Music for Hopefully Millions

|

| She was Twitchy, Him Tormented, and Twirl Went Turnstiles for Columbia with A Song to Remember |

Could Classical Come Back?

To collect silent movies was to find music that would accompany them. This didn’t occur to most of us age ten and watching Castle reels of Dracula, or The Lost World, those but glimpse of something it seemed we’d never own complete. Same with Woodpecker cartoons or Pluto caught on flypaper. I knew graduation to two-reel and intact subjects carried with it duty to supply sound for twenty minutes a Chaplin or Laurel and Hardy would last. Would I have applied myself more to piano lessons for realizing how handy they’d be to furnish accompany? The connection didn’t occur to me, so past went opportunity to learn a skill at the least useful for anyone who'd supply live in addition to screen entertainment. A phonograph made do, selections not ideal to all action projected, just now-and-then harmony between picture and sound. For a first several years I’d choose Chopin ... piano, not his concertos. I became a fan and would listen to him even without the films. Among “electives” at college was an appreciation course I was predisposed to enroll in, “The Enjoyment of Music,” among few keeper textbooks. The instructor was a lady who grew up in the forties and took a dim view of how Hollywood treated classical composers, being derisive toward A Song to Remember, the Chopin story as told by Columbia Pictures in 1945 wherein the suffering genius “spat bright red blood all over the piano keys,” a scene she called laughable for showing how movies always got true-based stories wrong.

|

| Hep Ahead of Her Time Merle Wears Man Suits and Writes With a Green Feather --- I'm in Love! |

Goal became to see A Song to Remember, more dreamt of than done when Columbia TV packages seemed limited to 50’s titles and lone earlier outliers like Sahara or Dead Reckoning. I contented myself with stills and a horse-blanket sized pressbook to confirm A Song to Remember as a dynamo of its day. There even was a soundtrack album when those were 78 RPM’s in a treasure box to keep till big broom 33 LP swept cruder formats away. A Song to Remember was an experience its initial audience would not forget, a lift to Columbia followed up to even greater success with The Jolson Story, a then-cousin to Chopin for making old new again. Popularizing a classical composer had barely been done, certainly not to extent of Chopin here, MGM’s The Great Waltz of years before a noble but less lucrative try, its Strauss story an alright earner but cost-heavy as to see ultimate red, happy coda come 1946 when Leo, fired by rival success with A Song to Remember, reissued The Great Waltz to more than make up shortfall of before, such being reach of hit parading Chopin. Something about him spoke loud to kids and romantics, for how else do we account for his melody informing sock hit theme of Till the End of Time, disc coverers to include Perry Como among numerous others. Chopin in short became hot again and helped by Cornel Wilde playing him, teamed with gender-bending Merle Oberon in tailored suits to become a mid-forties fashion influence.

|

| Bob Ripley Might Say "Believe It of Not" to This Assemblage of Song Endorsers |

Technicolor brightened costume setting with style its own revolutionary, most noted a scene where Oberon enters a dark room with a candelabra to reveal Wilde as Chopin performing (salon-goers think it’s Franz Liszt), a moment to forecast what Stanley Kubrick would decades later do with color and candlelight in Barry Lyndon. Song’s entire score was based on Chopin, reminding us how fit a utility he’d been and would continue to be for movies. There was something fresh if not eternal about this composer’s work, not music you’d have to “adjust” the audience to. Just start it up and stand back. Billed first for Song was Paul Muni playing his eccentric teacher-mentor after Yiddish theatre example, Muni’s own training ground. Lots say, and said in 1945, that he chewed scenes to powder, left no room for colleagues, which they’d complain of later. Nina Foch recalled Muni as “old-fashioned,” while Cornel Wilde found him insufferable, the older man off in his own world with no seeming recognition of partners in his actor orbit. It was Muni and nobody else so far as he saw it. Knowing Foch since she was a kid, Muni was friends with her father, so on the first day asked her, Do you want to be an actress or a whore? WTF she undoubtedly thought, figuring the shoot for an ordeal to come. I’ll guess Muni merely inquired in his singular way whether she’d apply herself to the art/craft or merely pull an ingenue plow. Being with Columbia threatened her plenty with that, Song but her second job after Return of the Vampire, abashing to her at the time. Any of us could have assured Nina that effort alongside Bela Lugosi was in fact an early summit.

|

| "Song-Drenched Kisses" and "Champagne Love" --- Were These What Put Over Great Waltz Reissues? |

|

| Poor Schumann Was Sort of a Mad Genius, But Not Homicidally So |

Was Frederic Chopin a Polish freedom fighter? He seems so here, not with guns aimed at Russian oppressors, though he does attend a secret meeting of rebels before massacre of same obliges him to decamp to Paris where remainder of narrative more/less takes place. This seems contrived even though Chopin was a booster for Polish rights and did compose music to support the cause, but we’re for the piano bench here, not Chopin ducking czarists. Writers may not have recognized early on that Chopin’s music would be plenty enough to sell this show. Merle Oberon as George Sand speaks for us where telling Frederic that he’s wasting time and energy trying to liberate a homeland when talent lies so spectacularly elsewhere. Oberon is meant to be pushy and dominating but like with so many film devices that try to manipulate my sympathies, I in fact sit firm in her corner, especially for fiery D/C/S speech to Wilde/Chopin (D/C/S meaning Davis/Crawford/Stanwyck). Of what I’ve read about A Song to Remember, few address the concert and performance scenes, which of course is bulk of what we wanted then and now to see. Pianos Chopin plays are the best of the best on 1945 terms, which means as good if not better than what we have today, but A Song to Remember took place during the lifetime of Frederic Chopin, which was from 1810 to 1849. According to Deems Taylor in a very informed essay he wrote decades ago (included in a compilation volume, Of Men and Music), instruments were throughout most of the nineteenth century inadequate to convey intent of composers, so give up hope of satisfactory time travel to concerts when classical was new.

|

| Catherine McLeod Puts Over, and How, Keyboard Work for I've Always Loved You |

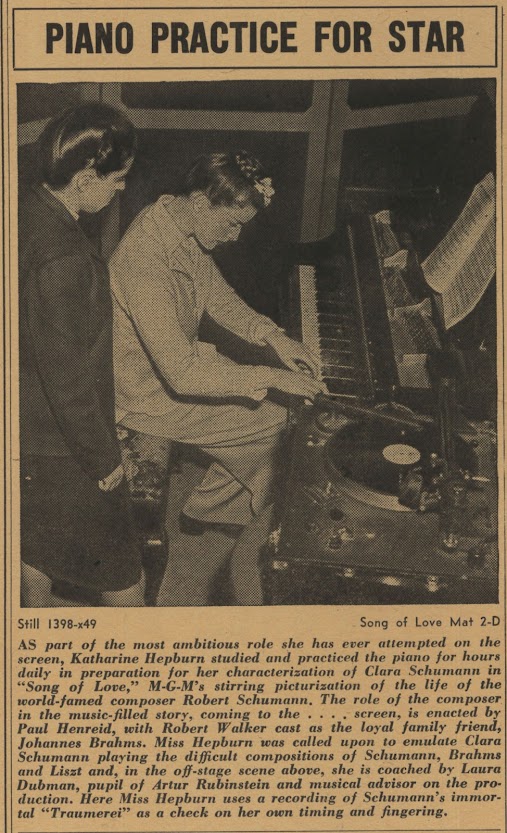

Chopin at his piano, or piano forte as it was then known, saw sky-high talent brought cruelly to earth each time he sat to perform. What was put on paper was brilliant --- as translated by instruments then-available, it was something else. Taylor wrote: “The piano upon which we now play … is not the clavichord or so-called pianoforte for which … composers had to write. That was an evolutionary instrument, halfway between the harpsichord, with its jacks and quills, and the modern piano. It did possess a rudimentary dynamic range --- its very name, pianoforte, is the perpetuated boast of its inventor that it could play both soft and loud; but its tone was a pale, characterless tinkle, compared with the singing thunders of a modern grand piano.” Reality of recitals amount to cold splash for those who’d imagine Chopin or any of contemporaries mesmerizing listeners of their era, Taylor asserting that “up to the very third quarter of the nineteenth century, a composer not only had to struggle to get his ideas down on paper but then had to worry about getting a decent performance.” Chopin was gone a generation before his century’s final third. Same was case for his contemporaries Robert and Clara Schumann, memorialized by Metro in 1947’s Song of Love, a screen bio hoping to duplicate Columbia’s success with A Song to Remember. Toward this end they’d fail for $2.6 million spent on the negative with result a million lost. Romance Leo hoped to celebrate was essayed by Katharine Hepburn (Clara) and Paul Henreid (Robert), with Robert Walker as Johannes Brahms, who according to history did spend most of his life in hopeless love with Clara. This might have clinched receipts had casting been different … not that anyone was inadequate, just sparks lacking where Cornel Wilde and Merle Oberon had them on Chopin behalf. Speaking to authenticity, Song of Love and A Song to Remember saw mutual casts sat before keys and obliged to finger in close tandem with music played, each more-less doing the Larry Parks thing only with pianos rather than voice. I look at Wilde or Hepburn hands sailing keyboards and wonder how the stars would sound if left to own devices rather than being dubbed. History records that of Song of Love principals, each of three could play, Hepburn so accomplished that an idea was floated to let us hear her rather than a pro dubber, but studio feet got cold, and besides, they had already paid for the do-over.

|

| Hail Hail, the Classical Gang's All Here for Carnegie Hall |

MGM doesn’t get enough credit for enriching 40’s patronage. Look, or better listen, to Music for Millions, Song of Russia, or any of Kathryn Grayson or Jane Powell vehicles. Even some of the Tom and Jerrys. Stay into fifties and witness Rhapsody, now obscure perhaps but noticed and appreciated then. Take a hundred youth into any of these and who knows but what five, ten, maybe more, will come out tilted toward great music. This was servicing a big tent, and not just Metro was masterful at it. Any classical banquet screen-served, in whatever its size and majesty, had first to serve a story, be but handmaiden to melodrama its true, this needed to engage an audience not content with mere recital of music, however distinguished. Classics could be and were route to prestige for even Republic Pictures, set upon doing what Columbia with A Song to Remember had profitably done. I’ve Always Loved You was their two million investment toward industry standing not so far achieved with westerns and serials, Technicolor from Republic also unaccustomed. Love and its frustration was necessary backdrop to recital of Rachmaninoff, Mozart, Wagner, and yes, Chopin, plus others of classic repertoire. I could talk of production and reception the day through and come nowhere near exhaustive coverage by Jack Mathis in Republic Confidential, his multi-volume history in which “The Studio” addressed I’ve Always Loved You in stunning detail. No way could Mathis’ effort be bettered by me or anybody. I’ve Always Loved You was released on Blu-Ray by Olive, theirs derived from the UCLA restoration of a feature more-less unseen for decades. It’s a stunner of a celebration of all things classical, as is …

|

| Shot Right Where It Happened by Edgar Ulmer, Who Sure Knew from Classics (Remember The Black Cat?) |

… Carnegie Hall from 1947 and another difficult find for years prior to DVD and occasional runs on TCM. Here was closest we commercially got to a concert feature long before such things became norm, yet like others Carnegie Hall had to serve audience need for narrative, being a family saga set inside the legendary Hall where the film was in large part shot. Carnegie Hall enjoyed long urban runs, set a record for electric lights to herald initial play at the Winter Garden in New York. As expected there were purist complaints of soppy drama getting in way of all-star classical performing, but how could 144 minutes pass if not with help of romance and mother sacrifice for sake of a son who chooses swing rather than symphonic? Issue is resolved by letting him have it both ways, thus Vaughn Monroe and His Orchestra and later Harry James cutting rugs alongside expected longhair artists. Producing Carnegie Hall was Boris Morros and William LeBaron, both with seasoned sense of how to best put over porridge of old with new. Concert stars, plus those from opera and cultivated elsewhere, would be humanized by interacting with story enactors Marsha Hunt, William Prince, Frank McHugh, and Martha O’Driscoll, all this shrewdly managed by director Edgar Ulmer, whose only lavish film this was. For splendid work here, why wasn’t Ulmer finally promoted to A features upon artistic and commercial wings of Carnegie Hall? It would earn domestic rentals of $983K, with foreign an additional $607K for distributor United Artists. Known well was Ulmer being blacklisted for conduct unbecoming an employee at Universal during the thirties (him purloining a wife from a U executive). The Ulmer marriage sustained so maybe career spank, a harsh one, was worth it. As is, and thanks in large part to Ulmer, Carnegie Hall represents apotheosis of classical celebration in otherwise contemporary and commercial focused medium that was movies.

UPDATE --- 7/29/2025: As we know, one of the greats among writer-historians is William M. Drew. Recent e-mails from William address Greenbriar's 7/14/2025 column about "voiceless" stars I thought we'd never hear. Not so for all, says Mr. Drew, and he supplies links (inc. Mary Miles Minter!). So much detail here I had to break it down to three parts to fit Google limits. Need I add, terrific stuff.

9 Comments:

Disney dabbled in the classics outside of "Fantasia". "Sleeping Beauty" based its score on Tchaikovsky, and Greenbriar has reported on the Disneyland hour that included a half-hour bio of the composer, narrated by Paul Frees and designed to imply his whole life was building up to composing a ballet that Disney would adapt.

"The Magnificent Rebel" was a two-parter on Beethoven for "World of Color", and interestingly was issued as a Disney Movie Club DVD in that format (two hour episodes with original credits and Uncle Walt introducing) instead of the overseas movie version favored for video release. Part one has him as the brilliant, irritable student whose career is just beginning as his noble girlfriend's father breaks their engagement. Part two picks up when, at the seeming height of his success, Beethoven loses his hearing and his spirit until religion and nature lead to a comeback. Shot on location, it looks handsome and occasionally lavish.

"The Waltz King" is far less epic that "The Great Waltz", but with a lavish look thanks to real Vienna ballrooms and theaters. History is again stripped down and cleaned up: Johann Strauss Jr. and Sr. are, ahistorically, monogamous. There's a lot about the pains of being the equivalent of a rock star, being assailed by beautiful girls in ball gowns and getting tired of playing his hits. This DVD is in movie form, although it obviously breaks into two free-standing stories.

"Almost Angels" is about the Vienna Boys Choir, and is beloved by some. I remember it from television and at a young age thought there was something weird about one's voice changing presented as a terrible tragedy.

Recall catching half of "Ballerina", a "World of Color" two-parter about a promising dancer choosing between a demanding career and the nice boyfriend. It was very much about the nuts and bolts of a modern European ballet company, emphasizing the hard work.

A SONG TO REMEMBER popped up on local TV with surprising regularity when I was growing up in the 60's. The one piece of the composer's work I would instantly recognize and love, of course, was Chopin's Etude Op. 10, No. 3. This was the bittersweet theme used (okay, OVER-used) in all those Robert Youngson silent comedy compilations! Still makes me think of Harry Langdon, Laurel & Hardy et al.

Donald, right you are to credit Walt Disney with popularizing classical music, from his 30's cartoons (The Band Concert noteworthy) right through Fantasia, sections of his omnibus animated features, plus all of things you mentioned from the 50's and into the 60's. Did ever any producer contribute so much to the classical cause?

One good thing about using classical music in film in the 30s-60's was that it was free.

Classical music was all over in the 40s in a way that it is impossible to imagine in today's environment with radio stations constantly having live performances of them and operas on AM stations up until the 90s when they began to vanish from the eter. At least that was my own experience in Argentina where to point somehow a part of the country did not fully embrace neither the 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s. All these movies involving classical music composers always played on TV where they felt unremarkable and not as popular as the music itself, even in the 80s when their popularity began to wane. In Massachusetts after my father's passing, I began listening to the classical music radio station in Boston as a sort of informal homage to him... but after three months, I realized that there was no variety in the selection and that they were always rotating the same "popular" pieces over and over again to the point that I have to change the station never to return. I never liked any of the movies or miniseries involving classical music composers because I always feel that something is not right in them considering that the events took place like 200 years before there was any film camera. But I do love DONDE MUEREN LAS PALABRAS, the first film directed by Hugo Fregonese, where you can listen to Beethoven's 7th symphony complete. It is a much better film than another one that came later in the same vein, and here it is in two versions:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jpZOPRhwGAM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K6qyi_lxEIo

Disney got as far as two installments in his "Adventures in Music" series, both toe-dipping into 1950s cinema gimmicks: "Toot Whistle Plunk and Boom" is widescreen, "Melody" is 3D, and both toy with UPA ideas. Neither features specific classical works, but to an extent they're ABOUT classical and other forms.

At the outset all cartoon producers were reliant on public domain classics, plus whatever in-house composers could create on deadline. Some had access to a studio's catalog (and maybe orders to plug songs from same), but independent Disney rarely used existing pop in his short subjects (There was RKO's "The Carioca" in "Cock of the Walk"; were there others?). At first this would have been purely a matter of money, but knowing Disney's resolve to own his productions it may have been an official policy to keep "rented" music off their soundtracks.

The omnibus features are mainly original modern music, but they do include "Peter and the Wolf", a jazzy "Flight of the Bumblebee", and "Willie the Operatic Whale" with its parody opera style and medley of Willie in classical roles.

You used Chopin to Chaplin and Keaton!?!

I have to try that now just for fun. I always used 1910s, 1920s jazz. I later learned Keaton had syncopated jazz bands on set.

A favorite cliche in movie bios in general: The hero has a short exchange with a stranger. An excited friend comes up and gushes, "Do you know who that was? That was [historic figure]!" I think it figures in "Magic Fire", which name-dropped famous people and titles of Wagner's works enough to make a drinking game.

Dan Mercer appreciates CARNEGIE HALL:

I've long been puzzled why Edgar G. Ulmer was for so long consigned to the wasteland of Poverty Row. That indiscretion of his aside, Hollywood has long been a place of forgive and forget, where talent is concerned. And certainly Ulmer was talented. "The Black Cat" was the commercial hit of the year for Universal, made within budget but rich in visuals and content, and a minor masterpiece as well, though in my more expansive moments, I leave out the adjective. Even for the likes of PRC, he created small miracles with inadequate budgets, absurdly short shooting schedules, and actors of marginal ability. Besides, the Laemmles were gone within a couple of years of his marriage, enough time, you would think, to allow other studios and producers to look after their own interests.

"Carnegie Hall" displays his masterful touch, with its majestic tracking shots and striking visual compositions, and with the highlighting of the architectural details of the recently renovated auditorium, and these were achieved within Carnegie Hall itself and not on a Hollywood sound stage. For example, the sequence where Gregor Piatigorsky plays an arrangement of Saint-Saen's "The Swan" for cello and harps is as lovely to watch, with its arrangement of light and shadow, as to listen to. There is a marvelous shot from a low angle of Stokowski conducting, his mane of white hair a halo before the celebrated circles of light on the ceiling. The technical difficulties must have been challenging, thus the accomplishment all the more rewarding.

I would have preferred that it was a pure concert film, if that had been commercially possible then, as the sketch version of "The Jazz Singer" appended to it adds little in the way of entertainment. The interludes where the musical talent mingles with the fictional characters are variable, from true and affecting as Walter Damrosch reminisces with the "Nora Ryan" of Marsha Hunt about the opening of the venue many years before, to banal and unnecessary, as when Jascha Heifetz stalks off the stage after the first movement of the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto but pauses to have a few words with her. It was only the first movement, however, and he's gone as if to say, "Th-th-that's All Folks!" Possibly these exchanges were meant to be humanizing, but it should be no more necessary for these artists than for the gods of Olympus.

What makes the film a special pleasure is the record it provides some of the greats of the musical world then at the height of their powers. Heifetz in particular displays superb technique and an astonishingly fast tempo. There is also Arthur Rubinstein with magisterial performance of the Chopin "Polonaise." If I had my way, I would cut out the narrative portion entirely and provide a new structure introducing the musical pieces and the artists performing them, and the wonders of the glorious hall itself.

Calling Deems Taylor, anyone?

Post a Comment

<< Home