied (most spookmeisters were variety inclined magicians). Attendees could ask why real ghosts cared to tramp about a theatre crowded with children, and who believed for a moment that James Dean would permit himself to be “materialized” by a ghoulish master-of-ceremonies? That last might latterly be seen as shockingly bad taste, but stars who died untimely were assumed to itch for whatever incantation might usher them back, especially where invited by black-clad “Vampira,” a Dean girlfriend (she claimed) interacting with him more in death than when he was among us. Serious treatment of ghosts by movies remained a higher hill to climb. Fox didn’t want The Innocents used for Saturday spook fests, and so sold it as rarefied object beyond risk of snickers or derision, maybe not so keen an idea as it would lose money for them. Euros as always understood the returned dead better and so offered Castle of Blood, Black Sabbath, others of disrespected-by-a-mainstream category. Karloff for Sabbath introduced a trio of phantoms by asking us frankly, Do you believe in ghosts? Most with the quarter to get in were expected to reply yes, while parents stayed home. Latter had long since given ghosts the gate, even ones pitched to their level like The Innocents, or later The Haunting, which also went in the red, this time by nearly half a million. Ghosts then were the province of youngsters or fools, at least by movie measure. That would change as appetite for supernatural content became insatiable with streaming’s arrive and domination it would achieve. Now it is The Haunting remade as a series plus Turn of the Screw/The Innocents (as Bly Manor) that invite us to binge on ghosts. You could argue that, thanks to Netflix, Amazon, the rest, ghosts have never had it so lush.