Film Noir #22

Noir: Chicago Confidential and Chinatown

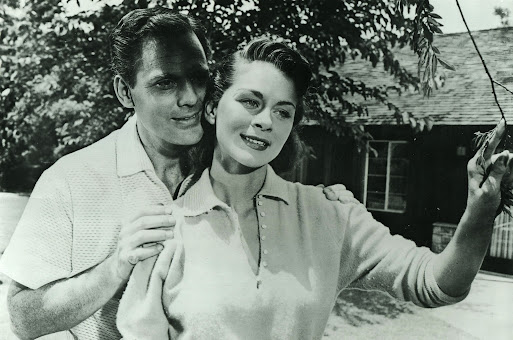

CHICAGO CONFIDENTIAL (1957) --- Posters say “It Rips Through “Chi” Like a Hurricane,” but really it doesn’t, being cautious look at labor unions incorruptible except when outside racketeers muscle in. Corruption as everyday habit of brotherhoods was hands-off as in no such hint from a film industry very much close shopped by 1957. Whatever headlines from real life, there was no blaming union policy or leadership for any acts that might or should be prosecuted, leaving villainy to dog heavies (unbilled Jack Lambert) or long-in-tooth holdovers from the Capone era (Gavin Gordon as Mister Big). Compare Chicago Confidential with Scorsese’s The Irishman and hand yourself a laugh. Still this modest one is fun so long as expectation lays low, Chicago Confidential close as 1957 got to a B by once-definition. Brian Keith has his first starring role as State’s Attorney who is all-upright, and we could wonder how crime had any chance when civil authority is bleached so clean, especially where it’s Chicago we’re dealing with. Union head Dick Foran is object of a murder frame, subordinate Douglas Kennedy the bad apple who has wormed into Dick’s otherwise pristine labor group.

Where “waterfront derelict” Elisha Cook, Jr. is key witness for the prosecution, you’ve got to figure something fishy. It’s for Keith with help Beverly Garland to find new evidence that will spring Foran from the death house, key break courtesy “Ryder Sound Research,” real-life entity we see in old film credits, here rescuing wrongly accused by separating “alpha” and “beta” signals from recording of a human voice. Technology serves as restorer of lost hope as in Call Northside 777, White Heat among exhibits for tools presumed to be out of crime’s reach. With such resource at enforcement command, where’s worry for any innocent party? Hitchcock had sternly answered that question but a year before with The Wrong Man, his stance that chance alone might rescue the wrongly accused, accent on “chance” translating to hundred against one in favor of the rope.

CHINATOWN (1974) --- There was real life noir behind these cameras … Roman Polanski directing, and he can’t even enter the country anymore (warrants waiting), plus Robert Evans as producer, and what sleazy outcome awaited him (best not to read “final days” account). Evans and screenwriter Robert Towne tangled, along with J. Nicholson, on a sequel in 1990 that went sort of wrong, The Two Jakes, a magazine story detailing “very public collapse” of the project, this five years before the movie got released, but I’ll save The Two Jakes until it comes up among T's (when … in 2040?). For meantime, there is Chinatown, a picture much better to mine eyes than in 1974 being still young to grasp subtleties or understand truly what was going on. Seeing Chinatown at a drive-in first was bungle for which I should have had my moviegoing license revoked. Chinatown belongs to still and quiet of dark space, walls, ceiling, and a wide screen. It and Barry Lyndon work period spells better than anything I know from the seventies. If there is old-style noir as rendered thirty years late, this am it. Yet some are discomfited by Chinatown, lots because of tie-up explain re Noah Cross (John Huston), his daughter (Faye Dunaway), and “granddaughter.” It is shocking still, so imagine how it connected in 1974, but then Oedipus shocked them plenty too, and that was thousands of years ago. Billy Crystal hosted the Oscars one 90’s year and gagged up Chinatown’s showdown scene between Nicholson and Dunaway, him slapping and her crying She’s my sister, She’s my daughter. Billy’s joke fell flat because no one in the audience got the reference. He stood looking at blank faces and said, Rent the video. That’s how quickly they forget, even in Hollywood, especially in Hollywood. Chinatown was popular enough in 1974 to make it seem for a while as if pictures like this might come back, as in disciplined and classically structured. The screenplay by Robert Towne was “taught” by writing gurus for years to come … is it still?

The story of how Chinatown (barely) got made is another to illustrate the miracle of any great movie seeing light, especially in the seventies when lifestyle and habits were so appalling that it’s a wonder creators lived into the eighties, let alone to now (many of course did not). Reading Chinatown’s backstory and fate for participants is dark walk. Still, the picture speaks for them, and did, I think, redefine noir as that language would be spoke after. Good as it was, Farewell My Lovely of a following year seems quaint by comparison, an old movie done new, but stuck still in mindset of old. Chinatown seized relevance by centering its story on evil doings that really happened, water as most valued resource and worth killing to get. There are books on this topic, and I bet they are scary too. Was Noah Cross right when he said given the right time or circumstance, people are capable of anything? And how many less old buildings are left in L.A. than in 1974? Seems I read they had problems locating authentic surviving spots when 1990 time came to do The Two Jakes. Reminds me of when we drove through Culver City looking for where Laurel and Hardy shot shorts, precious few recognizable places found. Vanished sites of Los Angeles is such bittersweet aspect of film noir, be it buildings and housing used for Chinatown, or long-gone Bunker Hill that enlivened features from after the war and into the sixties. Easy to lament loss of all this when you see what took its place. You Tube explains via melancholy tours uploaded there.

ANOTHER FORGET: Checking Greenbriar index site just now and discovered a column from 2015 about Chicago Confidential. Doesn't overlap much, so HERE it is for CC second helping.